Expat coaches serve up tennis skills

They’re good tennis players and love to win. But it’s an even better feeling when they see their students win. They are the tennis coaches whose serves, backhands and forehands we try to emulate. Let’s meet some expat tennis coaches in Shanghai, learn about their stories and follow their instructions.

Daridge Saidi coaches his students at a tennis court in the Pudong New Area.

Daridge Saidi

The tennis court lights come on as dusk falls. Daridge Saidi, a young man from France, calls his group of four children together.

The girl and three boys stand in a line behind several colored obstacles. With a racket in their hands, they bend down slightly, watching the balls about to be thrown toward them by their coach. Then they circumvent the obstacles, catch the balls and serve.

“The girl can understand English well. Sometimes I tell her what to do and she passes on my message to the rest of the kids,” said Saidi, who is in his late 20s and a coach at Love Tennis Academy in the Pudong New Area.

“Right behind my childhood house there was a tennis court, so my father just took me there to try. And I liked it and was pretty good at it. I kept playing every day and it just became my passion,” said Saidi.

Born near Marseilles, Saidi moved with his parents to Paris when he was about 14. He played tournaments and, from the age of 17, gave lessons to help children improve skills.

He spent his freshman and sophomore years at Paris 13 University but then had to decide to either quit school and become a professional tennis player or stop playing tennis and focus on his studies.

But US universities allowed him to do both, so he continued to pursue his degree while playing tennis at Eastern Kentucky University, gaining a master’s degree in sports science.

“The most joyful thing of playing tennis brings to me is to win, definitely. And the most joyful thing coaching tennis brings to me is to see others improve and win. Seeing others win competitions under my guidance is even joyful than myself winning tournaments,” Saidi said.

In the US, he coached and mentored young people with physical or mental disabilities at Kentucky Adapted Physical Education School.

“For those kids, being able to run or lift something up was a great success. Those kids were helped to do something which looked so simple to us, but to them it was a big deal. After every session when I went home at night, I felt how lucky we are to be healthy. I realized the daily problems I had were actually nothing because those kids were born like that and they had to fight,” Saidi said.

Saidi said he noticed that different countries have different tennis cultures.

“In France there are many tournaments and in the US people also compete a lot, whereas in China people want their kids to have a pretty forehand or a pretty backhand, but I don’t think there are many tournaments. So it’s hard to get that frame of mind going. You know, because when you practice and when you play a match, it’s completely different,” Saidi said.

Asked what kind of people have the most potential to become good tennis players, Saidi said: “For kids, the first thing is that they need to be coordinated. When they are 4 or 5 years old they have to start playing some ball games, like through playing soccer they know how to use their feet. When they did that since they were young, then when they get to 10 or 12 years old, usually they are pretty good at coordination.”

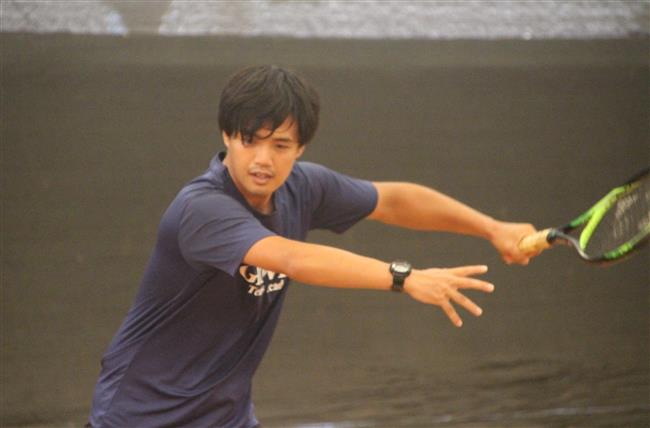

Daridge Saidi plays in a tennis match.

Hideyuki Tahara & Ryo Hamano

Ryo Hamano from Japan smiles as he relates how he joined the Osaka police school because he thought policemen were handsome. He later quit, finding that being a policeman really wore him out.

Hamano is now a tennis coach at the Glowing Tennis Academy, a Japanese sports coaching and consulting enterprise in Shanghai.

Hideyuki Tahara, also a coach, is general manager of the school.

“Being a tennis coach in Shanghai, I am happy to see my students improve and act well. But the job also bothers me as it’s a very energy-consuming job. I have to take health products like vitamin C to keep myself fit,” said Tahara, who spoke in Japanese.

Tahara is from Oita Prefecture, Kyushu Island; Hamano, also hailing from Kyushu Island, is a Fukuoka native.

Tahara didn’t begin playing until he was a senior high school student, but his zest for tennis was no less than peers who already had experience.

“My interest in tennis developed as I played, so I went to study at a professional sports school in Tokyo,” said Tahara.

At the sports school, Tahara, while being trained as a tennis player, also studied nutrition and physical fitness.

After joining a Tokyo tennis company in 2001, Tahara learned how to teach both teenagers and adults from a leading coach with 30 years’ experience. Later, Tahara came to China and began coaching tennis and running a tennis school at the suggestion of an acquaintance.

A group of students at the Glowing Tennis Academy

Both Hamano’s parents play tennis well and they taught him how to play when he was a Grade 1 student at primary school.

Hamano won second place at a national elementary school student tennis competition in Fukuoka and qualified for the tougher Kyushu Island competition.

Having noticed their son’s gift for tennis, Hamano’s parents sent him to learn from Yasumasa Mouri, a renowned coach in Japan. The coach is a left-hander and Hamano learned his left-hand tennis playing strategy and techniques from him.

“Since most people are right-handers, being a left-hand tennis player, you have advantages,” said Hamano.

To further improve his skills, Hamano later entered Yanagawa High School, a school famous for its tennis achievements. During the period, he won second place at the singles in the Kyushu competition and the doubles at the JOP tennis competition. Hamano joined Glowing Tennis Academy in 2013.

When talking about the differences between China and Japan, Hamano said: “In Japan, score and rule announcements during a contest are spoken in English, whereas in China, they are usually spoken in Chinese.”

“Children with the potential to be a tennis player go to a public sports school in China. But in Japan there are no public sports schools for children. Children who want to play tennis usually go to a club or a training center to learn,” Tahara added.

Hideyuki Tahara gets ready to serve.

Ryo Hamano in action