Two sticks and a cord to set world records

In a yoga gym in Songjiang District, a row of bottles is lined up on a table. Pairs of them are balanced on their lips, with a playing card in between.

Martial arts coach Xie Desheng is warming up at the table, with a nunchaku in his hands. He is about to challenge the Guinness World Record for removing the most cards with a nunchaku in one minute without toppling the bottles.

He set a record last August by removing 14 cards. In February, Pakistani Muhammad Rashid superseded that feat with 19 cards removed.

Nunchaku, which originated on the Japanese island of Okinawa, is a martial arts weapon that consists of two sticks linked together at one end by a short chain or cord. The weapon was popularized by Bruce Lee in kung fu movies.

“Lee is my hero,” Xie says. “In fact, he is my virtual nunchaku mentor.”

The timer starts. Xie holds a nunchaku in his right hand and waves it rapidly toward the cards. A counter calls out the number of cards removed without toppling the carefully balanced bottles. The scene is tense because the stick at any moment might hit a bottle. If that happens, Xie has to start all over again.

Eventually, he manages to hit 20 cards in a minute without breaking a bottle.

“New record!” Xie shouts out in excitement.

Xie hits playing cards clamped between bottles with a nunchaku to set a new world record.

He will send the video to Guinness and expects to get a certificate in months.

Nunchaku, sometimes called “chuka sticks” or “karate sticks,” was originally a weapon of self-defense. It has now evolved into a sport of stunts — using the device to hit ping pong balls volleyed by a robot, to remove bottle caps, to snuff out candles and to smash walnuts, always in a prescribed time, usually one minute.

The device has spawned nunchaku sports clubs across the world, though its use is restricted in Norway, Canada, Spain, Chile and several other countries.

Born in the city of Chaozhou of the southern province of Guangdong in 1992, Xie left his hometown at 15 after his father died and mother left home. He didn’t want to burden his uncle by staying with him, so he went to bigger cities in the province looking for work.

He took jobs in factories and restaurants, but his life trajectory changed when a roommate introduced him to nunchaku. Xie’s interest was aroused.

After work, he often went to Internet bars to watch Lee’s movies, especially excerpts with nunchaku maneuvers. Then he would practice the moves from a video at home. As there was no explanation of the moves, Xie could only watch closely and duplicate his idol’s movements — again and again.

“The beginning was really tough,” he says. “I don’t remember how many times I hurt my head with nunchaku while training, and there were bruises all over my body.”

He went to gyms to improve the strength and tried to use nunchaku to do other weapons’ stunts.

“I believe that different types of martial arts communicate with each other well,” he says. “For example, I could do the movements of a cudgel with a nunchaku and vice versa. Practicing on one improves the other.”

It was obvious that Xie had a gift for it. Before long, his friends recommended he take part in various martial arts competitions. He went to Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan and Malaysia, winning several trophies, mostly on nunchaku.

The victories brought about dramatic changes in his life. He became a minor Internet celebrity and a martial arts coach. He travels around China, teaching in various places, and does training sessions for the Shanghai armed police.

Invitations to variety shows came with the fame. He remembers the first show where he appeared, called “Let Dream Fly.” It aired on a channel in the eastern province of Shandong Province several years ago. He admits he was nervous.

“For one thing, my hometown could receive the channel, so all my acquaintances there could see me on TV,” he says. “And for another thing, what I was going to do was very challenging, even dangerous.”

It was a William Tell sort of challenge, using a nunchaku instead of a crossbow to remove an apple from the head of a volunteer. It was difficult to find any people who were willing to rehearse the stunt with him, for obvious reasons.

“I was also worried that someone might try to imitate what I did on the stage,” he admits, with a laugh.

More show invitations and competitions followed. Xie felt stuck. The trophies no longer brought gratification. He was puzzled about how he could further challenge himself.

The Guinness World Records provided that challenge.

“You know, nowadays most martial arts competitions are judged by your movements rather than how well you can fight,” he says. “Most of the time you don’t even know which move you made to win a trophy. But the Guinness records are different. You can track your improvement through very straightforward numbers. It gave me very clear goals that I could challenge.”

His first record was set in Shanghai when he managed to snuff out flames on 52 candles with nunchaku in a minute, without knocking down the candles.

Then he learned a table tennis stunt with nunchaku, just like his idol Bruce Lee once did. He set a record for the most balls hit, with 35 in one minute.

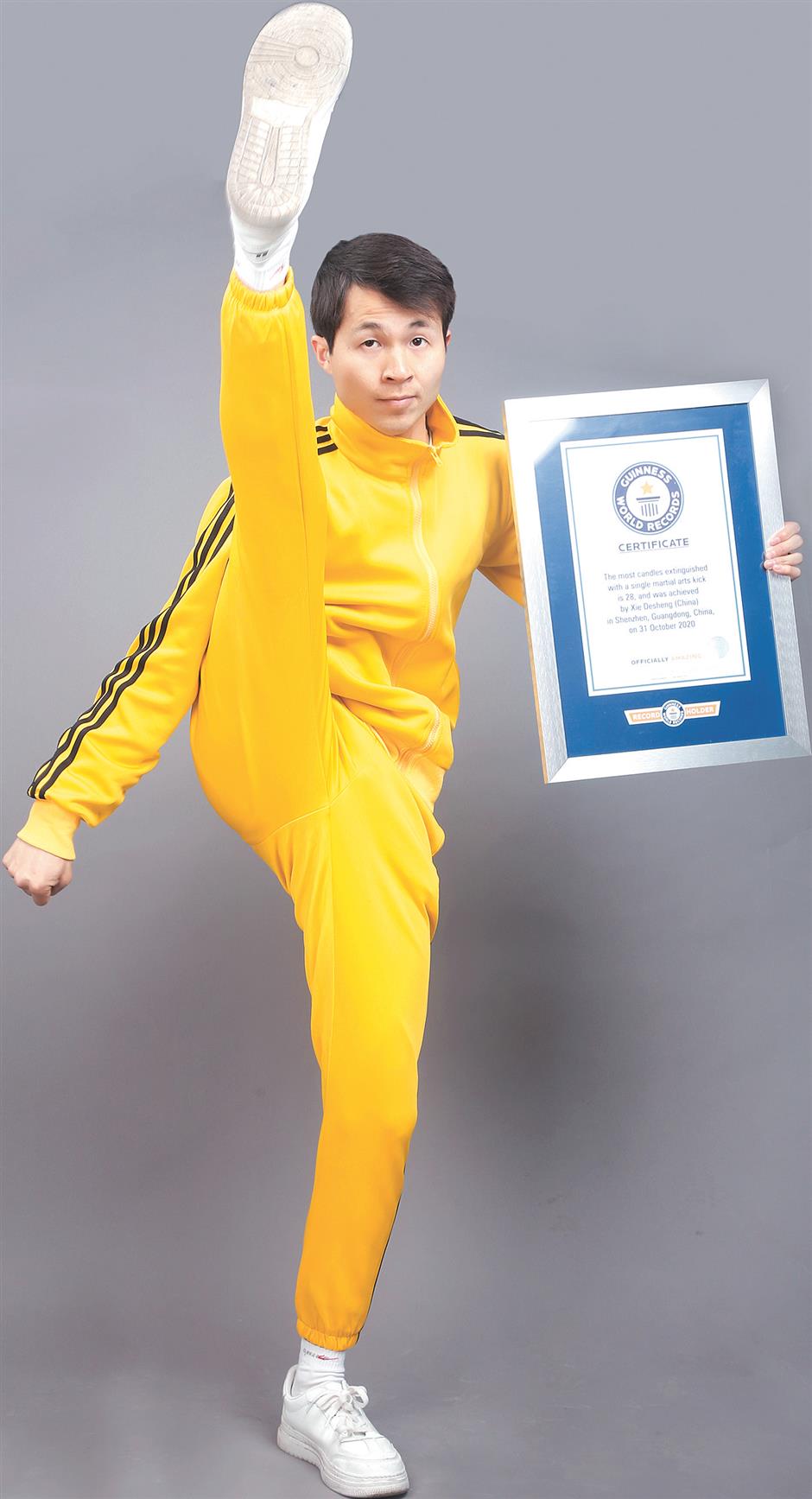

Xie poses with one of his Guinness World Record certificate.

“That was probably one of the most difficult challenges for me,” he says. “The sticks are thinner than a table tennis ball, and it feels much less solid waving a nunchaku than a ping pong paddle. After long practice, the motions became a kind of muscle memory.”

Not all challenges have ended in success. Last year in Beijing, Xie tried to open 10 beer bottles with nunchaku but failed.

The disappointing performance came in front of a large audience and local journalists.

“They asked me: ‘Will you be back again?’ And I said: ‘I’ll get up where I fell over,’” Xie says.

“A month later, I went back to Beijing and finished the challenge.”