Family finances record a fascinating past

(From left) Chen Huili, Chen Huishan, Chen Huimei and Chen Huiduo browse through their father Chen Qingyang's account books in Chen Huimei's home in Shanghai in June 2019.

Details of an ordinary family’s daily expenses may seem trivial and insignificant but over 70 years of meticulous bookkeeping offer an intriguing window into not only a particular household but into our shared past.

Shanghai native Chen Qingyang wrote down everything the family earned and spent, from food, clothing and transport to exchanges of personal favors, between 1947 and 2017. The 29 account books were donated by his children and are now in the Shanghai History Museum as a valuable chronicle of economic and social development.

Chen, who was born in 1924, graduated from the former Nieh Chih Kuei Public School for Chinese and the Shanghai University of Finance and Economics. As one of the first 100 certified public accountants after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, he worked for the Shanghai shipping administration and a shipyard company in the city. After he retired in 1979, he established the Jiangnan accounting firm, working as a partner until the age of 80.

A wedding photo of Chen Qingyang and his then fiancee Wang Jingxun in 1947

Chen Qingyang (in red circle) poses for a group photo of a brass band of the East China Maritime Shipping Administration in 1951.

The account books mention four currencies: fabi, or legal tender (before July 1948); gold yuan note (August 1948-June 1949); the first series of renminbi, or the yuan (December 1948-1955); and the current yuan (March 1955 to today).

They record the hyperinflation before liberation. For example, when his eldest daughter Chen Huimei was born in April 1949, the hospital charges for the mother were 14.5 million gold yuan notes, and two teats cost 400,000.

The price of eggs is another example. According to the books, in October 1947, one egg cost about 1,350 fabi; in September 1948, it cost about 185,714; in June 1949, it cost around 30 yuan; in 1956, one egg was selling for about 0.1133 yuan. In 1990, after reform and opening-up, the price of an egg rose to 0.20 yuan while in 2001, one egg cost 0.30 yuan.

That reflected China’s shift from a centrally planned economy in the 1950s to a more market-based economy introduced in the late 1970s.

Under the planned economy, the government controlled the price of land, grain, water, electricity and other daily necessities for the people and industrial and agricultural production.

Since the reform and opening-up, prices of goods and services have been determined by supply and demand.

Prices remained stable, and the monthly salary stable too, ranging from 108 yuan to 114 yuan before Chen’s retirement.

The family album taken in 1980 shows Chen Qingyang (front row, third from right), his wife Wang Jingxun (front row, third from left), their eldest child Chen Huiliang (back row, second from right), the second child Chen Huimei (front row, second from right), the third child Chen Huili (back row, third from left), the fourth child Chen Huishan (back row, right), the youngest child Chen Huiduo (front row, second from left) and some of their spouses and children.

When Chen Huili, his second daughter, was born, 2-year-old Chen Huimei was given to her mother’s good friend Mao. Chen Huimei said Mao brought her up and treated her better than her biological daughter, but she had always felt that her parents sent her to Mao’s home because they didn’t like her.

“It was not until I grew up that I knew the reason why my parents sent me to Mao’s home. It was because Mao didn’t have a regular job and she had a little child, only making a living by sewing.

“My parents wanted to help Mao but she was not willing to accept it. So my parents thought of asking her to foster me to give her some money. The account books document a sum of money of about 25 yuan per month to Mao as my living expenses. Twenty-five yuan was not a drop in the bucket back in the 1950s, almost one quarter of my father’s salary. The aid lasted for eight years,” Chen Huimei said.

In 1969, when she was barely 20 years old, shangshan xiaxiang — up to the mountains, and down to the countryside — began. The campaign launched by Chairman Mao sent educated youth — some 17 million young urban residents — to the countryside during the “cultural revolution” (1966-76) for “re-education” to “learn from farmers” and perform manual labor.

In March that year, her elder brother Chen Huiliang went to east China’s Jiangxi Province. In September, she received notice to go to northwest China’s Gansu Province. She was hesitant and her elder brother came back to Shanghai especially to persuade her.

“One’s value is not necessarily embodied in Shanghai, but in the society. Even though it’s considered to be very difficult at the beginning, as long as you go out and keep faithful to it, we shall prevail,” he said.

“After I meditated all night long, I was determined to follow the assignment. In just a few days, choking back feelings of reluctant parting from each other, my father bought all kinds of things he thought I would need and packed three big bags of luggage for me, though the country provided some allowances in kind,” Chen Huimei said.

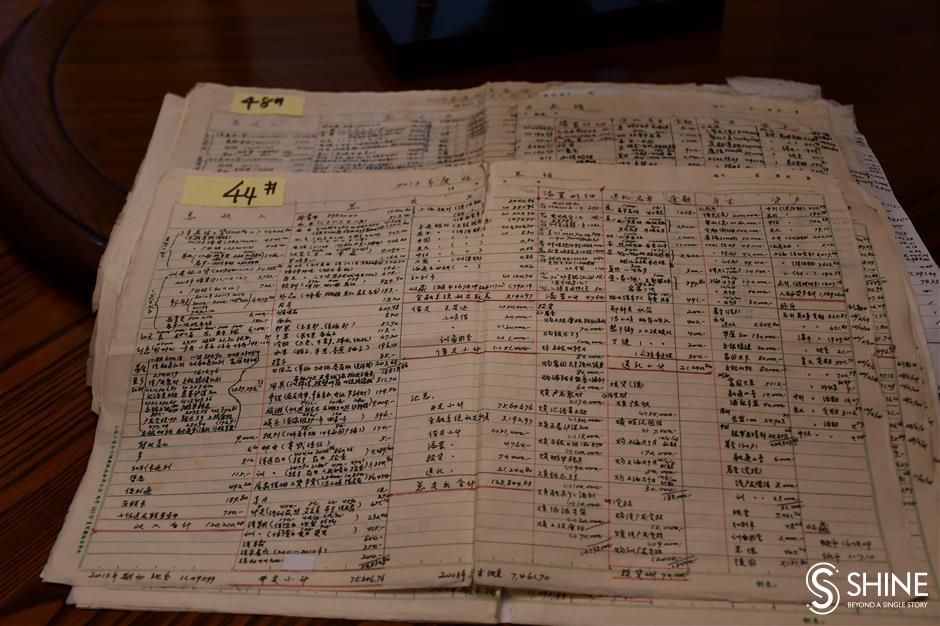

“The cramped handwriting on a big piece of paper recorded 140 items purchased for 205.28 yuan in October 1969, from small odds and ends of sewing worth only several fen (1 fen equals 0.01 yuan) to a cotton blanket worth 7.30 yuan, or an alarm clock worth 16.85 yuan, everything from food to daily necessities.”

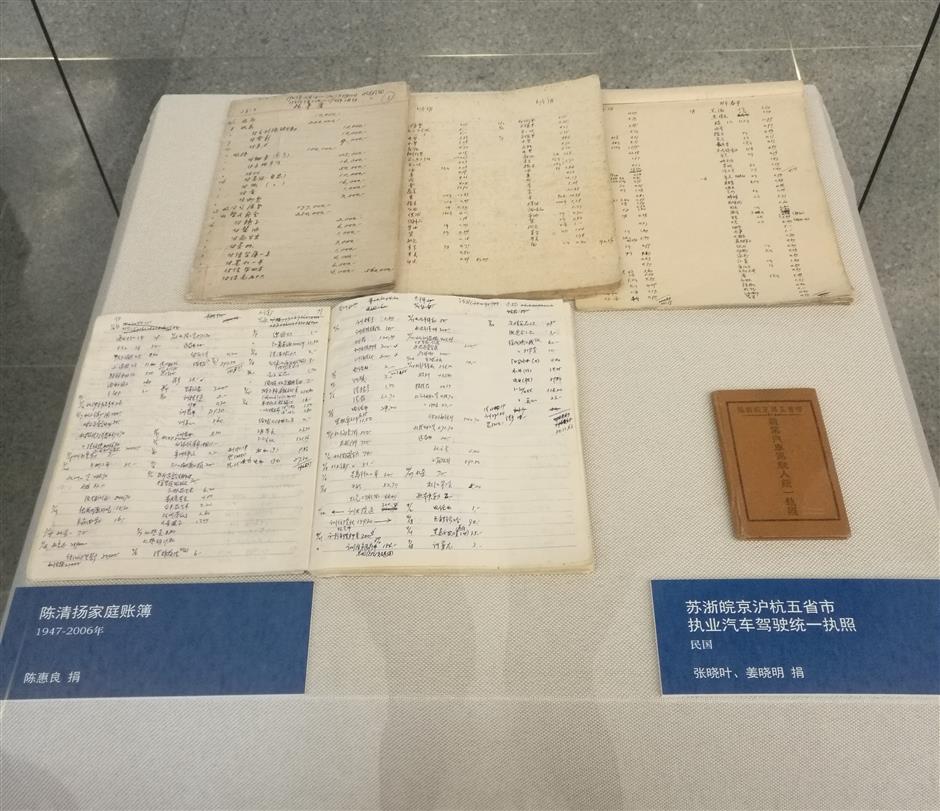

Account books kept between 1947 and 2017 by Chen Qingyang have been donated to the Shanghai History Museum.

Cramped but legible handwriting on big pieces of paper records the family's daily expenses.

At the time, the family income was almost 200 yuan a month, enough money for a family of eight (five children and Chen Qingyang’s mother) to live comfortably.

“At that time, I only knew my parents gave me an abundant supply of things, but when I saw the detailed accounts after 50 years before we donated it to the museum, I was surprised and moved at the efforts and love my parents had for me,” said Chen Huimei.

In May 1970, 16-year-old youngest brother Chen Huishan went to an army farm in northeast China’s Heilongjiang Province. “My parents responded to the call of the nation to send three children out of town in 14 months, which they considered a way of showing love for the country and the Party.

“They scrimped and saved every penny to spend on us while eating only pickles and preserved radish. For example, they would relight a used matchstick. When any colleagues or friends returned to the city, they would ask them to take goods to us. For example, the books recorded in March 1971 that the food they mailed or asked others to get to us ranged from sausages to peanut butter amounting to 65.95 yuan.”

The yearly summary for 1985 witnessed the milestones of New China’s stock trading. Shanghai Feilo Acoustic Co issued China’s first batch of shares in December 1984. In January 1985, Shanghai Yanzhong made the first public offering of standardized corporate equity. With his financial savvy, Chen Qingyang bought 10 shares worth 500 yuan each of Yanzhong and another company Tianxiang.

The elderly couple poses for a picture in October 2011 in Taicang, Jiangsu Province.

Chen Qingyang (third from right), Wang Jingxun (center), Chen Huiliang (second from right), Chen Huimei (third from left), Chen Huili (second from left), Chen Huishan (right) and Chen Huiduo (left) pose for a family photo in December 2009 in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province.

His persistence in keeping accurate records of every expenditure inevitably met with strong opposition from the family.

“My mother always had quarrels with him about bookkeeping. She said: ‘It’s just accounts about daily necessaries. Why do you always bother me to recall what a few fen have been spent on? Can’t you just take it as if I had spent it on snacks?’” said Chen Huimei.

“My father said: ‘No. You must recollect it.’ My mother knew if the book could not be completed, he would not eat or sleep because he was such a conscientious person. Mother was unable to dissuade him, but had to rack her brains to remember. I had asked my father a few times: ‘Why are you so meticulous toward these account books which only involve small things? It’s not worth it!’”

Her father once told Chen Huimei: “Bookkeeping is a history which cannot be distorted and there can’t be any error. It can be turned over, passed on to next generations, so it should be accurate to the penny.

“Bookkeeping also means your life because every moment in your life goes with figures.”

She said she felt there was a strong element of truth in her father’s words in retrospect. “I had forgotten many experiences in my life, but when I saw the figures in the books, a blast from the past awakened and rediscovered forgotten memories.”

She said that one day in 2016 when her father was 92 years old and in poor physical condition, his writing was crooked and eyesight poor. “He decided to hand over the job to me and that was when I looked at the books carefully for the first time. I was amazed at my father’s conscientiousness and precision — the books from 1947 were divided by subsidiary ledgers, ledgers by categories and yearly summaries.”

When Chen Qingyang was on his deathbed, he told his children: “I have a wish. I hope my books can make contributions to our country and society. I hope they can be kept in a museum or archives and used as a reference for economic or social development research. If so, my efforts lasting 70 years are worth it.”