Gloss of an ancient art form never wanes

This lacquer artwork by Shi Jianping in the 1970s features the mural at the Fahai Temple.

Wang Shijun, a lacquerware collector and the founder of the Shanghai Art of Lacquerware Museum

Chinese lacquerware, dating back some 8,000 years, is durable, waterproof and artistic — the exquisite artwork of multilayered varnish that is often carved, inlaid and painted with flora, fauna, landscape, mythology and religious figures.

Wang Shijun is a collector of lacquerware and the founder of the Shanghai Art of Lacquerware Museum in Minhang District. He is passionate about the enduring culture of lacquerware, which has played such a prominent part in Chinese artistic tradition.

Lacquer is derived from the sap of the Chinese lacquer tree — scientifically called Toxicodendron vernicifluum — which is cultivated in most Chinese provinces.

Like the rubber tree, the tree exudes a milky, sticky white sap that serves as a protective agent against tree wounds. To collect the liquid, cultivators slash 10-centimeter lines on the trunk. On contact with air for some time, sap turns a chestnut color.

The liquid extracted from the tree sap contains urushiol, a caustic and toxic substance that causes allergic reactions in some people.

“I had edema and my body was extremely itchy,” said Wang after an experience he had last year.

“I once heard from some elderly cultivators that the juice of garlic chives and a broth of boiled camphorwood could relieve the symptoms,” Wang said. “With the broth of boiled camphorwood, I recovered 10 days later without any scars or after-effects.”

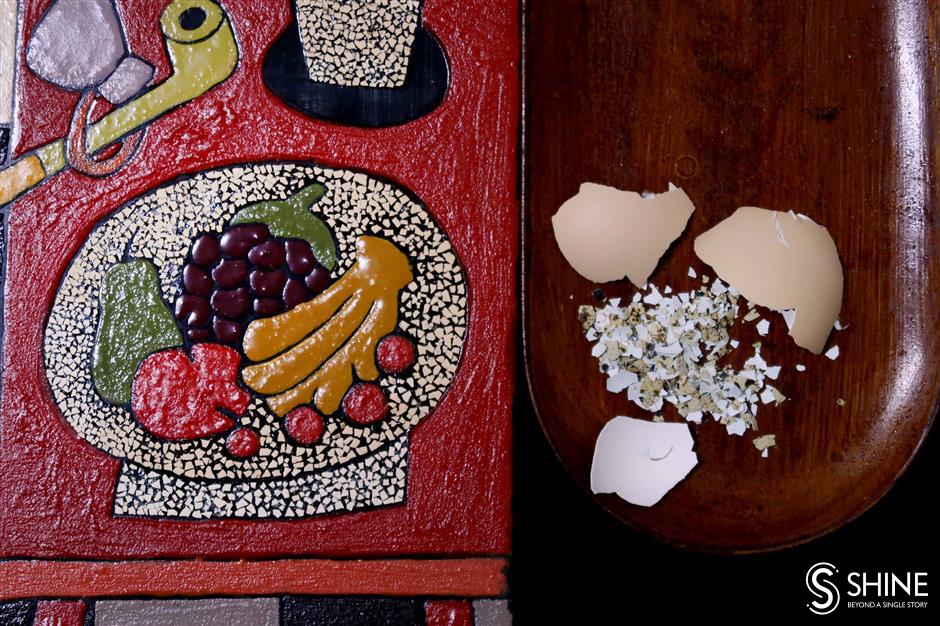

Eggshells, abalone shells, pearls, micas and gold leaf are among the materials used to decorate lacquerware.

Apart from its ornamental value, lacquerware is also practical. It is often used as containers, tableware and furniture. Thanks to the coatings of lacquer, the ware is resistant to heat, acid and damp.

Eggshells are used to decorate a lacquer artwork.

The lacquerware museum displays the whole process of making lacquerware, Wang even has the model of a Chinese lacquer tree in the museum, along with all the tools of the craft.

According to Wang, 1,000 cuts on a tree can produce only 500 grams of lacquer. There are merely 15 to 17 weeks of the year suitable for collecting lacquer, mainly in summer.

“The lacquer tree also features in traditional Chinese medicine, used as an anti-coagulant,” Wang said. “I once ate stir-fried lacquer tree leaves and eggs in Yunnan, which tasted quite good. People also can press oil from the seeds of the tree.”

As early as the Neolithic Age (which started about 10,000 years ago), ancient civilizations had discovered and were using the raw material. The earliest lacquerware found in China to date is a bow excavated from the Neolithic Kuahuqiao site in Hangzhou.

Because extracting lacquer from trees is so demanding, modern lacquerware makers often use chemical varnishes instead.

“The gloss of wares made of lacquer is gentle and warm, while the finish of chemical varnish tends to be more dazzling,” Wang said. “In addition, the color of the natural coating changes with time, which doesn’t happen with chemical varnishes. Lacquer is living and can breathe.”

With minerals added to the sap, lacquer takes on different colors. For the two most common colors of lacquerware, black is achieved by adding coal ash, and red by adding cinnabar.

A lacquer jar donated by the descendants of Xie Dazhong, who owned a lacquerware studio in the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911)

The lacquerware process is sophisticated. The first step is to make a base with pieces of aged, very dry wood. The wooden core is covered with ramie cloth and roughcast in order to create a flat surface, which is further coated with layers of lacquer.

“A 1-millimeter-thick lacquer requires 18 to 22 coatings,” said Wang.

However, only one or two layers of lacquer can be applied in one day because the lacquer dries slowly in humid conditions with a room temperature of around 20 degrees Celsius. The preceding coating must be dry before the next is applied.

Wandering through Wang’s museum, I pointed at a completely red lacquer artwork and asked Wang how long it took to make.

“At least two years,” he replied. “The artwork is in the technique of carving, which is a distinctive Chinese form of decorated lacquerware.”

According to Wang, craftsmen must apply numerous layers of lacquer first, and then carve into the very thick coatings. During the process, the surface must be just right, neither too dry nor too wet. That poses a challenge for craftsmen to work quickly.

“Once a mistake is made, all the work done previously is in vain,” Wang said. “Lacquerware needs a group of people working together.”

Woodworking, lacquering, carving, inlaying and painting. Each procedure is done by a separate craftsman. With the closing of the Shanghai Lacquerware Carving Co, production of lacquerware has decreased, and the skilled craftsmen of old hardly ever congregate.

Originating in Yangzhou, Shanghai-style lacquerware is mainly made into furniture inlaid with bone and stone. In the 1970s and 80s, lacquerware was a primary means of earning foreign exchange in Shanghai. To cater to foreign customers, the lacquer furniture was designed in Western styles and inlaid with colorful materials.

“Before 2010, I focused on the collection of lacquerware,” said Wang. “Having known several masters of the art and acknowledging that their works were superior, I commissioned them to make lacquerware in 2013.”

The museum houses the studios of the craftsmen. Wang aims to continue old traditions and provide a place where lacquerware can be preserved and enjoyed.

The museum is currently undergoing a renovation. Wang said it will exhibit more delicate works when it reopens to the public in the future.