To the power of two

When Ma Peiqing, 89, and Tan Dao, 95, joined the design office of Shanghai Turbine Plant in the 1950s, the newly established People’s Republic of China just started to develop its heavy industry. The then Czechoslovak Socialist Republic sent engineering experts to China to instruct local plants and firms.

They moved their families to Shanghai and brought with them turbine blueprints and other materials.

Ma and Tan worked with them from late 1952 to 1957, Ma studying steam turbine design while Tan translating written material into Chinese. They say that they want to find the offsprings of the Czech experts.

“I remember the names of the three Czech experts — but in Chinese only,” says Ma. “They were all with Skoda Electric. One was called Ke Lanmu, who was responsible for design, another Ye’er Masha, responsible for quality control, and Ha Te for technology improvement. I mainly worked with Ke Lanmu.”

Ma recalls that Ke Lanmu stayed in Broadway Mansions in Hongkou District and went to the plant, which was in today’s Minhang District, about once a week to give lectures to the Chinese engineers and help them with design.

“He was a guy who stuck strictly to the blueprints,” Ma says. “Sometimes I would ask him why it would be like that and how the theory behind it worked, he would answer sternly, ‘just do according to the print.’ Despite that, he was actually a lovely guy.”

Ma Peiqing (left) and Tan Dao recall the days back in the 1950s when China was developing its heavy industry.

The three experts spoke mostly German, with Ke Lanmu the only one understanding some English. Ma, who graduated from Xiamen University, spoke fluent English, so his team leader asked Ma to communicate with Ke Lanmu and find out what he needed for his life in Shanghai.

It turned out that the experts were fond of woollen goods.

“It seemed that the woollen products in Shanghai were much cheaper than those in Czech, and they would buy cases of them to send back,” Ma recalls.

Life for the experts in Shanghai was not all about work. The plant would organize events, such as dance parties and short trips, so that they wouldn’t feel bored.

Ma often helped arrange the trips, finding the best accommodation and dining for them and accompanying them to some places, such as Wuhan and Hangzhou.

“It was like I gained some advantage working with them,” he jokes.

As a translator, Tan worked more with blueprints than with the experts themselves. But he had never studied the Czech language, only Russian, which he taught himself in the early 1950s.

“I made good use of the period to study Russian with the help of textbooks and dictionaries in a bookstore. I have never been to college, and this period of self-teaching was my college,” he says.

Engineers and experts from the then Czechoslovak Socialist Republic were warmly welcomed upon arrival in Shanghai.

Tan started to learn the Czech language after he was tasked with translating the blueprints. Meanwhile, a student who had studied in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was sent over from Beijing to give them language training. Although it lasted only a week, Tan managed to grasp the basics of the language.

“Both belonging to Slavic languages, Czech and Russian had quite a lot similarities in vocabulary and grammar,” he says. “During our time, many people learned foreign languages that way. The secret is that you just keep learning and never stop.”

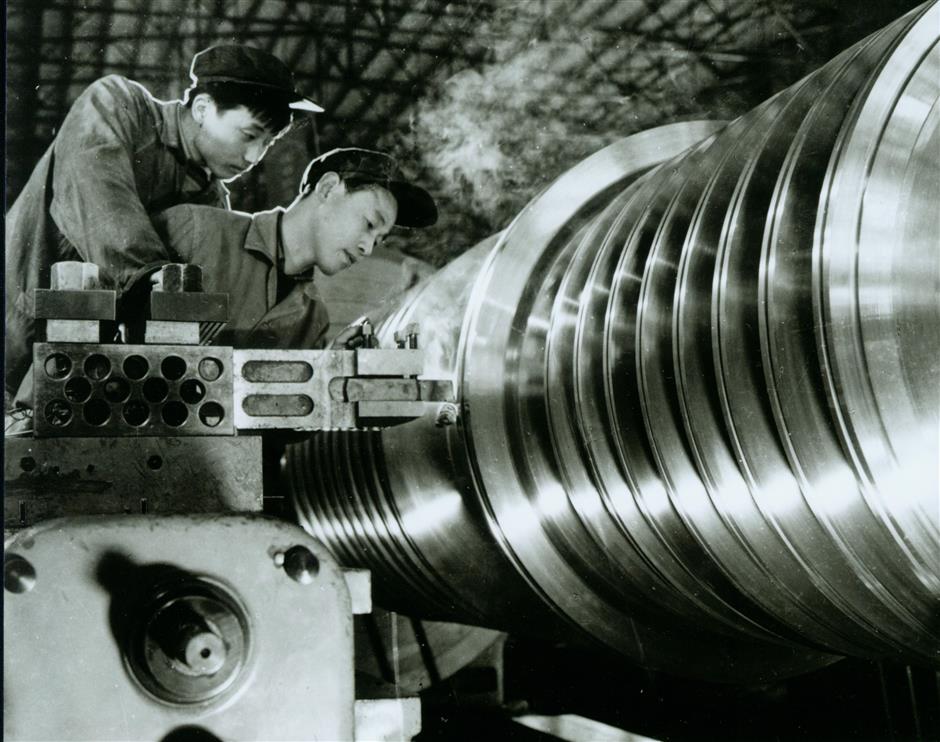

With the hard work of both Chinese and Czech experts, the turbine plant managed to produce the very first 6-megawatt turbine in China in 1955, a breakthrough in the country’s industrial history.

Development did not stop after the Czech experts went home. The plant made more powerful steam turbines over the next 50 years, which were widely used in military and nuclear power plants.

Ma and Tan parted during the “cultural revolution” (1966-76). While Ma continued his work in the design office, Tan was dismissed from the office and became a Chinese language teacher at a vocational school.

“I was always interested in literature, and this job gave me a lot of time to immerse myself in the library, reading all kinds of books I could reach,” Tan recalls. “I see this period of time my second college study.”

After that turbulent period was over, Tan was transferred back to the design office and became Ma’s colleague again. This time he was responsible for translating American material into Chinese and, while no American experts came to China, Ma led a team and went to the United States to study at Westhouse Electric.

After retirement in the 1990s, the two moved to downtown Shanghai, living not far from each other. While Ma enjoyed a life of leisure with his wife, the Tans went on an around-the-country tour. He also wrote novels and drama scripts.

Ma and Tan keep close contact with the plant, which has now been merged into Shanghai Electric, and still pay attention to the development of power generation in the city.

“Looking back to our past, with the help of other countries like the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, the former Soviet Union and the then United States, as well as our own efforts and creations, we managed to develop the Chinese power generation from zero to top,” Ma says.