Author's book illustrates a century of type

Graphic designer Jiang Qinggong

Graphic designer Jiang Qinggong has just published another in his much sought-after media artifacts books chronicling Shanghai.

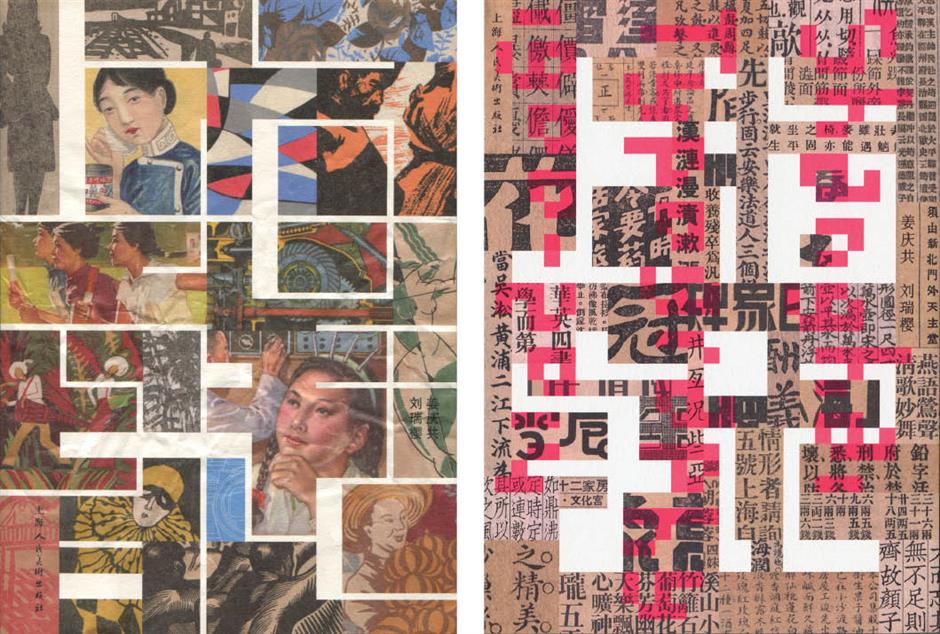

A sequel to “Shanghai Typography 1900-2014,” which was listed in the most beautiful books in 2015, “Shanghai Illustration 1900-1999” continues where he left off with old-book style designs, arty illustrations, prints and posters developed in Shanghai over the past 100 years.

“Dear readers, please don’t be surprised when you see a wrinkled cover. We just wanted to use it as a metaphor of how we felt during the process of wallowing in old books. And I look forward to sharing my feelings with you,” Jiang says on the left hand corner of the book.

From the portraits found in late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) novels, to lithographic prints introduced by Western missionaries in the early 20th century; from Duoyunxuan woodblock watermark prints, now listed as intangible cultural heritage, to commercial packaging in the 1930s in the wake of a widespread nationalist movement, and from political slogans to fashion covers and movie posters since China’s second stage of reform and opening-up in the late 1980s and 1990s.

Left: “Shanghai Illustration 1900-1999” has assembled more than 400 works from 249 Illustrators, artists and designers. Right: “Shanghai Typography 1900-2014” traces the development of the writing and designing of the Chinese characters of Shanghai in the modern era.

The book has assembled more than 400 works from 249 illustrators, artists and designers in chronological sequence to outline the centennial development of visual art by the local publishing houses and commercial ad agencies, featuring a strong human characteristics of life in Shanghai.

It has further extended the inquiry into the cultural ecology of Shanghai illustration art through nine interviews from persons who are related, directly or indirectly, to the development of Chinese media artifacts, such as professor John Crespi from the Colgate University, Ren Meijun, one of the female designers with the Shanghai Advertising Co Ltd, Cai Kangfei, who used to do scientific illustration with the Shanghai Science and Technology Press, and Li Shude, a movie-poster artist with the city’s Caoyang Cinema.

“For the first 3,000 copies, each cover was hand-crushed by workers in the printing house before it was plasticized and packaged,” said Jiang. “Imperfection is not only a special design technique that needs to be recorded, but also serves as a gentle reminder to readers of the value of handmade products.”

Left: “Shanghai Height,” by Jiang Qinggong, 2017; Right: Illustration from “China in Sign and Symbol” (1926), Kelly & Walsh Ltd

Starting in 2009, the 60-year-old has collected tens of thousands of printed materials, such as newspapers, periodicals, books, movie posters, advertisements, calendars, match boxes, theater tickets and program lists, from second-hand bookstores, markets and personal collectors.

The wide-ranging content of these popular illustrations, Jiang explained, is reflected in the eclectic topics he takes on in the book. Indeed, to read “Shanghai Illustration 1900-1999” from cover to cover is to be immersed in a formidable array of cultural minutiae, all researched with admirable diligence from the late 1880s up through the new era of the Internet.

“A graphic designer myself, the highlight of the book, I think, goes to pictorials created and produced between the late 1960s and early 1980s, when resources were scarce and printing techniques were primitive. Some of the illustrations are highly valued due to their expressiveness, unique style and technical complexities,” said Jiang.

It was the Western mission presses that shaped the Chinese printing industry in the late 19th and early 20th century by importing electrotypes and lithographic prints from the United States and Britain, and training Chinese workers in new engraving and printing techniques which allowed them to establish their own publishing houses.

Though mechanical woodblock printing on paper started in China during the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907), the Chinese used only clay and wood movable type. The use of metal movable type was introduced by William Gamble, who was appointed as a missionary to China in 1858 by the Presbyterian Church in the US.

From then on, with Gamble’s printing operation moving from Ningbo to Shanghai, there came the American Presbyterian Mission Press, The Commercial Press and the Tousewe Arts and Crafts Press in 1864 by the Jesuits in Shanghai.

“Therefore, typography design and illustration art in Shanghai has always shown a good mix of Chinese traditional painting and a Western style,” said Jiang.

Illustration from a Chinese textbook (1908), The Commercial Press

The golden period of illustration in Shanghai came from the early 1980s to the late 1990s. Besides narrative ones, there were also commercial illustrations on packages, medical illustrations in text-books, fashion illustrations for designer events and concept art.

“Today, with the spread of the Internet and the other computerized means of art, hand-drawn illustrations has been gradually replaced by digital design or multimedia collage,” said Jiang. “It gives me the urge just to have them recorded before they finally go into the landfills. I hope people in the future can understand what makes Shanghai Shanghai in the modern days by flipping through my books.”