One man's meat: rechanneling motorbikes we no longer ride

Some people use motorbikes to ride to work. Some use them to deliver meals. Some use them to take long-distance road trips. And then there’s Wu Yangde, who uses motorbikes to create unusual works.

In his studio sits what looks like a carburetor. But insert a small key into a hole in the back, turn it several times and out comes a stream of music.

With the addition of a small, round piece of sheet metal and a long metal stick — all old motorbike parts — to sides of the carburetor, the creation resembles a knight with sword and shield. Wu made what he calls the “Music Box of Knight” as a wedding present for a long-time buddy.

His 10-square-meter studio is located behind a moped garage in suburban Fengxian District, along with other works he has made from cannibalized motorbike parts.

Wu Yangde works in his studio, turning waste into creative works.

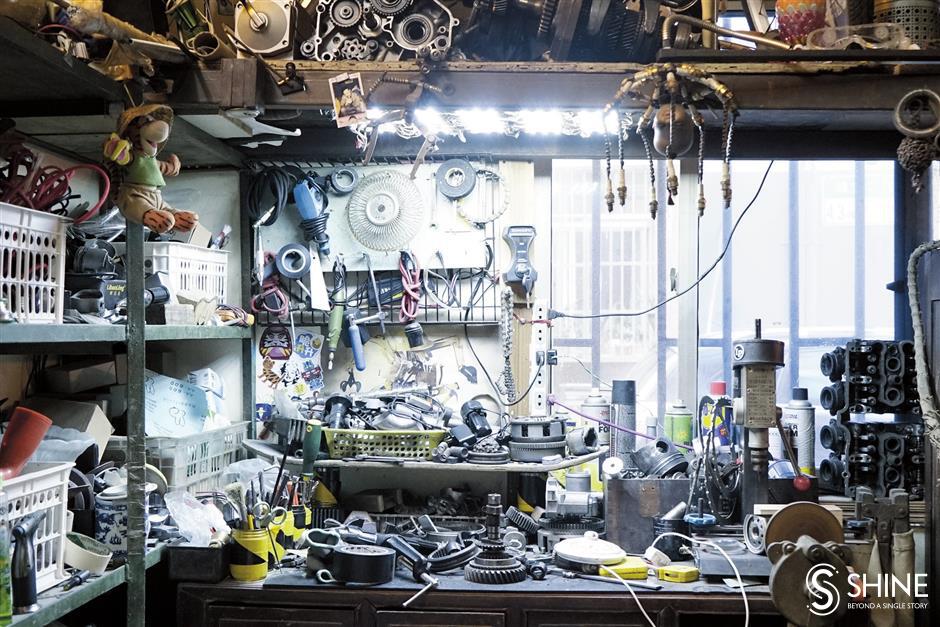

Wu, born in Yingshang, a county in Fuyang City in Anhui Province, is the owner and chief mechanic of the garage. He spends a lot of time in his small studio, which might look like a junkyard to most people. Two worktables, one in the middle and the other in a corner, are piled with all manner of tools and materials Wu has collected from motorbikes, mopeds and old furniture.

“One man’s meat is another man’s poison,” Wu says. “All the ‘junk’ are treasures that could be used in my future works.”

He came to Shanghai in 2000, where he earned a living by scavenging for about three years before going to work repairing motorbikes and mopeds. He eventually was able to own his own garage.

“One day a friend of mine showed me a short video of how a foreign artist used waste materials, and I thought maybe I could do that,” Wu says. “At school, handicrafts were my favorite class.”

His first piece was a lamp made of motorbike parts. No part, including the light bulb, was bought in a store.

“I actually once had a moped dealership, apart from the garage, but it closed eventually,” he says. “And I was not willing to throw away the LED-light signboard because it cost me quite a lot of money. My lamp was a better use of the bulbs than throwing them in a trash can.”

Wu took the lamp to the annual party of a motorbike club he attends as a prize for a lucky draw.

“I didn’t expect people to be so interested in the lamp,” he says. “They gathered around to take pictures of it with their phones. That gave me a lot of encouragement.”

Wu began to put more thought into his creations, often drawing inspiration from hotly debated issues.

Like the news last year that the last known female Yangtze River giant softshell turtle in China had died. Before her death, there were only four of the turtles left in the world. The other two, gender unknown, are in Vietnam. The species will probably become extinct soon.

The news saddened Wu and he decided to make a tribute to the species. His research found that Bixi, a legendary creature in Chinese myth, was actually based on softshell turtles. The myth goes that a Chinese dragon had nine sons, and Bixi was the sixth. Sculptures of the creature were typical décor under stone steles in ancient China.

“Bixi was very much worshipped as an auspicious animal, but its real-life descendants might become extinct because of human activity,” he says. “So I decided to make a statue of Bixi to heighten public awareness of environmental protection.”

The Bixi Wu made of bearings and gears

Made of bearings and gears in the steampunk style, Bixi is about the size of a grown softshell turtle. It has a movable head — shaped like a dragon’s — and four sharp paws. Its dark color exudes a sense of grief.

Wu says he likes to present contrast in his works.

“Take the carburetor music box for example,” he says. “Metals usually give the impression of cold and hardness, but the music itself is soft and tender.”

Another example of that is a bench in his studio, made from an old piece of furniture Wu found in a rural village with only its frame left. The seat board was gone, and the mortise-and-tenon joinery had rotted.

Wu repaired the frame and used gears and wrenches to make a new, hollowed-out seat for it. At first glance, it looks very similar to a traditional Chinese bench with wooden carvings, except that the carvings are actually metal parts.

“The wood frame of the bench feels warm, but the metal feels cold,” he says. “But they complement each other very well.”

The increasing notoriety of his creations is bringing in orders and also raising Wu’s stress levels. His perfectionism often makes him discard ideas and rough drafts. He takes long walks along the nearby Huangpu River to clear his mind.

One time, a big hurdle was overcome in a dream.

“I received an order to design three trophies for a motorbike-rebuilding contest,” says Wu. “I reckoned the trophies needed to be worthy of the participants’ efforts. I smashed quite a few initial starts because none of them looked good enough. Then, one night, I dreamed of a design, and in the dream, I thought, ‘This is it!’”

Half-awake, he got out of bed and sketched the design on a piece of paper before falling back to sleep. In the morning, the dream had slipped his mind, until he saw the draft sketch on his bedside table.

“My brain must have been working even as I slept,” he says. “The design of the trophies had really entangled my mind for so long.”

Looking like the lab of “mad scientist,” Wu’s studio behind his garage is chock-a-block with tools and salvage materials.

Wu admits it is getting more difficult to balance his creative work with his garage business. Fortunately, he has apprentice mechanics who pick up the slack.

“One of them is actually mentally handicapped, but I favor him a lot,” Wu says, with obvious fondness.

The young apprentice, who is about 20, often roamed the neighborhood and came to the garage to watch the work. He was sometimes bullied by local punks, Wu says.

“The young man said he wanted to learn mechanics,” Wu says. “I refused in the beginning because I didn’t believe he could do the work. But he came every day, always asking to be taken on as an apprentice. So I finally said yes, though I didn’t expect it to work out.”

But the young man took it very seriously. Although he managed to learn only a small part of moped repair in two years, Wu says he sees potential in him.

“He can now do work such as tire mending all by himself, and I see his eyes shine when customers come by and say: ‘Hey, shifu (master), check this out for me,’” says Wu. “I think he’s found self-dignity in the job.”

Wu has a lot of dreams. He wants to expand his studio and maybe hold a personal exhibition. He has already collected old wooden boards for partitions at possible shows.

“There are always new ideas in my head, and now, with the help of my apprentices, I believe I’ll have the opportunity to make my dreams come true,” he says.