Zhao: A historical insight into Sino-US cooperation

When I was deputy mayor of Shanghai, I was in charge of the development of Pudong. Pudong, on the eastern side of the Huangpu River that runs through the heart of Shanghai, used to be a huge expanse of uncultivated plots and rice paddies.

Pictures taken of Pudong before its opening-up show waterlogged residential homes during rainy spells. That's why Shanghai citizens quipped then that they would choose a bed in Puxi (the West side of Shanghai) over an apartment in Pudong, because Pudong was both inaccessible and uninviting.

Zhao Qizheng (left) meets former US President George H.W. Bush.

In the wake of China's reform and opening-up, especially under China's late leader Deng Xiaoping's direction, Shanghai began developing Pudong from 1990. Twenty-nine years have passed and what a difference time has made!

A business portal in the United States once published two photos of Pudong before and after its opening-up, together with comments by American netizens. One post said that the Chinese are good at architecture, and the Shanghai Expo (2010) was comparable to a world architecture exhibition. Another post countered this view by saying that edifices in China are erected at the expense of the environment. Look at the black air clouding their skyline, the author said. This critical observation prompted a reply from a third commentator, who pointed out that what was thought to be "murky air" was actually a night view of Shanghai. The sharp contrast in these comments hints at the diverse American public opinion held about Pudong's makeover.

In the early days of Pudong's development, most pundits in the West perceived this endeavor as more a slogan than some real action on the ground. One of them, the expert on currency and winner of Nobel Prize in Economics Milton Friedman, was sarcastic. He lampooned Pudong’s development as an attempt to build a modern Potemkin village.

Around that time, Dr. Henry Kissinger made multiple visits to Pudong, which he saw as a window on China, and we held discussions about the development of Pudong and global environment. Initially I showed him the rendering of a new Pudong on the map -- then architecture models -- and eventually I took him to the Oriental Pearl TV Tower and from there we peered at the construction sites and towering cranes that cluttered our view. At this point Dr. Kissinger remarked to me that he became convinced the development of Pudong was for real instead of just sloganeering. He was the first American to say so. History has proven that he is prescient.

Pudong used to be a corner unbeknownst to the world. When I accompanied then American Secretary of State Warren Christopher on his visit to Shanghai in 1994, he looked across the Huangpu River toward what was to become the Lujiazui area and asked: "World Bank says Shanghai is home to 17 percent of the world's construction cranes, is that right?" I replied that I did not have the report but was myself astounded at the sheer amount of crane activity in Shanghai.

In the subsequent years, President George H.W. Bush also came for a visit and I gave him a briefing about the planning model behind the would-be Lujiazui financial zone. The president asked about the size of investment and construction in Pudong. Upon hearing my answer, he said he would love to come and invest if he were younger. These were the observations by two great American statesmen.

This was also the moment when some observers in the US became interested in studying Pudong. The Boston Sunday Globe, a reputable publication, ran a special report on January 7, 1996 entitled "Should we fear China?" This is the earliest form of “China threat theory” as I know it, but the headline was still framed as an open-ended question, not a rhetorical question. The key argument of the report boiled down to the assertion that China may well become an economic powerhouse as well as a political and military giant, and as it happened, should Americans watch from afar with trepidation?

In case you are wondering, here are some economic figures from that period. The GDP of the US was US$8 trillion in 1996 while Japan's stood at US$4.7 trillion. By contrast, China's GDP was a mere US$860 billion, a tenth of the US's and a fifth of Japan's. I thought then that the US newspaper's coverage of Shanghai was a little paranoid, albeit tinged with a sense of humor. Look how early whispered talk of the “China threat” has grown into the "China threat theory" today!

Pudong's development is closely tied to the keen involvement of the US. Three world-class skyscrapers are now nestled in close proximity toward each other in Pudong. The Jinmao Tower, topped off in 1998, stands 420 meters tall and is designed by US architecture firm SOM. In 2008, Japanese investors hired KPF, also an American firm, to design the 492-meter-tall Shanghai World Financial Center. The third, Shanghai Center, now the tallest building in Shanghai at 632 meters, was the work of Gensler, also a US company whose portfolio included Dubai's iconic Burj Khalifa Tower.

The three skyscrapers are a testament to American companies' success in China and also their design capacity. In a classic definition of global division of labor, American engineers took care of the skyscrapers' overall design. Their Chinese counterpart oversaw the structural designs. And the actual building was done by Chinese construction companies. These skyscrapers will last a century or two as a permanent monument to Sino-US cooperation.

During my term as vice mayor, Richard Wagner, then chief executive of General Motors, signed his name on an agreement to form a joint venture, Shanghai General Motors, to build cars in China. What began as a four-factory production now has expanded into eight plants rolling out cars like Buick, Cadillac and Chevrolet, with a maximum annual output of 4 million units.

In 2008, GM went bankrupt and after being bailed out by the US government, the car maker was back on its feet. SAIC, its Chinese partner, worked out a scheme where it would buy part of the beleaguered car maker's US-traded shares and sell them back to GM after it saw a turnaround in its fate. When GM's subsidiaries around the world were hemorrhaging money, the Shanghai venture was the only bright spot that was not just profitable but actually thriving.

There's another story, the story of Disneyland. I had the privilege of being received by Frank Wells, the former chief executive of Disneyland, on my visit in January 1994 to the US. I told Wells that Pudong was in the midst of a massive development drive and Shanghai would be turned into one of the most prosperous cities in China. He figured what I told him was attractive enough for one of the world's largest amusement park and resort groups. He immediately sent a team to Shanghai for a reality check and agreed to keep an eye on future development.

Tragically, his helicopter crashed and he died. In the US, the passing of a company's leader usually spells the demise of his signature project. But some twenty years on, Disneyland reopend communication channels with Shanghai and later invested US$550 million to build the Shanghai Disneyland. Despite a cap on the number of tickets sold in a day, the theme park recorded around 11 million visits per year. Now its operator is looking to expand it. Shanghai Disneyland is where the Chinese people flock to experience American culture.

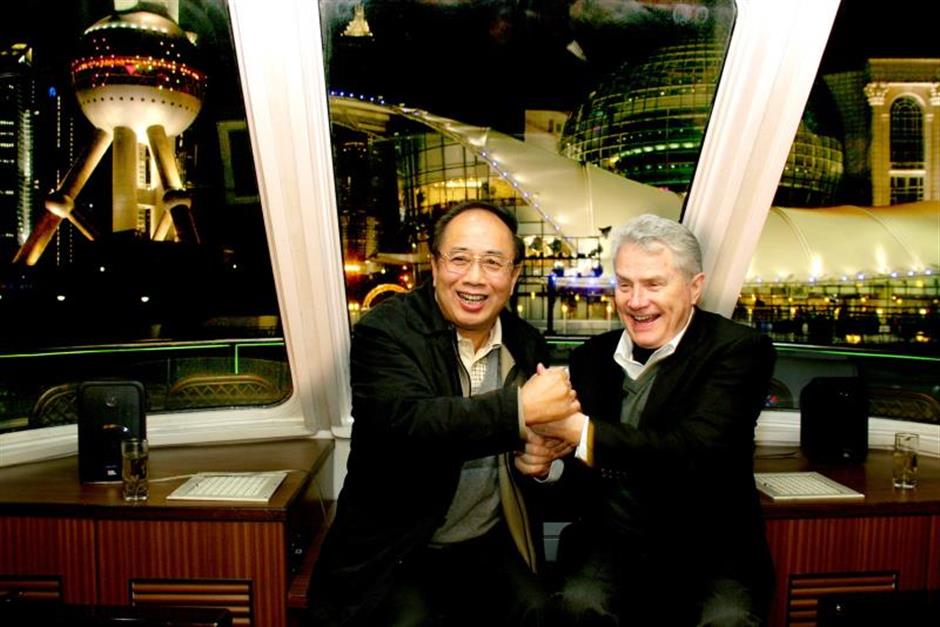

Zhao Qizheng (left) with international Christian evangelist Luis Palau

Now, another massive US-invested project is underway in Shanghai – the mega-factory of Tesla Motors. From the ground-breaking ceremony in January to the planned operation in October, Tesla will have a turnkey production line handed over to it within a year. In a similar tale of “Shanghai speed,” when we promised GM executives to finish construction of its Shanghai factory in a year, the Americans were skeptical that this massive project could be wrapped up in such a short period of time – only to be surprised even further that this job was completed one month ahead of schedule.

Weeks ago, American retail giant Costco opened its first store in Shanghai and saw another record set by the locals. Due to overcrowding and long lines in front of cashiers, Costco had to temporarily close down after half a day's business. Why was that? This incident definitely tells us less about the so-called Clash of Civilizations, as proposed by political scientist Samuel Huntington, than about the fact that American-style management appears to be ill-suited to local conditions.

Given my own experience, "forced technology transfer" was hardly in evidence over the course of Sino-US collaborations in these aforementioned areas. Up until today, the Chinese shareholder of Shanghai GM continues to pay certain sums of licensing fees for every car that rolls off the assembly line. This means that the issue of intellectual property was already factored in during the early days of the new venture. Maybe there are other cases involving US investment, but as far as I am concerned, American businessmen are mostly happy to sign agreements with us; they are not forced into these partnerships.

Here's a final story. In 2000, I gave a speech titled "Americans and Chinese in the eyes of the Chinese" at the National Press Club in Washington D.C. From the time the first American commercial ship arrived at Guangzhou, known then as Canton, in 1784, Chinese people were fond of the Americans, who were considered to be more generous, straightforward and easygoing.

These were some of past dealings with the US as a former official. I hope these accounts could let Americans know a bit more about China. I hope the US (which is pronounced as "mei guo" in Chinese, literally "the beautiful country") will remain "the beautiful country."

These were my stories, and they were mostly reconstruction of facts with little personal analysis. As things stand, we have to think what new stories are in store for the China-US relations going forward?

The author is former vice mayor of Shanghai (1991-1998) and former head of the State Council Information Office (1998-2005). Shanghai Daily staff writer Ni Tao translated this article from the Chinese.