The art of keeping ancient paintings alive

When Liu Delong visited the Freer Gallery of Art in the US — one of the most important museums outside China noted for its fine Chinese art collections — in 2009, he found many of the paintings were detached from their original mountings and hung in glass frames.

“I can understand why they did so. They thought in this way they could avoid creases and tears on the already fragile paper,” said Liu. “What they did not know was that Chinese paintings cannot be called so without the mounting. It is like wearing clothes for it.”

The craft of mounting is a 2,000-year-old tradition in China, an essential part of the appreciation and collection of Chinese paintings and calligraphy, which are mostly done on xuan paper, silk or brocade.

The mountings protect the artwork embedded inside and enable easier transportation, storage and display. And they also have their own aesthetic functions.

Liu Delong fills up color, a critical skill in his mounting process.

Liu fell into the profession by an art conservator by accident.

He started as a security guard at the Zhejiang Provincial Museum but at the end of 1987, he was moved to the conservation department which was desperately short of hands.

“I started learning from my master, Zhao Xuemin, who studied mounting at the Shanghai Museum in the late 1970s,” explained Liu.

Like all ancient craftsmanship, the specialized techniques of mounting are imparted to the next generation through an apprenticeship. Places like Shanghai, Yangzhou and Suzhou used to be centers for top masters in mounting across the nation. And these people worked for private antique shops or mounting shops.

In the 1950s when national and local museums began to build up their own conservation teams, the masters were summoned to work and teach in the museums.

Liu had his own student four years ago. Yuan Kun, who is now in his late 20s, came to work at the museum in 2014. He has received his degree in antique book conservation at the Jinling Institute of Technology in Nanjing.

“I touched upon some basics about mounting during college, but still the actual work requires a lot more care and labor than I thought,” said Yuan.

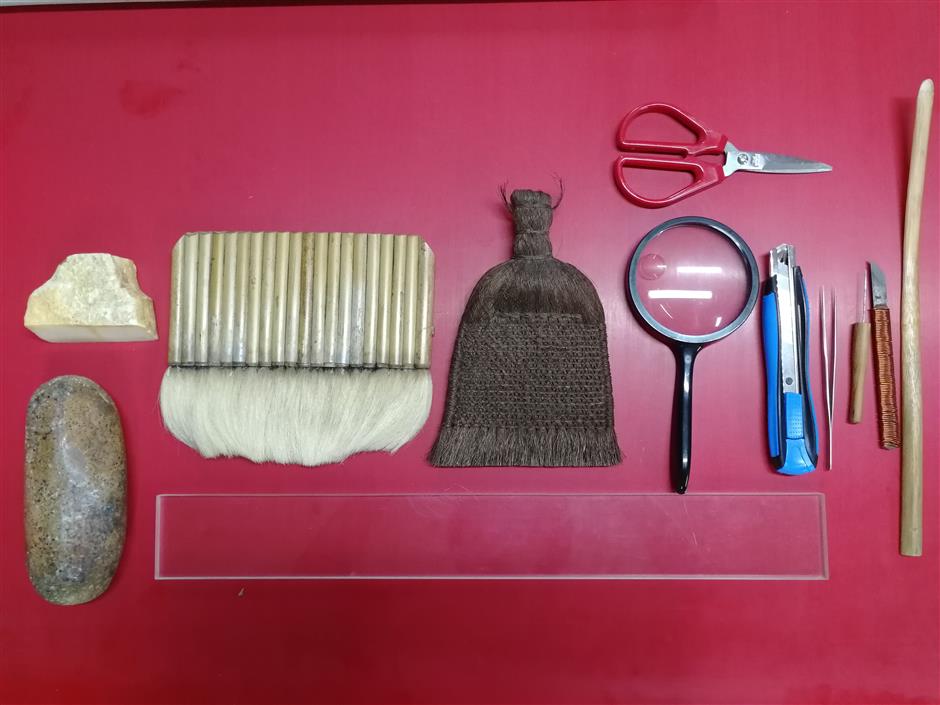

In a studio covering less than 30 square meters, Liu and Yuan showed to Shanghai Daily the tools they used daily during their work.

The paibi (排笔), which is made of several goat-hair ink brushes fixed on a row, is used to apply paste or water. The zongshua (棕刷) — palm-fiber broom in a version without the broomstick — is a handy tool for smoothing and cohesion.

There is also the bamboo strip, the pebble stone and the Chinese insect wax, tweezers and the awl, each corresponding to a necessary step in mounting and re-mounting.

“Every beginner has to learn the rudiments first, including how to use a palm-fiber broom or how to produce the starch paste with the right concentration,” said Liu. “And as a green hand, you are not allowed to work on antiquities, you start from one of those new paintings.”

Liu and Yuan are in charge of repairing all the ancient Chinese paintings and calligraphy in the museum and they also receive assignments from other city and county-level museums within Zhejiang Province.

It takes from one to several months to finish conservation work on a single piece. Depending on the condition of the piece, it may be a major overhaul or minor treatments here and there. The former usually requires re-mounting.

To understand how a mounting or re-mounting is carried out, it is necessary to know about the structure of a mounted Chinese painting and various formats and mounting styles.

Some of the tools used during painting conservation. From left: Chinese wax, a pebble stone for waxing, smoothing and softening, a brush, a palm-fiber broom, a magnifier, a knife, scissors, tweezers, an awl and a bamboo strip.

A piece can be mounted as a hanging scroll (立轴), which is hung vertically, as a hand scroll (手卷), which is displayed on a table, or as a folded album (册页), which is kept like a book, among other styles.

In a hanging scroll for example, the original painting, or huaxin (画心), is consolidated with up to four protective paper layers at its back and mounted with silk or paper borders. The rod attached to the upper edge of the scroll is for hanging purposes while the one at its lower end is a roller.

The mounting styles vary from one-color to two-color, three-color and Song Dynasty (960-1279), requiring different choices and combinations of borders and decorative strips at the front of the painting.

If a painting needs to be re-mounted, it usually means that all its backing paper has to be stripped off. The layer directly attached to the painting is called mingzhi (命纸) and is considered the most important part in any mount for extending the life of a painting.

Removing such a layer is thus a crucial step in re-mounting and requires a great deal of experience and focus.

It comes after the painting is cleaned and is usually done while it is still damp. Conservators focus for hours as they peel away the sheet slowly and gently with their fingers or with tweezers.

The wall inside Liu Delong’s studio where re-mounted paintings are dried for a couple of days before they are fixed with rods or other functional or decorative parts.

“But if the painting and its mingzhi are in relatively good condition, this step is unnecessary,” said Liu.

Most of the age-old paintings suffer from creases, rifts and worm holes. These places are to be reinforced at the back with stickers. The material and color of the stickers must be the same or as close as possible to the original texture of the painting itself.

The last step is to fill in the color in the reinforced area on the front side until these traces of repair are almost invisible.

After all protective measures are taken, the mount will be very similar to the original, unless previous work was not done properly.

“If everything goes right, a nicely re-mounted ancient painting can stay in good condition for a hundred years,” said Liu with a pride.