The light of his life: salvaging an old craft

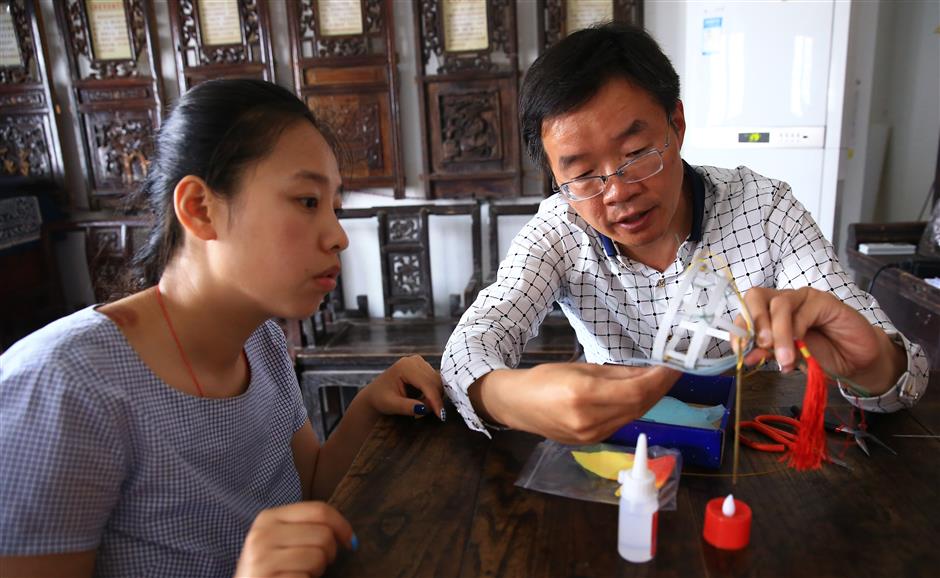

Zhang Juntao and his sister Zhang Junli discuss the intricacies of a lantern.

Lanterns, those quintessential symbols of Chinese culture to many people around the world, were once always made by hand. That art is dying. The skill used to be passed down from generation to generation. Zhang Juntao at first seemed to be about to break that chain.

He was supposed to be the seventh generation in his family to make lanterns by hand, but the Henan Province native instead chose to go into the insurance business. Fortunately for folk art, he had a change of heart.

Zhang, 46, and his sister Zhang Junli are now trying to save the nearly lost art of handmade lanterns.

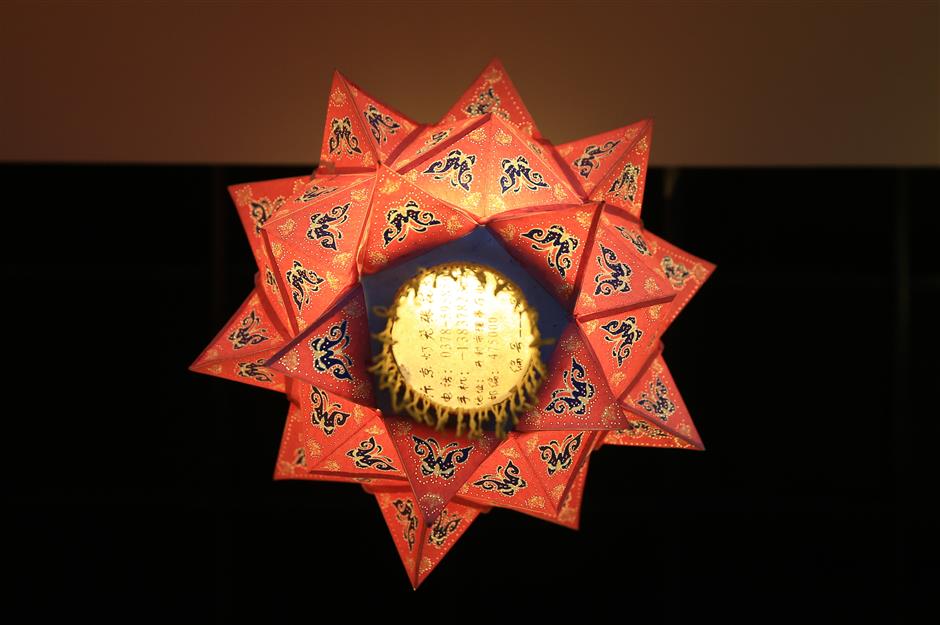

His family workshop is called Jingwenzhai, which means “room of respecting etiquette.” It is committed to reproducing the style of lanterns that once prevailed during the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127). In that epoch, the Zhangs’ hometown of Kaifeng was called Bianjing and served as capital of the dynasty.

“Lanterns started to play a big part in daily life more than 1,000 years ago, especially during the Lantern Festival, which developed into a carnival in the Song Dynasty,” says Zhang, who was recently in Shanghai for a course at the city’s Institute of Visual Arts. “I want people to appreciate their beauty, even though we don’t need their function of illumination anymore.”

Before taking over the family business in 2010, Zhang worked as a financial manager in an insurance company. It provided high income and bright prospects for a long career.

Zhang figured he might help his father financially with the family lantern-making business, but he wasn’t interested in becoming a craftsman himself. That changed when his father died in 2010.

“My father seemed to know that he didn’t have much time left,” Zhang says. “He had a serious talk with me before dying. He pleaded with me to take over the family business and help keep the art of lantern-making alive.”

Duty called. Zhang quit his job. A year later, he decided to move out of the family’s old courtyard house and turn it into a lantern museum. Jingwenzhai was started from there as well.

The museum, open to the public free of charge, now holds more than 1,000 lanterns in about 300 styles. Many are attached to rites or cultural traditions that date back centuries.

Some of the lanterns don’t have frames and are made from only paper or silk. That style of lanterns was used in prayers for prosperous harvests because the word “frameless” in Chinese, wugu, is pronounced the same as “food crop.”

Other lanterns are full of tiny holes pricked by needles. Those lanterns are usually made of thick, opaque materials and were used in windy areas to protect candles burning inside.

Some of Zhang's frameless lanterns are made only from paper or silk.

The museum traces lantern stories and functions, as well as the history of the Zhang family.

According to local Kaifeng chorography, the family can trace its roots back to Zhang Taiquan (1740-1806), who became a master of lantern-making in his youth. Government offices all ordered their lanterns from him, from palace gate lanterns to small indoor lanterns.

The family’s fortunes peaked in 1901, when the business was managed by Zhang Hong (1839-1904). When Empress Dowager Cixi and Emperor Guangxu visited Kaifeng, Zhang’s lanterns were hung in their temporary imperial quarters. The royal family said his lanterns “had the charm of those in the Forbidden City” and gave the family the enduring title “Lantern Zhang of Bianjing.”

The museum receives more than 10,000 visitors a year. “Once an old man came to the museum and nearly broke into tears when he saw one of the lanterns,” Zhang recalls. “For nearly all his life he said he had been searching for a lantern made of Xuan paper, which is folded on the surface and has gradient-style coloring. The lantern reminded him of his childhood.”

In the 100 years after Zhang Hong’s death, lanterns were transformed from utility products into works of art. That narrowed the market, leaving lantern-making a career that seemed limited and unprofitable.

“My father felt that pressure,” Zhang Juntao says. “It was difficult for him to recruit apprentices. He tried very hard to create new types of lanterns, using modern technology, such as lanterns with music or with robots. He thought that might revive interest in the art form.”

Indeed, Zhang and his sister spend a lot of time trying to embed the old tradition into contemporary consciousness. They have collected traditional patterns from all over the country and compiled them into a book. To date, they have found more than 60,000 patterns, and the search is continuing.

“It’s not easy,“ Zhang says. “The patterns are not off-the-peg, but come from wood blocks. We have to replicate the patterns with scanners and other machines.”

Many of the patterns, created hundreds of years ago, are unique in detail and delicacy.

“The patterns themselves are treasures,” says Zhang. “They embody the talent and skill of ancient people. I would like to see them revived through our lanterns.”

Zhang and his sister regularly visit schools to teach children how to make lanterns, using traditional ways of painting and even recycled materials. He said he hopes that some children will be inspired enough to consider becoming craftsmen some day.

“My father devoted his whole life to lanterns, and now it’s our turn,” Zhang says. “It is more than just a family business. It is precious cultural heritage that we can’t afford to lose.”

Some of the tools and frames used in making lanterns