Meteorite hunters looking to strike gold

They roam Morocco’s southern desert, braving the searing heat to scour the undulating sands for bounty fallen from the sky.

These celestial treasure hunters are searching for meteorites to sell on a burgeoning international market.

Equipped with a “very strong” magnet and magnifying glass, retired physical education teacher Mohamed Bouzgarine says that discoveries “can be more valuable than gold.”

The price “depends on the rock’s rarity, its shape and its condition,” the 59-year old said. “Rocks coming from Mars are very expensive, sometimes as much as 10,000 dirhams (around US$1,000) per gram.”

Bouzgarine stops in front of a hollow, hoping it will be a crater from “very long ago” by extraterrestrial matter.

“It’s a first sign,” he said, ready to get down to work, in the township of M’Hamid el Ghizlane.

For four years now, he’s been sifting rocks in the sand, inspecting them for telltale signs of burn incurred during fiery journeys through the atmosphere. And while he is yet to strike it lucky, the success of some of his hundred or so peers provides the stamina to plod on.

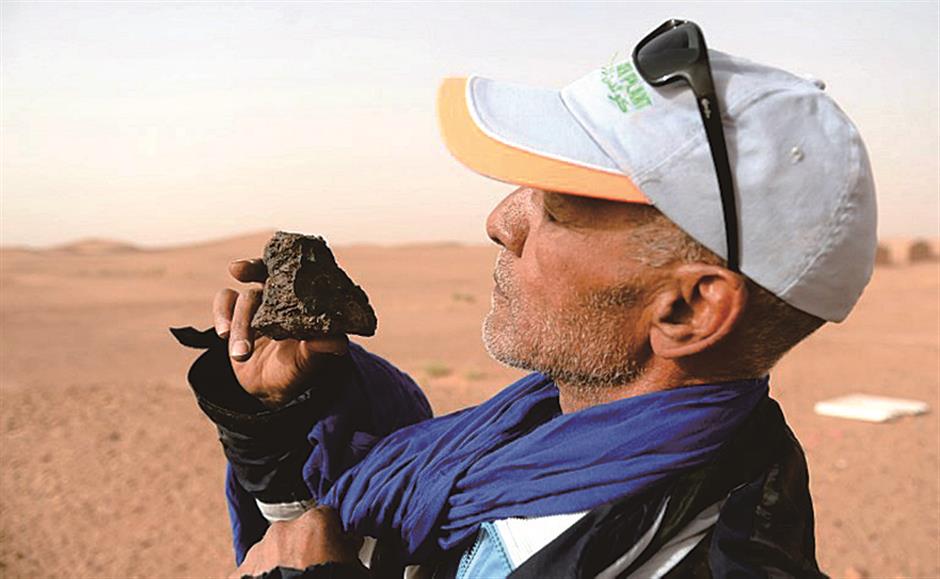

A meteorite hunter examines a rock near the oasis town of Mhamid el-Ghizlane, in southern Morocco’s Sahara desert province of Zagora.

Rich hunting grounds

Likewise, Abderrahmane, a 48-year-old paramedic, who is spending his vacation searching for meteorites.

Others “have made a lot of money. One meteorite hunter found and sold 600 grams for 7,500 dirhams per gram,” Abderrahmane revealed.

“From the 2000s, all the nomads started to look for rocks.”

A few foreign specialists are also drawn to the quest for extraterrestrial fragments in the desert landscapes of Erfoud, Tata and Zagora.

These parts of southern Morocco are rich hunting grounds. The wind uncovers meteorites and their black hue is easy to spot against the near-white sand.

“At least half the scientific publications on the subject are made on the basis of meteorites collected in Morocco,” said geochemist Hasnaa Chennaoui Aoudjehane, who teaches at Casablanca’s Hassan II University.

“Desert zones are favorable to the accumulation of meteorites. There is no vegetation and the risk of alteration is low.”

A meteorite hunter searches for rocks near the town of M’hamid el-Ghizlane, in southern Morocco.

For scientists, these rocks harbor valuable information about the formation of the solar system 4.5 billion years ago, as well as the planets and their internal composition. One in every five meteorites is valuable.

Demand from scientists and specialist brokers has raised prices and inspired meteorite hunters.

Unlike other countries, where the state stakes a claim, there is no legal framework governing discoveries in Morocco, so it’s a case of “finders keepers.”

While several meteor showers have occurred in Morocco in recent years, a bonanza known as the “black beauty” was the most lucrative. In 2011, fragments of this Martian landing fell in southern Morocco’s Tata region, setting in motion a scramble that saw 7 kilograms of fragments recovered. The haul fetched prices of between US$500 and US$1,000 per gram.

Back on the desert plains, it can be frustrating work, requiring a lot of patience.

Twenty days into his “holiday,” paramedic Abderrahmane has been “searching for fragments” without finding anything of note, he says.

But he remains undeterred.

“It is a question of luck — it’s like playing the lottery,” he smiled.

And he knows how he will handle a major find.

“The sale is made discreetly — it is necessary to get the vendor’s confidence,” he said.

Transactions are also made online, in specialist forums and even on classified advertising sites.

The most valuable finds are sold at auctions in Paris or New York.

“What one finds in the (local) souks are just odds and ends,” said Abderrahmane.

And there’s not much money to be made at the bottom end of the meteorite sales chain.

Slimane, an old man with a white beard and blue turban, sits under a tent in a souk in M’hamid, surrounded by colored fabrics, outdated jewels and old coins. He dips into a leather satchel, retrieving some rocks accumulated over the years.

“But they’re not worth much,” he confessed. “I have not risen above penury through rocks.”