Directed by Andy Boreham. Shot by Andy Boreham and Zhou Shengjie. Edited by Andy Boreham. Subtitles by Wang Haoling, Hu Jun and Andy Boreham.

On April 21, 1927, a young New Zealander named Rewi Alley first stepped foot on China's mainland, right here in Shanghai at Dock 16. He didn't know it then, but he would go on to make a huge impact in China, and would remain here until his death 60 years later.

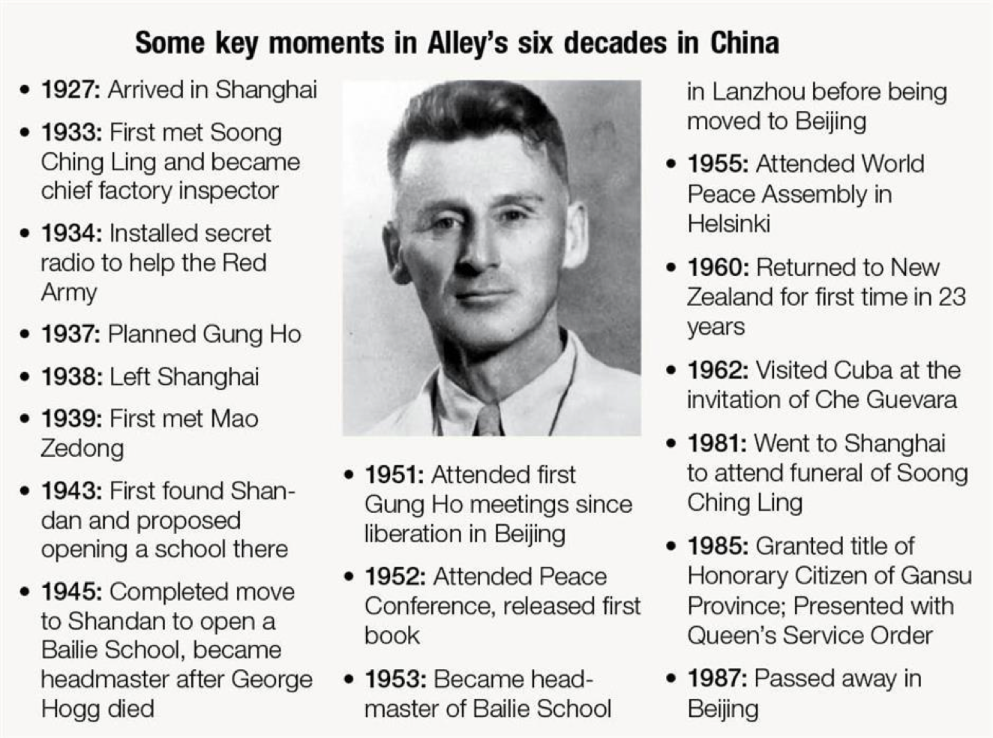

It's hard to sum up briefly what Alley did in China in those six decades, because he did so much.

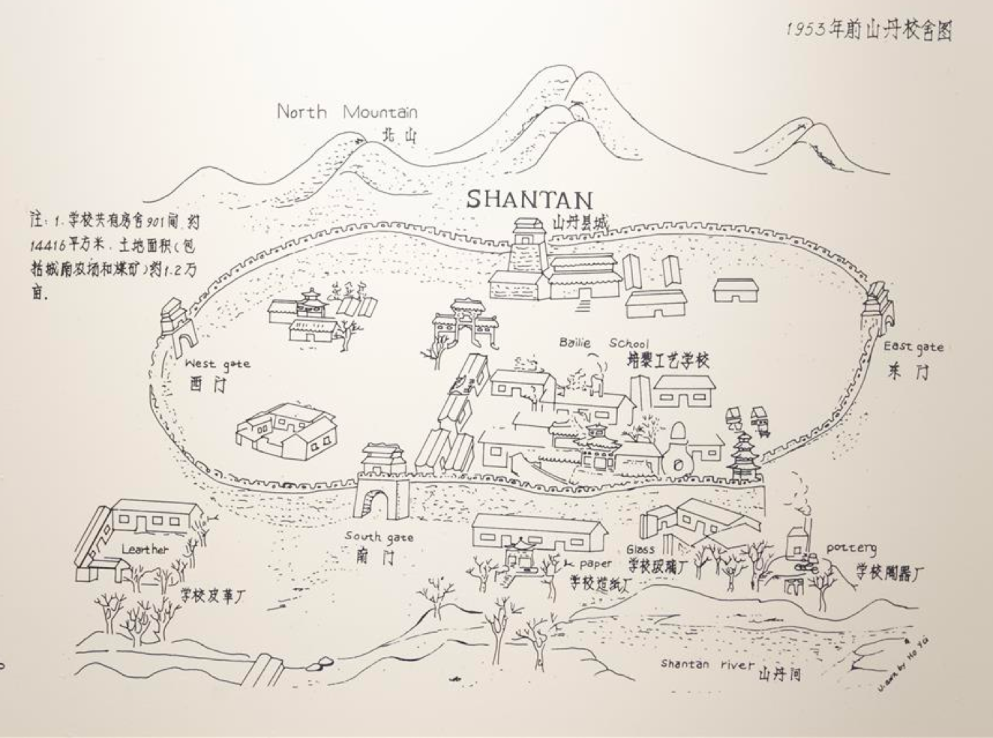

Some of his achievements include fighting to give child factory workers in Shanghai safer conditions and better treatment, helping set up the hugely influential Gung Ho cooperative movement to support Chinese industry under Japanese occupation, setting up and running schools for disadvantaged youth, fighting for world peace on behalf of China on the international stage, and fostering relationships and understanding between China and the rest of the world.

Alley's cousin, award-winning novelist Elspeth Sandys, explains who he was in simple terms. He was "a great humanitarian, I would say – a man with almost no personal needs or feelings that he was owed anything."