Some of us see the world in a different light

Wang Hao, 26, enrolled at a driving school with the aim of getting a driver's license. As part of the process, he had to take an eye test. That's where his license hopes abruptly crumbled. The doctor told him he had deuteranopia, commonly known as "green color blindness."

"That was disappointing," he said. "Even though traffic lights appear to me as brown, grayish green and light yellow, I can still tell difference between one light and another."

Wang is not alone in his frustration. An estimated 5-8 percent of men in China and about 1 percent of women suffer from some form of color blindness. Many of them share their distress and experiences on social media.

Fushu Lab, a data journalism workshop at the School of Journalism of Fudan University, trawled thousands of online posts, including major social networking services such as Zhihu, Douban and Baidu Tieba, to form a picture of the lives of people with the deficiency.

Persons with color blindness experience different symptoms, depending on their insensitivities to different wave lengths of light. Those who have problems with green light might see the world in varying shades of blue, yellow and brown. Those with problems of the red spectrum see the world dominated by different shades of green. A smaller number can't process blue light, and even fewer people suffer total color blindness and live in a world that looks like a black-and-white movie.

More men than women suffer color blindness because it's caused by a gene on the X-chromosome. Men have only one X-chromosome, but women have two, which can offset the effect. There is no known cure for the condition.

In China, persons with color blindness are barred from working in dozens of fields, such as chemicals, archeology, the arts and sports. Those with red or green blindness aren't allowed to drive.

According to Fushu Lab, 62 percent of the netizens with color blindness found out about their condition when they took the requisite physical tests before college entrance examinations.

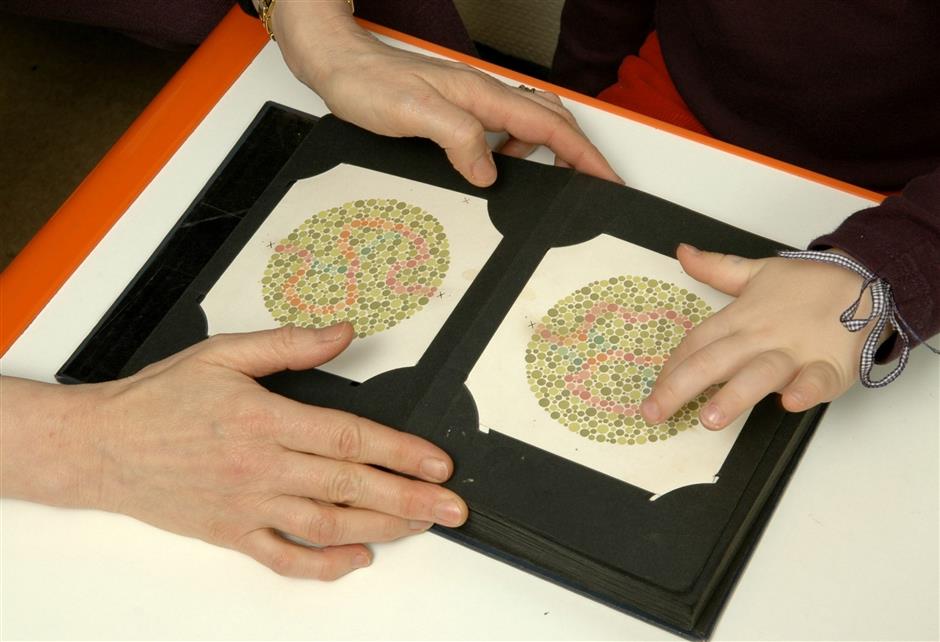

Wang was one of them. At that time, a doctor gave him a book in which dozens of pictures were displayed in small, colorful pieces like a mosaic collage. He was supposed to identify numbers in some of the pictures. He figured out two of them but got confused by the third and fourth.

"I had some inkling about a problem earlier than that," he said. "In high-school art class, my teacher told me that my color modulation was 'weird.' I couldn't differentiate shades of many colors. For example, I can't tell the difference between rose, pink and coral."

The journalism lab study found that about 17 percent of people surveyed found out about their color blindness as early as primary school, and 12 percent were diagnosed while in middle school.

A netizen with the screen name Minnie explained what a shock it can be. She related an experience she had during a physical exam in primary school.

"When I couldn't figure out a number in a picture, the doctor and students around me whispered, and I thought I had some incurable disease and was going to die," she said.

Students suffering from color blindness may also be prey to taunting and school bullies.

Fushu Lab found more than 100 users complaining online about being made fun of at school.

"I didn't mind being open about my deficiency, but some classmates would stick a random thing under my nose and say: 'Yo, what color is this?'" said a netizen with the screen name Bai. "It made me feel really bad."

According to Fushu Lab, test results showing the deficiency are sometimes met with skepticism or even anger. Some sufferers challenge the validity of the test itself.

"I have never felt that I had issues with colors until I had to identify those numbers in the test pictures," said an anonymous user on Zhihu, a Quora-like question-and-answer website in China. "I wonder if the test is really scientific enough."

The pictures currently used to test for color blindness are based on the Ishihara Test developed by Japanese professor Shinobu Ishihara in 1917.

Chinese oculist Yu Ziping (1920-2018) introduced the test into China, modifying it to suit the Chinese population. There were five test updates until 1997.

Despite the misgivings voiced by people with color vision problems, it hasn't been updated since.

Those with the deficiency have tried to find ways to thwart the eye tests, especially when applying for a driver's license.

One common ploy is to buy a color test book and memorize all the pictures, which is extremely difficult because one has to remember the pages as well. The other way is to cheat by wearing a pair of "color corrective" contact lenses that are available online.

According to a report last year, a man in the neighboring Jiangsu Province who was trying to pass the physical exam for a driver's license was seized by police for wearing such contacts, after the doctor raised the alarm.

The man was taken to a police station where he was "properly handled," according to the news account. No mention was made of what penalty, if any, was imposed.

In fact, members of the National People's Congress as long ago as 2011 proposed lifting the ban prohibiting color blind people from getting driver's licenses, but so far, no action has been taken.

Wang Chunlan, a doctor from Anhui Province who sits in the congress, proposed last year that color blind people be allowed to acquire C1 driving licenses, which cover cars that hold less than nine people and small trucks less than 9 meters long. She also recommended that study majors now off limits to them be restored.

"It is a cognitive error that persons with color vision deficiency can't see the red or green of traffic lights," Wang said in her proposal. "It is also unfair that such persons are rejected by some academic disciplines. The first scientist who studied color blindness, Briton John Dalton, had color vision deficiency himself and that didn't prevent him from being a distinguished chemist."