Breeding righteousness through a book

Yang Baiwei

Cao Zhengwen

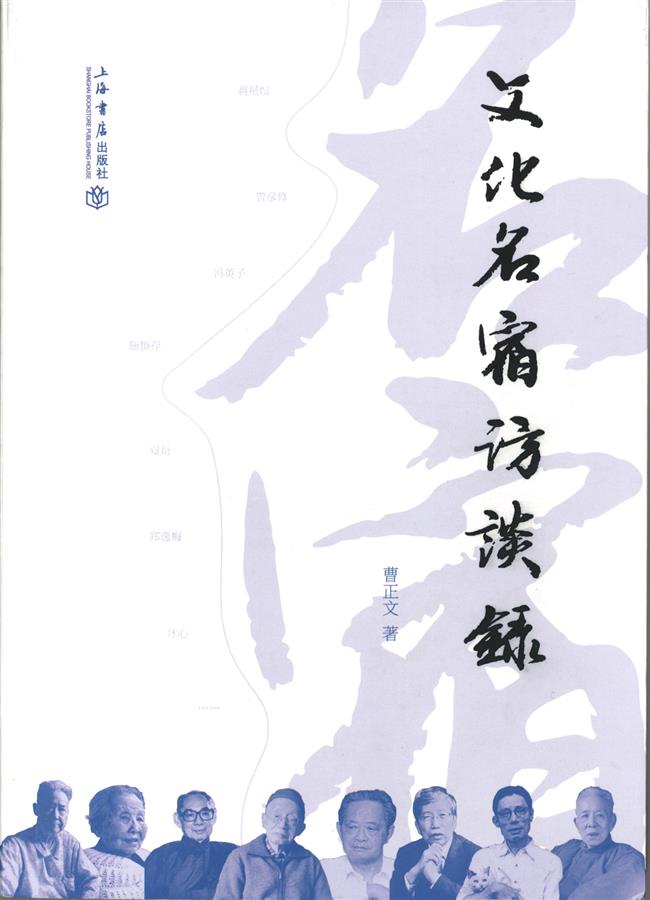

A Record of Interviews with Cultural Icons by Cao Zhengwen

Nothing entertains us better than reading a book, says a renowned Chinese writer. When Bing Xin (1900-1999), a pioneer of children’s literature in modern China, expressed this belief in 1987, she was gazing upon an era when entertainment news was on the rise across the globe.

“Entertainment news has increased, which is fine, but I believe the most pleasant thing about life is to read books,” she told Cao Zhengwen, editor of the “Joy of Reading” section of the Xinming Evening News.

Cao’s interview with Bing Xin at her apartment in Beijing took place about two years after American educator Neil Postman published his book, “Amusing Ourselves to Death,” which criticized televisions for diluting rational thinking that was typical of typography.

To encourage more people to read, Cao launched the “Joy of Reading” section in the Xinmin Evening News in 1986. During the 22 years when the “Joy of Reading” survived and thrived, he interviewed quite a few cultural figures and invited them to write for the newspaper. Bing Xin was one of them. Cao later sifted and edited the stories of their life as bookworms and critical thinkers into the book entitled “A Record of Interviews with Cultural Icons,” which was published late last year.

Thanks to Cao’s effort, today’s readers can have a rare glimpse into the spiritual world of typical Chinese intellectuals of a bygone generation, a world of simplicity, sacrifice and selflessness.

The book tells us not only how joyful they were in reading, but also how just they were in adversity. In other words, the book teaches us how to bring out the better part of ourselves as well as how and what to read.

One hardly understands today’s China — her value or her future — without knowing the spirit of personal sacrifice for societal good as embedded and embodied in righteous people like those recorded in Cao’s book. Though written in Chinese, the book is commendable as a necessary guide for anyone aspiring to be a China hand.

“When I was young, I held those righteous scholars and writers of modern China in high respect,” Cao told Shanghai Daily. “So I tried my best to interview them when I was responsible for the ‘Joy of Reading’ section. I had collected a huge stack of notebooks documenting their profound knowledge and upright characters.” For example, Qin Mu (1919-1992), a renowned writer, was quoted as saying that only an upright person can write a good article from a candid approach. Wang Yuanhua (1920-2008), a literary critic, said he liked the works of Lu Xun (1881-1936) because he respected Lu Xun for his critical thinking.

“Of Cao’s nearly 70 books, this one is not that bulky, but it’s significant in that it has faithfully recorded and revealed the truth of many cultural events through his interviews,” said Yang Baiwei, editor-in-charge of the book and deputy editor-in-chief of Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House. “The book tells readers around the world about the integrity, courage and profound learning of modern Chinese literati.”

And it’s more than about literati. Their stories, told in the plain language that’s a trademark of Cao’s writing, reflect a larger picture of Chinese culture that breeds righteousness.