Dependence on smartphones normal, but also just a little bit frightening

The speed at which I have become dependent on my smartphone to take care of literally everything in my life became abundantly clear over the past week when I moved apartments. It was both great and, if I’m honest, a little bit frightening.

Before moving this week, I lived in the same place for about two years, and in that time built up a web — excuse the pun — around my life where numerous smartphone apps, while giving the illusion of freedom and choice, tied me to my physical address as if with chains.

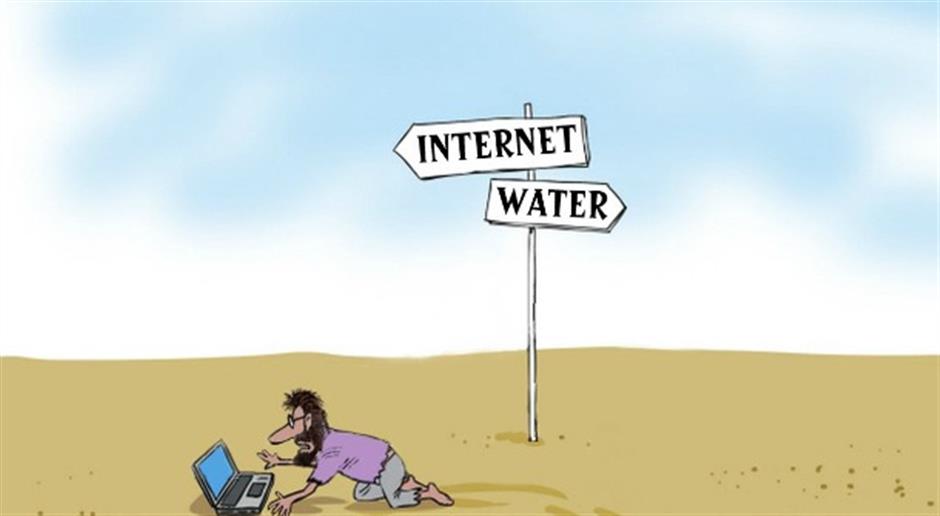

Food, water and other essentials, plus all the amazingly useless gadgets and toys I sometimes buy online, all formed an invisible but strong link between my phone and my physical address.

Whenever I couldn’t be bothered heading out for dinner — and since I didn’t cook in the old place — I would order waimai (food delivery) from probably a list of five favorite restaurants. All it took was a thumbprint to get the chain of events going that would eventually lead, about half an hour later, to a delivery person knocking on my door with a bag in hand.

Water is another must-have that I decided should be ordered online to save me lugging 5-liter bottles of water from the supermarket back to my apartment. Again, just a thumbprint was all it took.

The list goes on.

I never realized how much technology helps out, while at the same time relying on a fixed place in the real world to turn it all into reality.

That is until I moved apartments over the past week.

All of a sudden that safety net I had built up around myself of small restaurants and water suppliers and countless others came tumbling down.

While I was between places, of no fixed abode as it were, I felt in limbo. My phone all of a sudden felt useless.

Will courier and food delivery guys be able to find my new little apartment on the sixth floor of one small part of my new xiaoqu (community)? Are my favorite restaurants close enough to keep delivering to me? When I order things online that are delivered while I’m at work, where will they be placed? Where are my new kuaidi (delivery) lockers?

And so, as it turns out, this week I still haven’t taken the leap. I still haven’t begun slowly piecing my digital life network back together, even though I’ve now been living in my new place for a week.

In terms of ordering waimai, a bunch of other people’s physical addresses bound me to my life of habits. A quick browse of those five go-to small restaurants I mentioned from whom I like to order takeout were all now around 10 kilometers away from my new home. Surely I can’t expect some poor food delivery guy to trek so far, and even if he was willing I’d probably be racked with guilt during every bite.

That’s led to a lot of adventures, like finding things to eat in my new community (I would have done that anyway, but maybe at a slower pace!) and locating, perhaps quicker than usual, supermarkets nearby that I can lug bottles of water home from.

It’s not like I couldn’t just simply update my address in the dozens of apps I use — that’s easy enough. I guess the big thing I’ve discovered while coming to this realization is that no matter how fast technology and online services develop around us, we still exist in the real world, among the bricks and mortar. Our real-life locations in the world are still such an important factor of our ever-more connected world.

This week has helped me learn that, and given me the chance to step back and take a deep breath.