Aid work at high altitude

Huang Tao (center), deputy director of Sakya County's health bureau, attends a local celebration in Shigatse.

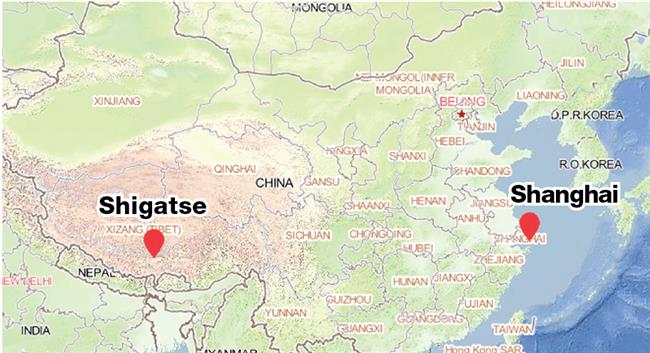

For more than two decades, Shigatse, the second-largest city in southwest China’s Tibet Autonomous Region, has been “paired” with Shanghai in a national program to share the expertise of its most modern cities with some of the country’s most backward regions.

The link is more than just lending assistance in economic, social, educational and medical realms. It has also created a loving bond between those who help and those who are helped.

Shigatse is a city-level prefecture located 280 kilometers southwest of the capital Lhasa on the border with Nepal. Its name translates as “fertile land.”

The city has one central administrative district and 17 rural counties. Its land area is 29 times bigger than that of Shanghai, yet its population is 29 times smaller. While Shanghai lies in an alluvial plain, Shigatse’s average elevation is 3,800 meters. The Mount Everest North Base Camp is located in the prefecture.

It’s a pretty daunting assignment to give up the modern amenities of life in Shanghai to spend a year or more so far from home, in such a different culture. But that hasn’t hindered the aid program, which worked on a rotation of teams, mostly educational and medical.

This summer, 55 of the 109 Shanghai participants dispatched to Shigatse last year, including teachers and doctors, are returning to Shanghai. A new team with one-year postings will replace them. Some 54 staff, mostly administrative, will stay on for two more years.

Tibet has long been a place of mystery to most foreigners, abetted by its elevation, by its remoteness, by its long history and by the written accounts of 19th- and 20th-century adventurers who visited the “roof of the world.”

For many Chinese, too, it remains an exotic realm. But for Shanghai aid workers who have lived and worked among the local population, Tibet is not so much mysterious as it is heart-warming. They have developed bonds of deep affection for a hospitable people who, despite poverty, extend a heartfelt welcome.

Ni Junnan, leader of the most recent team and vice mayor of Shigatse, describes it as “fusing blood.”

An ancient Chinese saying about teachers goes: “Peach and plum trees speak no words, but there are always paths leading to their fragrant flowers and tasty fruits.”

Shanghai volunteer teacher Zhang Qingqun discusses classwork with his Tibetan students at the Shanghai Experimental School in Shigatse.

Forty Shanghai teachers were sent on the path to Shigatse last year. None of them came home boasting of their accomplishments, but people in their home communities are well aware of the differences they are making.

Fu Xin, vice principal of the High School attached to Shanghai Normal University, headed up the Shanghai Experimental School in Shigatse, turning it into one of the best educational facilities in Tibet. It is the only school in the autonomous region that offers elementary-to-high school education under one roof.

“Our middle school students come out first in senior high school entrance examinations every year,” Fu tells Shanghai Daily.

His team introduced innovations like online classes, academic evaluations and a comprehensive database. To fill in some of the blanks of local education, the team wrote 27 books to serve as tutorial aides to standard textbooks, with the help of local teachers.

Lu Lu, an English teacher and researcher in Shanghai, wrote a vocabulary book for middle school students, while Pan Cheng, a high school geography teacher, compiled a book of “mind maps.”

The Shanghai teachers held training sessions with their Shigatse counterparts to help them learn the most modern educational methods.

According to a Tibetan-Chinese teacher at the school, the Shanghai contingent also elevated student interest in learning.

“To assist that, Shigatse students were paired with pen pals in Shanghai,” Fu says. “And Shanghai students donated books to the Shigatse school.”

Beyond education, Fu’s team has made humanitarian contributions to the local community.

The school has more than 100 orphans among its students, many of them survivors from the 2015 earthquake.

“Many of these children come to us unable to even write their names,” Fu says. “We treat them with respect and never give up on any of them.”

Team members also visit the orphanage for weekend activities and donate clothes and food to the children. What these children need, says one team member, is companionship and love.

“It’s sometimes hard to change their behavior because they haven’t been educated and don’t always know right from wrong,” Fu says, recalling one incident where an orphan nicked the clothes of another student to ward off the cold. “It’s hard to blame him for that. He just needs some guidance.”

Fu himself adopted a Tibetan orphan called Tenzin, who lost his parents when he was five months old.

“Every time I cuddle him in my arms, he smiles at me,” Fu says.

Liang Changming, from the Shanghai Xinyang Middle School in Putuo District, says he noticed that many of the local children were intrigued by science and technology. So he started a class on robotics. The children responded by making their own robots, which Liang says could match any made by students in Shanghai.

Liang once took them to Shanghai for a robot-making contest. His innovative thinking doesn’t end there.

“Taking advantage of Tibet’s special climate, I also plan to set a meteorological observatory for the students, with the help of the experts from Shanghai and Tibet,” Liang says.

Qian Songjie (left), director of Dingri People's Hospital, visits staff at a tent ward set up to serve patients at a village health center.

Another arm of the Shigatse project is medicine. In the Tibetan language, doctors are called aemje laa which sounds like the name Angela in English.

A group of six Shanghai doctors, led by Hou Kun, chief of infection management at Shanghai Pudong New Area People’s Hospital, is working in the Gyantse County People’s Hospital.

As current president of the hospital, Hou says outpatient and emergency cases at the facility last year rose 18 percent to 77,700. Surgeries were up 14 percent.

A recent case involved a man whose tractor collided with another vehicle.

“He was seriously injured, with a stroke, liver rupture and at least 10 rib fractures,” Hou says. “The difficulty we had was getting enough blood to give him transfusions.”

Tibetans believe it’s not proper to take the blood of another. There is no blood bank in Gyantse.

“Generally, under such a situation, the patient would be transferred to a higher-level hospital,” a surgeon on Hou’s team says. “But this man was in a very critical condition so we couldn’t do that. I used a conservative anti-shock therapy on him and put a tube into his chest four times to relieve the pressure the rib fractures were placing on his lung.”

The treatment worked and the man survived.

Shanghai doctors have also introduced modern medical procedures, like brain surgery, to Shigatse, and they are continuing their efforts to convince local pregnant women that prenatal checks are important before giving birth.

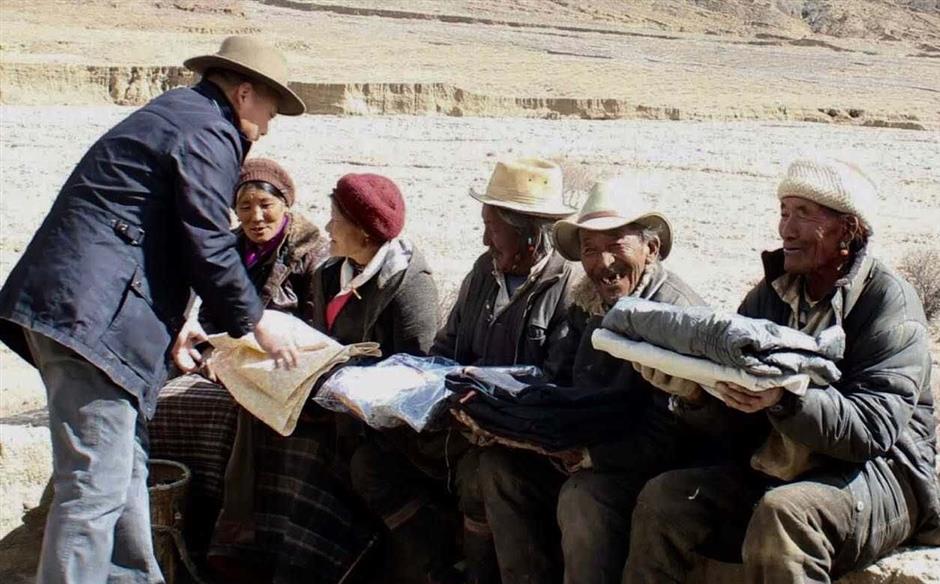

Tao Wenquan (left), deputy chief of Lhatse County in Shigatse, distributes warm clothing to villagers.

The local reception

Shanghai doctors and teachers are one side of the equation in giving aid to impoverished areas. The other side is the willingness of local people to accept the help. In the case of Shigatse, the welcome has been sincere and warm.

Tao Wenquan, a Shanghai aid worker, says it was sad to see the harsh living conditions of many people in the village where he was working.

During wintertime, when the temperature can plummet to minus 20 degrees Celsius, many people didn’t have warm enough clothing to protect themselves, Tao says. Some of them had to share one cotton-padded jacket in turns.

Tao organized a donation campaign and solicited hundreds of pieces of thick clothing, quilts, woolen blankets and books for the villagers.

“When I was about to leave, they didn’t want to let me go,” Tao says. “The whole village turned out to give me a salute.”

Tao says the aid workers were sometimes invited to participate in traditional local events like horse-racing and the celebration of Serfs Liberation Day. “They invited us to watch their dancing performances and asked us to join them,” Tao says.