Japanese artist uses work to press green issues

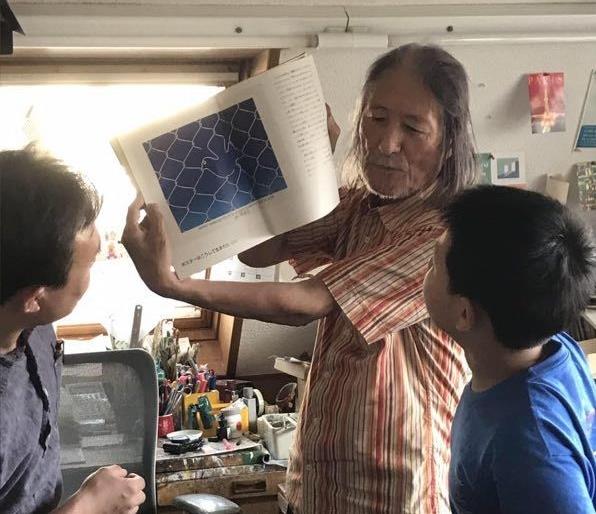

U.G. Sato shows his work to children at the Xiaoyan School of Art in Shanghai.

For famous Japanese poster designer U.G. Sato, the environment is inarguably the most pressing issue of our time, which is also the main subject of his work.

“I naturally pay attention to it. As a poster designer, I can use direct visual language to transcend barriers and pass the information to everyone in the world,” says Sato, who was in Shanghai last weekend. “So I don’t pursue complexity in my work. I want it to be as simple as it can be.”

A committed environmentalist and pacifist, Sato’s award-winning poster designs were displayed at the Shanghai Jing’an Children’s Library in an attempt to pass his ideas on to children.

The works included possibly his best-known poster, “Peace,” showing broken fences in the shape of a pigeon, and “U.G. Sato’s Style of Evolution” where a woman stands elegantly on a man-shaped high heel.

“Protest Nuclear Testing by France” is a work Sato created to protest widely condemned French nuclear tests near French Polynesia, a former colony in the South Pacific.

Combining humor with political theme, Sato’s work won a bronze prize at the International Poster Triennial in Toyama, Japan.

“Protest Nuclear Testing by France”

“Peace” created in 1978

Born in 1935, Sato graduated from Kuwasawa Design School in 1960 and established his personal workshop in 1975, called Design Farm. He specializes in poster design, picture books and monuments.

Known as a leader in using art to address serious issues, Sato tries to blend humor with simple visual language so that the audience can understand the deeper meaning behind without too much thinking.

Sato spent his childhood hiding in the countryside from US air attacks during World War II. This experience shaped his understanding of the world and might be the reason why he has put so much effort into addressing environmental problems.

“Forests, streams, birds and insects that I found in nature stuck in my mind. I learned to use natural elements to symbolize my imagination,” he says.

Even the self-designed logo for his studio is filled with natural elements, including ginko and persimmon trees and resting birds.

“Although I have lived an urban life for a long time, the countryside vibe has left its mark on me,” says Sato. “I don’t drive. I only walk or ride, which gives me a closer look at the beauties that life is offering.”

The inspiration for another famous work “Peace,” he says, came from broken iron railings which kids used to sneak into the playground.

Sato designed the logo for Shanghai’s Xiaoyan School of Art. He used three roaring pigeons to symbolize the imagination and dreams of children flying high in the art kingdom.

He was invited by the school to hold lectures for students and display his work. He also went through posters designed by the children.

“Their paintings varied from age, but it’s clear that they enjoyed the process and that’s all that matters,” he says.

“How much the children understand Sato’s works is not important,” says Hu Richa, headmaster of Xiaoyan art school. “The Musée du Louvre doesn’t shut doors to children. On the contrary, it’s important for kids to have access to masterpieces from an early age.

Song Yingchen, mother of a 10-year-old who was one of the students, agrees.

“Cultivation is important. It doesn’t work magic immediately but a person soaked in art while growing up surely thinks differently and is more observant.”