Bidding farewell to the heyday of whopping returns, rampant risks

Liu Xin, an individual investor, has been twice lucky in putting money into wealth management products recommended by his banker. Both times, he was duly paid interest and principal at the promised rate, in the time specified.

But will he be so lucky going forward as Chinese regulators begin tightening the screws on asset management?

“The wealth management product I invested in was very popular,” he said.

It had a minimum investment requirement of 1 million yuan (US$153,250) and promised an annualized return of 6 percent for a product maturing in 90 days. That compares with a benchmark one-year deposit interest rate that has been cut by the central bank down to as low as 1.5 percent.

The investment products were recommended to Liu by his client manager at Ping An Bank, a mid-cap joint-stake commercial lender.

“We have known each other for a long time and I trust her implicitly,” Liu said of the manager. “So I didn’t ask for too much detail on the investment.”

Chinese regulators are moving to tighten regulation and monitoring of asset management products to address problems that have arisen in the sector in the past few years.

In November, the People’s Bank of China drafted a “consultation paper” prohibiting managers in the 60 trillion yuan asset management market from promising investors a guaranteed rate of return. It stipulates that financial institutions must instead offer yields based on the net asset value of the products they are selling.

Asset management products have become very popular among the upper-middle and wealthy classes in China as a way to park money at returns much higher than those of money market funds or bank savings accounts. The runaway growth followed the first wealth management product initiated by China Everbright Bank in 2004.

During the past two years, city commercial banks have led the way in terms of the number of wealth products issued with guaranteed returns and the rate of yields.

“We Chinese tend to look for investments with high returns and little risk,” said Xu Zewei, founder and chief executive of 91 Technology Group, a Beijing-based finance service provider.

Or put another way:

“We tend to be too greedy on yields and too fearful about risks,” said Lin Wei, a financial professional and an experienced investor. “That is our nature, and it is hard to change that.”

He cited the example of one trust company that introduced an investment product in 2007 promising an annualized return of up to 20 percent, double the average for the industry.

“The return rate was so incredibly high that I worried about the potential risks,” he said, after resisting the temptation to buy the product.

Fortunately for asset managers, most investors aren’t as wary as Lin. The market has grown explosively since 2012, with security houses, funds and insurance companies jostling for business with banks.

As the size of the sector expands, so too the risks, said Zhao Qing, a senior researcher at the Suning Financial Research Institute.

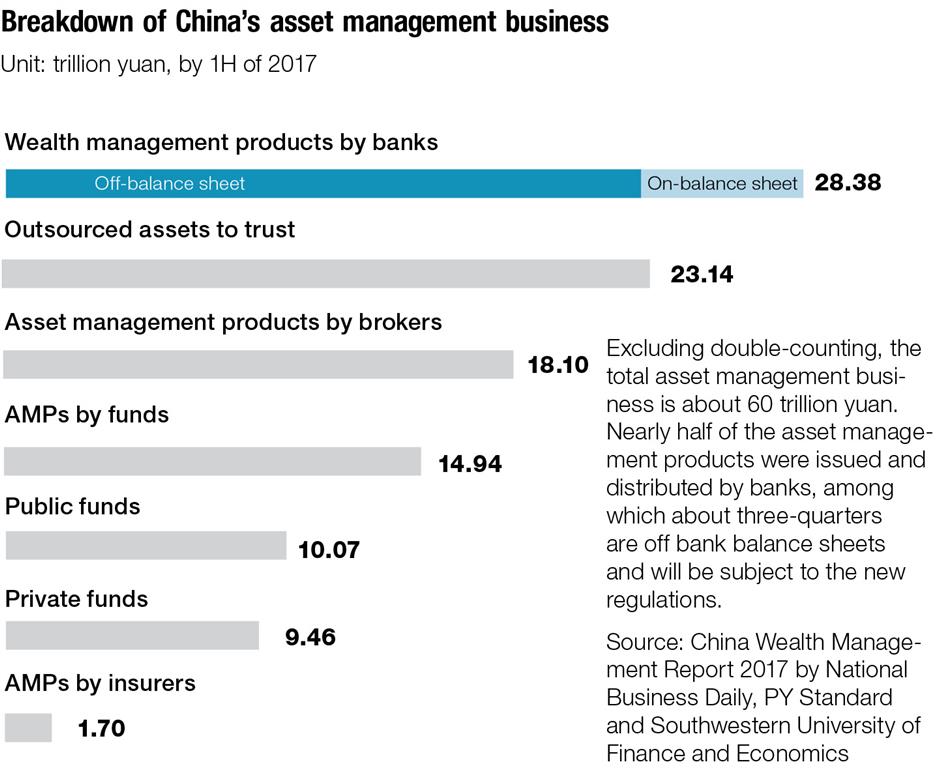

Parts of asset management fall into the “shadow banking” sector, which has been largely unregulated. At the end of the first half of 2017, nearly half of the 60 trillion yuan of asset management products were issued and distributed by banks, among which about three-quarters are off bank balance sheets and will be subject to the new regulations, according to a Nomura note.

Previously, banks attracted customers, especially retail individual clients, with verbal assurances that both principal and interest would be guaranteed, even though that pledge never appeared in writing.

“To put it simply, commercial lenders depended on the government’s credit to make money,” Li Jinjin, a senior researcher at Bank of Communications, told Shanghai Daily.

The strategy worked because customers basically trusted banks. Among those retail clients was a large group of older, wealthy women known as da ma, who blindly followed bankers’ advice.

“When buying wealth products, they do not bother looking at the fine print,” said investment professional Lin.

The new rules has set a grace period until the first half of next year and will require investment contracts based on net asset value once they are implemented.

Li said a study he conducted found that of 17 listed commercial lenders, fewer than 10 percent of their wealth management products were based on the net asset value.

When the new rules come into effect, investors rather than banks will be responsible for any losses of wealth management products they buy.

“Investors will have to become more risk conscious,” said professional investor Lin. “Money doesn't grow on trees.”

Suning’s Zhao said the new rules will have a big influence on how people invest. Some investors may return to lower-risk products like bank deposits or money market funds.

“My first response will be running away from banks and looking for alternative ways for investing,” said individual investor Liu, who disdains the idea of assuming personal responsibility for his investments. “Institutional integrity needs to be improved in China because there have been too many instances of malpractice.”

The most recent example occurred in mid-December, when Shandong Longlive Biotechnology Co defaulted on 140 million yuan in loans tied to an asset management product sold by Datong Securities Co.

The new rules also require banks to set up asset management subsidiaries to manage their products in the future. That may help ease the end of implicit guarantees, according to Sophie Jiang, a banking analyst at Nomura.

However, banks ultimately will figure out new ways to keep investors buying asset management products, Bank of Communications’ Li predicted.

“After all, we need clients to survive,” he said. “We have cried wolf for a long while, but now it seems that banks will have to make adjustments.”