Sheridan's revenge tale goes beyond the frontier

For Taylor Sheridan, the West is still alive with frontier tragedies and genre thrills, even if hopelessness has moved in and blanketed the land.

“Wind River” makes it a kind of trilogy for Sheridan, the writer behind the West Texas neo-Western “Hell or High Water” and the Mexican border drug crime drama “Sicario.” In “Wind River,” he shifts to a Wyoming Native American reservation and behind the camera, but the atmosphere is still rich and familiar: big open spaces with misery all around.

Whereas the Oscar-nominated “Hell or High Water” had a bright, comic punch, “Wind River” is more in the heavily somber register of “Sicario.” When one father who has lost a daughter consoles another, he advises him to confront the heartache head-on: “Take the pain.” It’s something of a mission statement for Sheridan, whose neo-Westerns are filled with deeply burdened men making painful sacrifices.

Sheridan’s latest (his second time directing following the little-seen 2011 horror film “Vile”) is set around the Wind River Reservation in a wintery Wyoming where, as one character says, “snow and silence are the only things that haven’t been taken.” The reservation, shrouded in violence, drugs and poverty, is an ominous place.

It’s there that Corey Lambert (Jeremy Renner) discovers a freshly frozen body five miles (8.05 kilometers) into the mountains. He is a fish and wildlife agent who spends most of his time defending livestock by shooting predators with a rifle. Mountain lions nabbing cattle is what brought him, by snow mobile, to the remote crime site. The body, an 18-year-old Native American girl named Natalie (Kelsey Asbille) is barefoot, despite the snow and the cold, and she’s been raped. Her lungs, Lambert guesses, eventually froze and burst as she fled from miles away.

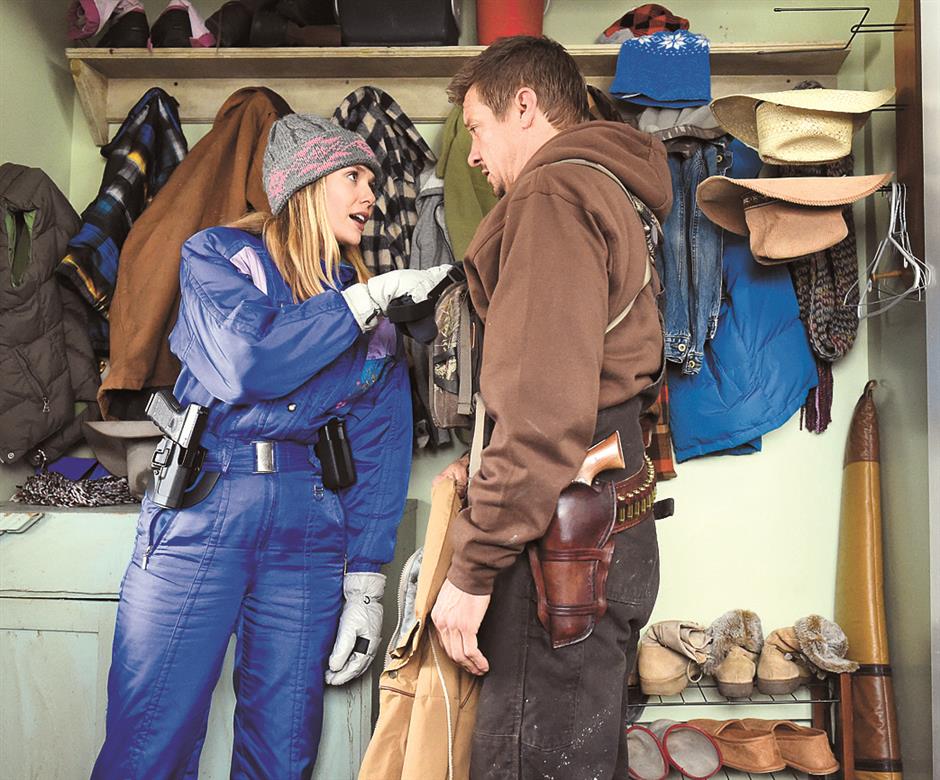

Jeremy Renner plays a fish and wildlife agent in a Wyoming Native American reservation in the film “Wind River.”

The investigation, though, is for the FBI. The agency is so thin in rural Wyoming that it dispatches an agent from Las Vegas: Jane Banner (Elizabeth Olsen) who lacks even a good enough winter coat. But Banner quickly shows her strengths and intelligently conscripts Lambert, an experienced tracker, to aid her.

The dead girl is revealed to be the daughter of a close friend of Lambert’s (Gil Birmingham). Birmingham, whose too-brief performance is one of noble weariness, is one of many Native Americans who populate the cast and lend “Wind River” both excellent acting and ethnic authenticity. When the police visit the family’s home, they find a broken household. An opened door reveals the guilt-ridden mother bloodily slashing at her wrists. The door, bizarrely, is simply closed.

Though Sheridan’s control of the tale is, up until now, fairly total, the sense that he is overplaying his hand begins to set in. He keeps opening doors and closing them too abruptly. The detective work continues, at first angling toward nearby drug-dealing tribesmen. But Lambert’s past (he is the father, now divorced, who also lost a teen daughter) is where the film gradually centers its emotions, and Renner, gives one of his finer performances.

Elizabeth Olsen as an FBI agent to investigate the murder case in the film “Wind River.”

But instead of plumbing deeper into the lives of those on the reservation, the gripping, solidly built “Wind River” begins to go wayward in its tracks. The over-the-top showdown finale comes largely out of the blue after clues lead Banner to a nearby oil digging crew. “Wind River” turns into a revenge tale where we only meet those worthy of vengeance just as their time is up. And, as in “Sicario,” women characters like Banner are welcomed into Sheridan’s film, but are steadily edged out.

Still, no one will confuse “Wind River” for anything slipshod. Its densely colorful dialogue and powerful sense of place make Sheridan a singular talent, with, hopefully, more directing in front him.