Giving worn art renewed vigor

Li Lingen, a master in restoring ancient paintings

Li Lingen, who was born in the rural Shanghai town famed as China’s “center of farmer art,” has become a master restorer of such distinction that ancient paintings he has rehabilitated are sought by collectors and museums far and wide.

For his workmanship and devotion to preserving valuable Chinese art legacies, Li was among the first workers in the city honored with the title of “Shanghai Standout.”

Li, 60, lives in Zhonghong Village in Jinshan District, which is home to the China Farmer Painting Village, where artists in the two-dimensional folk art genre work and sell their paintings to the public.

Li and his wife Li Jinhua, whose mother was a first-generation farmer painter, started their careers in art by framing paintings in a village workshop in the 1970s. Twenty years later, they began restoring ancient Chinese paintings and calligraphy for collectors, art houses and museums.

Chinese artworks, painted on paper or silk, can become brittle in time. Some paintings brought to Li Lingen are literally in tattered pieces.

“In the past, people used to burn straw and wood to keep a house warm, but that environment was damaging to paintings,” he says.

Li checks the damages (below) of a painting before repairing it.

All Chinese paintings are mounted, meaning that paper or silk is glued to the back of the painting to support it. Mounting is also the key to bringing out the beauty of a painting.

To restore a painting, back layers must be peeled off first. The whole painting is carefully soaked to soften the paper and glue, enabling layers to be removed more easily.

“Chinese painters use mineral paint, so the colors aren’t affected by soaking in water,” Li says.

It’s a time-consuming process. Li says he often has to get up in the middle of the night to make sure that the water hasn’t run dry and that no mildew starts to form.

Restoration can take 10 days or even as long as six months, depending on the nature of the painting and the degree of damage. This is a human skill that no machine can replicate.

In his work, Li uses an array of special tools, including a thin, long wooden ruler to part the layers of paper and a small iron stick to tame the irritated thin layer of painting during the process.

It’s like puzzle at times. Since the back layers have to be peeled off with the painting facing down on a table and all tattered pieces need to be in place, Li has to assemble the pieces solely based on their shapes, without seeing the surface of the painting. In some cases, that can take a whole day.

Li and his wife use a wood ruler to "demount" a painting.

Once the back layers are removed, a painting is backed with a piece of paper of roughly the same age as the painting, or with silk. Then Li and his wife paint any missing strokes.

“It’s a great responsibility to handle these art treasures,” Li says, noting that some paintings he has treated are worth millions of yuan. “It’s highly intense work. The moment of relaxation comes only when a client praises the final work.”

The couple are so renowned for their skills that they are overwhelmed by work. Li has to advise some potential clients that they should keep their painting because they might have to wait a long time to get them restored.

“Recently, one client persisted and said he can sleep well only if the painting remains with me,” Li says.

Back in the 1990s, Li used to drive into urban Shanghai to pick up paintings, Now, with better roads and more people owning cars, clients usually seek him out at home.

Li says he has no desire to move closer to downtown because high rents there would force him to put up prices — something he is reluctant to do. Currently, he charges for restoration based on the value of the artwork and the extent of damage to be repaired.

Oddly enough, though he lives in the farmer painting village, he doesn’t restore farmer art. It just isn’t expensive enough for people to want it restored, he explains.

Li adds strokes to a mounted painting.

In the past few years, a handful of young apprentices have come and gone. Li says some are already competent enough to mount paintings, but it takes at least 10 years of experience in mounting for one to rise to the challenge of restoring ancient paintings.

“In mounting, we deal with relatively new paper, but that’s not the case with restoration,” he says. “It’s only when you can mount new paintings 100 percent correctly that you can begin to understand older paper better.”

Li has some tips for art collectors, who often lack professional knowledge in how to preserve ancient Chinese paintings.

Instead of preserving a painting in a plastic bag, collectors are advised to use old newspapers to keep it dry. The printing ink on newsprint also helps protect against insects nibbling on the paper, he says.

Instead of keeping a painting in an iron box, storing it in a camphor box will keep an artwork fresh for a significantly longer period. Also, Li advises that ancient paintings shouldn’t be exposed to moist, rainy seasons.

Li's workshop is tucked away in the famous farmer painting village.

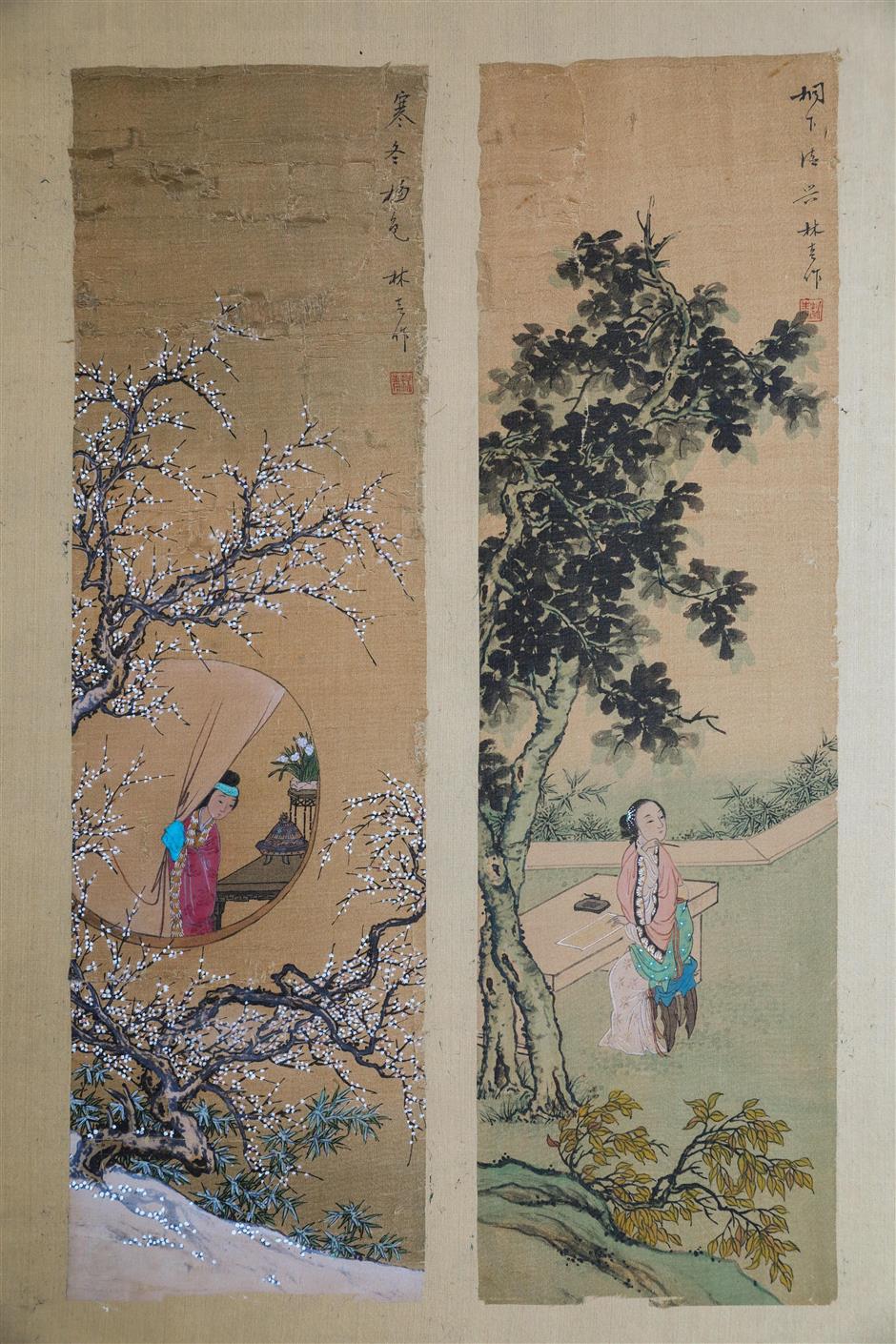

A painting from the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) is halfway through restoration process.