The flower lady of Zhongshan Park

The author, from Australia, is a member of Shanghai Writer's Association. She won the second prize of the 5th Shanghai Get-together Writing Contest, which just concluded last month. This story happened seven years ago.

I had recently left a place where spring was blooming, where the perfume of blossoming flowers filled the air. Near my house in West End, an inner-city suburb on the banks of the Brisbane River, there were garden walls and fences covered in jasmine flowers, which carry an especially rich aroma that seems to saturate the air on a warm spring evening.

Even though it was autumn in China, I smelled the same aroma one night as I was walking along the footpath towards the New Space-Time Ruili Hotel, where I was staying, in Zhongshan Park, which was part of the business district of Shanghai. The smell was at once so unexpected and so familiar that I had to stop. I followed the scent and discovered, behind a dividing hedge, a small Chinese woman standing beside a bicycle adorned with flowers. The larger bouquets were arranged around the seat and frame of the bicycle, while the basket at the front was lined with smaller bunches of jasmine blossoms. At first, the woman thought I would be interested in the larger, more expensive blooms at the back: the long-stemmed lilies, the red and crimson carnations, or the pink and yellow roses. So she laughed with genuine surprise when I leaned forward into the basket at the front of the bicycle, buried my face in the little bunches of jasmine and almost sang out with joy.

She giggled. I laughed as I emerged, my face tingling and bright. She said something in Chinese; I answered in English. I pointed at the jasmine.

Duo shao qian? I asked. How much?

Huh? she said, shrugging quizzically.

Duo shao qian?

She laughed again, I suppose at my terrible Chinese pronunciation. She said something. I imagined it was a price. I shook my head and held out my hands to convey: I don’t understand.

She repeated the same words and held up one finger, then five fingers.

I couldn’t tell whether this meant fifty, five or fifteen yuan. I responded by holding up ten and then five fingers.

She nodded, laughing. I said fifteen.

She said: Shi wu! Shi wu!

I repeated her Chinese with my awful Australian accent.

Shi wu? Shi wu?

She laughed so hard she had to bend over and slap her thigh.

Eventually, after much laughing and shrugging and slapping of thighs, the transaction was complete. I went back to my room and put the jasmine in one of the drinking glasses from the kitchen and placed it on the ledge in front of the window. I would perch on this ledge sometimes at the end of the day and watch the street gradually empty of pedestrians and motorists, until the flashing screen above the Cloud Nine shopping mall was switched off and a stillness that seemed unimaginable in the hectic business of the day settled over this part of the city. That night, as I perched on the ledge near the flowers, their perfume reminded me simultaneously of two places, the street where I lived in Brisbane, and the street where I now lived in Shanghai.

I bought flowers every couple of days after that. I still didn’t know the name of my flower lady, which was what I called her in emails back home. She didn’t know my name either. Perhaps to her I was the flower lady too. And though we communicated mostly through the silent international language of gesture and mime, over a short space of time, in this city full of strangers, she became something constant and familiar.

One Thursday just before 10pm, I sat on the steps outside Starbucks near her bicycle and watched her as she worked. It was quieter than usual and, despite it still being the National Day holiday week, business was slow. My flower lady wanted me to buy some flowers. But I had two full vases already in my room, and the only jasmine she had was an old bunch with drooping stems and falling petals.

I offered her some of my takeaway tea; she offered me the dying flowers. She refused my offer, but I accepted hers. I didn’t want to take the flowers for nothing so I gave her a few yuan, which made us both happy.

We were silent as she leaned against her bicycle and I sat on the steps, holding my tea in one hand and the rotting flowers in the other. Again, I thought of home. And suddenly I thought of hers too. I didn’t know where she came from or how far she’d travelled to arrive here, but sometimes I don’t know where I come from either, or even what that word – home – really means.

I didn’t carry a camera with me when I travelled; I took only my laptop and my instrument, usually a violin. So to remember that moment I began to compose some music that only I could hear on the stringed instrument I kept inside me for occasions such as these. Along with the music, I composed a vision in my mind, as I sometimes did – a virtual video clip, if you like – of my flower lady riding her bicycle up the street towards my house in Brisbane. She was smiling and waving as she cycled past gardens and fences and footpaths dripping with jasmine. Then, to make her more graceful as she cycled up the hill, I visualised her in slow motion. And suddenly I felt so free that I even gave her little wings, as she had given my mind and heart wings here in Shanghai so that they could fly more lightly in this concrete and neon and endlessly active world, through the gift of her flowers.

As she rode I lifted my violin on the corner of my street and played for her the melody of a traditional Chinese folk song called ‘Jasmine Flower.’ The music swelled as she reached the top of the hill. And lining the streets were my neighbors and friends, my family and my colleagues from Brisbane and here in China and from all over the world, holding up 10 fingers, then five, as they sang in honor of the jasmine flowers and the lady who sold them, in the echo of a plaintive Chinese melody: shi wu, shi wu, shi wu.

Outside Starbucks, my flower lady noticed that I was smiling and singing to myself. I didn’t know what she thought I was doing, whether she worried I was one of those crazy people who smile and sing in the street. She laughed again and hit her hand on her thigh.

I waved goodnight to her and said thank you in Chinese, xie xie, which in my Australian accent sounded like share share. I walked back to the hotel, trailing dead flowers as I went, up the stairs, through the lobby, into the lift, along the corridor and through the doorway of my room, shedding petals on the floor beneath me just as I had to shed the skins of my old dead selves whenever I travelled – so that I could arrive in a new place as vulnerable and open as a child might be in a land of giant and mysterious things.

In my room, a fresh bunch of jasmine was arranged in a glass sitting on the ledge, a fragile silhouette against the window, through which I could see the roads and neon and train lines extending out into the unknown darkness of Shanghai.

As I entered, for a split second it was as if time had stretched through space and a tiny portal had opened up in which I could hear a harmonic whisper resonating: xie xie, xie xie, xie xie. It was so persistent I had to stop in my tracks and listen. And as I listened I was overcome with gratitude for that moment and for that sound and for the travel that had brought these words and a music so delicate and quiet I had to stop and breathe deeply if I wanted to hear it whisper xie xie, share share, share share – thank you, thank you – as the scent of jasmine from near and far slowly filled the room.

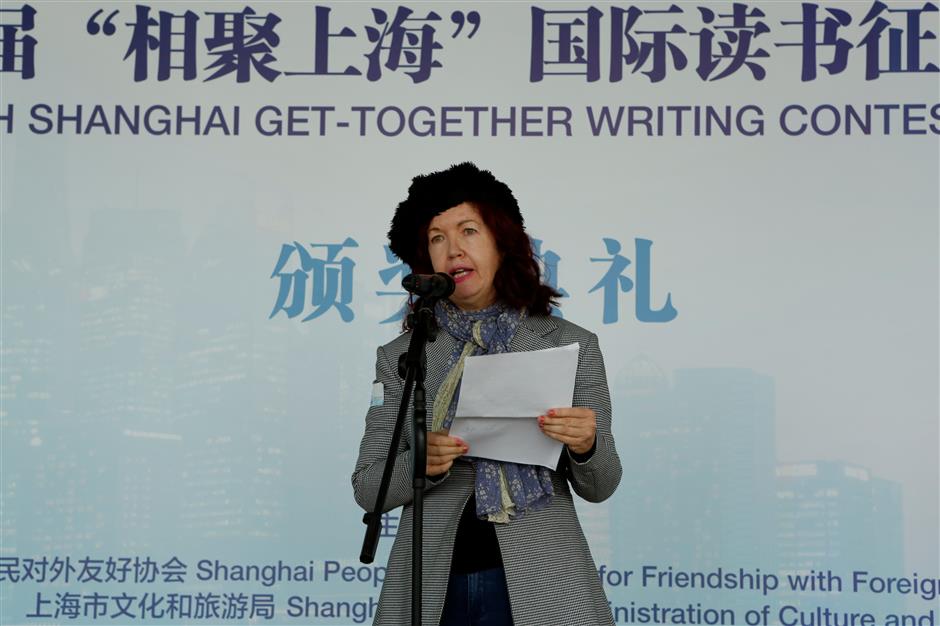

Linda Neil delivers a speech during the awarding ceremony of the 5th Shanghai Get-together Writing Contest.

A Pilgrimage to Zhongshan Park

The author flew to Shanghai for the award ceremony of the writing contest. She returned to Zhongshan Park in search of the character from her first story ...

The cab ride to Zhongshan Park took longer than I expected. We stopped and started so many times in the gridlocked traffic that both the taxi driver and I began to throw up our hands and laugh in unison.

When he finally dropped me outside the Renaissance Hotel, I couldn’t get my bearings. I knew I had to find the Starbucks near the station on Huichan Road, but I was disorientated and headed in the opposite direction before I found myself in the Galaxy Mall walking back through crowds of Saturday shoppers snapping up pre-Christmas bargains. Had Zhongshan Park changed that much? Or was my memory of the place after seven years unreliable?

I finally found another Starbucks where staff pointed me in the right direction and, suddenly, there I was crossing the road to Zhongshan Park station, scanning the crowds for a tiny lady with a big smile on a bike festooned with flowers. I couldn’t see anyone familiar, but I headed towards the Starbucks sign and the area outside the café where she used to sell her blooms.

I did not expect to find the woman whom I called The Flower Lady of Zhongshan Park, which is the name of the story I wrote about her and which has brought me back to this city that I love all these years later. I guess you might say, though, that I was making a kind of pilgrimage — which might magically produce a miracle — back to the place where I once bought jasmine from her because it reminded me of home. I had heard that a lot of street vendors has been moved on, that the police had cracked down on their brand of itinerant commerce. I knew her life would have always been precarious but perhaps, I thought, perhaps she might have made it through the tough times and maintained her spot.

When I finally got to the area where we used to laugh together, the only people there were a uniformed guard and a young woman in colourful clothes holding an advertising placard. On the ground at her feet, the broken skin of a pink balloon and some glitter.

She smiled at me and waved the sign. I gathered from the visuals that there was a mobile phone sale on at the tech shop inside the building. I shook my head, laughed. She nodded hers, laughed too. I pointed down at the shattered balloon at her feet, raised my eyebrows. What happened? She jabbed the air above her head. Poof!

We both laughed again, the same way the flower lady and I used to laugh when we tried to communicate using the international language of mime and sound effects. I missed her. But here was the balloon lady — or should I say the tech lady — standing in her spot waving goodbye, as my other lady used to, as I headed into Starbucks.

On the ride home a single leaf blew in through the window of the taxi and came to rest in my lap. It was brown and curling at the edges, reminding me that it was autumn in Shanghai. I thought of the flower lady, somewhere in China — I didn’t know where — riding her bike decorated with autumn flowers along a boulevard of shedding sycamore trees. I looked out the window as we headed back to the hotel and whispered to her in gratitude, for her memory which had brought me here, and for this new memory that I would carry back home: Xie xie. Xie xie. Thank you. Thank you.