Face to face with visions of ancients

Near sunset more than 1,600 years ago, a monk named Le Zun was traveling to Sanwei Mountain near Dunhuang, in today's Gansu Province. Exhausted, he decided to take a short break. As Le Zun rested, a miracle appeared in the setting sun before him: Buddha's halo.

The color-filled phenomenon on the horizon over the Gobi Desert cast its light onto Sanwei Mountain, revealing a thousand Buddhas bathed in a golden glow. Awestruck, Le Zun fell to his knees and began to pray.

Convinced that the area was a holy place, the monk raised money and built the first grotto in the cliff face opposite the mountain, dedicating it to the Buddha.

From this starting point in AD 366, hundreds of grottoes were built on the site over more than 1,000 years; from the Northern Wei Dynasty (AD 386-557) to the Qing Dynasty (AD 1636-1911), when minor repairs took place.

The vision seen by a weary traveler led to the creation of one of the largest and greatest cultural and historical sites in the world: the Mogao Grottoes.

The prosperity of the Mogao Grottoes was linked to the importance of Dunhuang City. The oasis city became a metropolis on the ancient Silk Road, commanding a strategic position between central China and the route to the west.

Merchants, monks and military forces from different nations made their homes there, creating a melting pot of cultures.

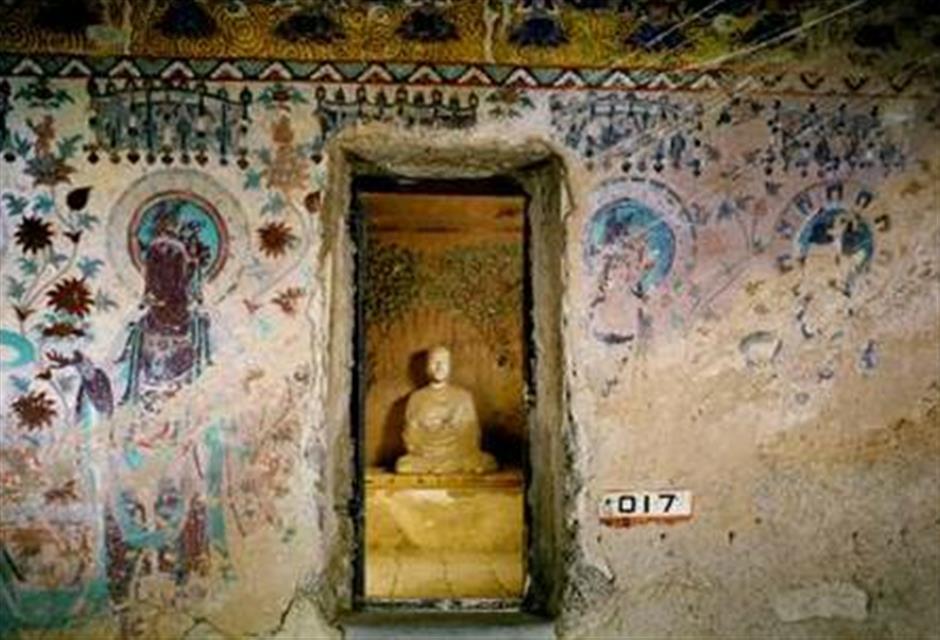

Initially, the caves dug into the cliff faces were created by monks to serve as places for meditation. Sculptures and murals were visual representations illuminating Buddhist beliefs and parables, as the monks were dedicated to promoting Buddhism in China.

As Dunhuang's prosperity grew and Buddhism became established, increasingly caves were sponsored by local people, ruling elites, temples and even Chinese emperors. These were intended as places of worship and pilgrimage for the public.

The Mogao Grottoes reached their zenith during the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907), when Dunhuang became the main hub of commerce along the Silk Road and a major center for Buddhism, by now it became the dominant religion in China. A large number of caves were created during this time.

Later on, during the Ming Dynasty (AD 1368-1644), the development of sea transport saw the old Silk Road linking Asia and Europe gradually abandoned, traces of its civilizations succumbing to the desert sands.

The millennia-long construction of the Mogao Grottoes was almost forgotten by the outside world, the site only used by local people for worship.

That was until the beginning of the 20th century saw a revival of interest in the ancient Silk Road.

It is now difficult to imagine Dunhuang's ancient glory days, but the Mogao Grottoes bear silent witness to the flourishing cultural exchanges of a long-gone past, embodying some of the highest artistic accomplishments in sculpture and mural painting the world has ever seen.

The 735 caves contain 45,000 square meters of murals and more than 2,400 sculptures. The complex forms the biggest ancient art gallery in China and one of the largest, best-preserved and most significant Buddhist art sites in the world.

World Heritage Site

The Mogao Grottoes are about 25 kilometers from downtown Dunhuang. There are no great views during the 30-minute drive; nothing but the wild expanse of the Gobi Desert. The cliffs, honeycombed with their famous grottoes, are the most prominent feature on the horizon.

Entering the UNESCO World Heritage Site, the first sight to catch a visitor's eye is the Nine-story Building, situated by the entrance.

This landmark was built during the late Tang Dynasty as a five-story pagoda and renovated in AD 966, during the early Song Dynasty (AD 960-1279). The present building was reconstructed in 1935.

This magnificent structure built on the cliff face seems like a guardian protecting the 2 kilometers of caves.

Inside the Nine-storey Building is the largest sculpture in the Mogao complex: the 35.5-meter-tall stone Northern Giant Buddha - the Future Buddha Maitreya.

The Buddha's features are typical of early Tang sculptures, with free-flowing lines depicting a round face, wavy hair and capturing the folds of the Buddha's robe.

The statue has been restored numerous times over the years to address the effects of weathering and other natural phenomena, such as earthquake damage.

The 26-meter-tall Southern Giant Buddha in Cave 130, also dating from the Tang Dynasty, is another exquisite Dunhuang sculpture. The Buddha's left hand, resting naturally and elegantly on his knee, has been described as "the most beautiful hand in the world."

An interesting note by the guide is that original statue parts dating back to the Tang Dynasty are in a more naturalistic and serene style than later additions. Reconstructed parts, even in the Song Dynasty which followed the Tang era, follow a much more stiff and rigid style.

Thus through the treasures of the Mogao Grottoes visitors can trace changes in religious and art styles through the flow of time.

Early works dating from the Northern Wei Dynasty feature more influences of the original Buddhism from the west, with simple figures and bold use of color.

Statues of Buddha from the Sui (AD 581–618) and Tang dynasties are more characteristic of central China's art: their figures full and round; the human form depicted in a more realistic manner; their colors more diverse.

A message from Fan Jinshi, director of Dunhuang Academy, the official institution protecting the grottoes and their art, encapsulates the importance of the site.

"These art treasures were created as a result of the transmission of Buddhism to China via the Silk Road. It was then spread throughout the Far East, gradually absorbing other influences on its way.

"Not only had the Chinese acquired a new religion, but more importantly, an entirely new style of art with characteristics integrated from different cultures was created.

"These achievements, the breadth of mind to embrace multiple doctrines and cultures, and the self-confidence to promote cultural development are characteristically strongly pursued by all receptive advanced societies."

The Mogao Grottoes are also known as the "Thousand Buddha Cave" due to the appearance of the Thousand Buddha motif on many murals. These follow the same style as the earlier caves to the west in Xinjiang, such as the Kizil Thousand Buddha Caves.

These recurring motifs were the result of many years of painstaking work from devoted artists. Today, some of the colors have faded or blackened due to the paint reacting with the air. But look close enough and you will see that each face of the Buddha, set in identical-sized squares, is unique.

Exquisite murals cover almost every corner of every cave; the Buddha in many forms, flying apsaras - spirits of the clouds - emperors, donors, ordinary people and animals, all in a fantastic procession of form and color.

Delicate colors and linework

The scale of the work is also impressive. It's said that if all the murals in the Mogao Grottoes were arranged in a line, they would cover 30 kilometers.

A major subject of the murals is "jingbian" paintings, which illustrate the Buddha's story to explain Buddhism to illiterate people.

Cave 61, one of the largest caves in Dunhuang, depicts Buddha Sakyamuni's life story in 15 scenes, from birth to departure after achieving nirvana. All the murals are very detailed, characterized by delicate colors and linework.

But what makes Cave 61 extra special are its other murals. As the cave was dedicated to famous Buddha Manjusri, an immense panorama of Wutai Mountain - which is associated with Manjusri - occupies the upper part of the west wall, behind the main alter.

The 13.8 meters by 3.8 meters mural corresponds closely with the actual site. It depicts the landscape of the mountain, various activities of people and more than 170 buildings bridges with legible inscriptions, making it an ancient map as well as an artwork.

Another important feature of the Dunhuang murals is also seen in this cave: donors' portraits. During the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (AD 907-979) and Song Dynasty, portraits of donors increased in number and size.

Cave 61 was supported by local magnate Cao Yuanzhong, whose family controlled the Hexi Corridor area for 122 years around a millennia ago. They sponsored the renovation of existing caves and the construction of new ones, including Caves 61, 98, 100 and 108.

Today, the life-size or even larger portraits of Cao and his wives and relatives are still stand guard over these caves. The make-up on the faces of female figures is still quite clear after more than 1,000 years.

Stepping into the caves here is like embarking on a magical journey: you don't know what is waiting for you in the dark.

Beautifully colored murals; a majestic sculpture of Buddha; a large group of statues, each with vivid and different expressions; a great central pillar alter; casual doodles dating back 300 years; or just a small meditation cave - everything seems possible.

What is guaranteed, however, on a visit to the Mogao Grottoes provides a connection with history.

Gazing at this treasure trove of murals and statues, it's hard to imagine how our ancestors created all this in often pitch darkness, illuminated only by oil lamps; to comprehend how many years artists spent working on the thousand Buddha motif; and how the ancient people overcame the cold and dry conditions to dedicate their lives to prayer and meditation here.

Nowadays, the Mogao Grottoes attract archaeologists, artists and tourists from all over the world; fitting for a place that attracted merchants and artists from East and West for more than 1,000 years in the past.

Priceless manuscripts rediscovered ... then lost

Cave 17 of the Mogao Grottoes - also known as the Library Cave - is a relatively small cave among the more than 700 at Dunhuang.

Originally a memorial cave for a local monk named Hongbian on his death in AD 862 and featuring magnificent murals, Cave 17 was sealed off sometime in the 11th century.

When the small cave was rediscovered in 1900, it was found to contain a treasure trove of 50,000 ancient documents from between the fifth and 11th century.

These were "heaped up in layers but without any order," according to British-Hungarian explorer Aurel Stein, who was among the first people to see the unsealed cave.

The documents covered everything from Buddhist canonical works and Confucian and Taoist works to administrative documents, anthologies, glossaries, dictionaries and calligraphy exercises.

While most are in Chinese, a large number are in other languages such as Tibetan, Uigur, Sanskrit, Sogdian, and the then little-known Khotanese. The find included copies of original manuscripts long-lost or previously unknown.

The discovery of the Library Cave opened a portal to ancient China and other central Asian countries, bringing Western explorers to the backwater on the ancient Silk Road.

Wang Yuanlu, the Taoist monk who discovered the cave by accident, was visited by foreign explorers, such as Stein and French sinologist Paul Pelliot.

Offering extremely low prices, they persuaded Wang to let them "buy" these priceless national treasures of China and took them to the West, together with sculptures and murals cut from the grottoes.

The manuscripts from the Library Cave spurred global interest in the Mogao Grottoes - leading to a branch of study called "Tunhuangology" - and archaeologists and artists swarmed to the site.

Today, almost 80 percent of the Dunhuang manuscripts are scattered overseas in Britain, France, the United States, Germany, Russia, Japan and other countries.

Some are in the collections of museums and other institutions; others are in the hands of private collectors.

A small museum is attached to the Mogao Grottoes, located in front of the Cave 16. The museum features many photographs of the manuscripts, providing a glimpse of the magnificent art works and valuable historic documents that were taken from China.

If you go

Other places worth seeing:

Yulin Grottoes: These feature sculptures and murals similar to those found in Mogao. Although smaller than the Mogao Grottoes, this is still a magnificent site. The Yulin Grottoes are about 170 kilometers from Dunhuang.

West Thousand Buddha Caves: The creation of the West Thousand Buddha Caves started even before work on the Mogao Grottoes. They are located 35 kilometers from Dunhuang.

Mingsha Mountain and Crescent Lake: Mingsha Mountain - literally "Echoing Sand Mountain" - is one of the most famous sights in Dunhuang, with the Crescent Lake at its center. They offer a magical combination of desert and oasis.

Yangguan and Yumenguan: The two most important passes on the ancient Silk Road, these were frontier defense posts between ancient China and the west. Today, only parts remain in the desert. Yangguan is 70 kilometers from Dunhuang and Yumenguan 90 kilometers from the city. A one-day tour can cover both.

National Yardang Geology Park: The word "Yardang" refers to the unique rock formations created by wind erosion. In the national park, 150 kimometers from Dunhuang, are strange formations in shapes said to resemble creatures such as lions, dragons and elephants. Watching sunset here is a breath-taking experience.

How to get there:

You can fly to Dunhuang City directly from big cities such as Beijing and Shanghai. Or you can fly to Lanzhou, the capital city of Gansu Province first, then take an overnight train to Dunhuang. Buses leave from downtown Dunhuang, in front of Silk Road Hotel, to the Mogao Grottoes every 30 minutes.

Where to live:

The Silk Road Dunhuang Hotel: Located right beside Mingsha Mountain, the hotel is built in an ancient castle style and its decor creates a typical northwest China vibe.

Dunhuang Hotel: in downtown area.

Where to eat:

Shazhou Night Market: The famous night market covers everything you need to try in this northwest small city; from mutton stew and kebabs to local yogurt and fruit. The stalls in the open air market are linked up, so grab a seat wherever you want and order from different places nearby. The owner will bring the food to you.

Tips:

Photography and touching artworks in the caves are strictly prohibited.

Admission for the Mogao Grottoes: 180 yuan (US$28.96) with foreign language guide service during high season (April 1 to October 31) and 100 yuan during the low season (November 1 to March 31).

All visitors must be accompanied by a guide provided by the Dunhuang Academy.

In order to protect the caves, only some are open regularly and others on a rotation basis. The schedule changes each year. Check the Dunhuang Academy website at http://enweb.dha.ac.cn/index.htm.

The temperature can rise to above 30 degrees Celsius at noon and drop to freezing at night, so dress accordingly.

Bring sun cream. Although it is cool inside the caves, you may have to wait outside under the blazing sun.

Bring your own flashlight to get a clearer view inside the caves.