Planning to study in the US? Decisions peppered with changing times

Karina Xing, 14, is facing a decision that could change her life. Should she include the UK and Singapore in her college plans?

The Shanghai middle school student is currently enrolled in a curriculum geared to applying to American universities and colleges. But if she can't get into a US school, she needs backup options and that takes time.

"It's not too early," she told Shanghai Daily. "Schoolmates and relatives even younger than me are weighing similar options. It's better to be prepared sooner rather than later because you never know what the situation will be four years from now."

Xing and her parents aren't the only ones in China grappling with uncertainty about plans for overseas study. Statistics on international students in the US and insights from industry experts show the trend started before the outbreak of coronavirus and has increased since then.

An analysis of recent US visa data by The Wall Street Journal showed a 50 percent decrease in visas issued to new Chinese students in the first six months of 2022, compared with the same period in 2019.

"Looking at this data alone does cause anxiety for people worried that the success rate of getting a student visa for the US is diminishing," said Bai Liheng, founder of Inspire!Education, which specializes in counseling students applying to American colleges and universities.

"Some Chinese families choose to apply for and accept offers from other English-language countries," Bai said. "There are many reasons for that, including fiercer competition and a decreasing acceptance rate. But we also see signs of Chinese families recovering their confidence amid concerns related to lingering pandemic issues or international tensions."

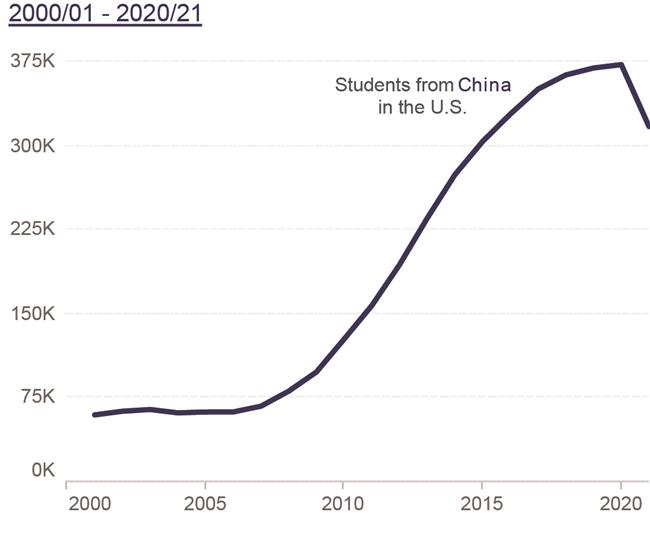

China remained the largest source of international students in the US during the 2020-21 academic year, accounting for around 30 percent. However, the number of students from China has fallen 15 percent, along with a similar decline in international students overall. And new enrollment in 2020-21 dropped 46 percent.

The figures were issued last November in the Open Doors Report on International Education Exchange. The same report in previous years showed a steady increase in numbers of international students – especially Chinese – studying in the US. The numbers increased over 20 percent each in 2011-12 and 2012-13, adding a third in four years to exceed 300,000 Chinese students in 2014-15. Then, it started to rise by single digit, going up by only 1.7 percent in 2018-19 and 0.8 percent in 2019-20.

"Some Chinese students who used to consider American schools their first choice are now applying for both US and UK institutions, some even choosing to accept British offers," Bai explained. "There are also international tensions and concerns over rumors that students applying for study in certain fields would have their visa applications rejected or not enrolled in schools."

She added, "This year, none of our students was rejected because of that. Recent policy changes and clarifications from US officials has shown positive signs for international students."

Back in September 2020, Chad Wolf, Homeland Security Secretary under then President Donald Trump, said his department was blocking visas for "certain Chinese graduate students and researchers with ties to Chinese military fusion strategy to prevent them from stealing and otherwise appropriating sensitive research."

At the time, China's Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian lambasted a move to revoke the visas of over 1,000 Chinese students as "outright political persecution and racial discrimination."

The sour official dialogue and spread of the coronavirus pandemic had a direct impact on students like Chloe Chen, who had just arrived at a university on the US West Coast.

"Classes were converted to online, and there were new COVID mandates every now and then," Chen said. "It wasn't the study experience I had anticipated for so long, and it stressed me out. Tensions were running high for a while, with everyone talking about tighter visa policies, especially for STEM students like me."

STEM refers to education in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. Chen, a freshman in 2020, was also worried about the prospects for future internships and jobs. She took a gap year after a semester of online classes and returned to China.

Earlier this year, under the administration of President Joe Biden, the US updated its policies to retain international STEM students. Changes include expanding the number of majors qualified to work in the US on student visas.

Early last month, Chen flew back to the US to continue her studies – hopeful that this time she will be able to enjoy real American campus life.

"I think it's all pretty much back to normal now," she said. "Friends and classmates are very upbeat now, unlike two years ago. My only concern now is the price and availability of a return ticket."

Felix Guan, a Shanghai-based counselor for students applying to study abroad, isn't quite so upbeat.

He has seen an increasing trend for students and parents to look at English-speaking destinations other than the US for four to five years.

"It's not just the travel restrictions and online courses that brought these concerns," he explained.

"COVID has changed the world and lives so dramatically, affecting how people look at studying abroad," he explained. "Three years on, students may not be worried about visa policy or travel restrictions as much, but many are concerned about COVID risks, the effects of recession and even reports of discrimination against Asians in the US."

Safety is one reason Xing's father cited when he asked her to consider study in other countries. He earned a master's degree in the US in the early 2000s and worked there for a few years before returning to Shanghai to start his own business.

Even before getting married, he envisioned his children following in his footsteps. No longer.

"Times change," he said simply. "I want my children to be prepared for whatever comes."