'Cradle of Shanghai' once a pioneer of Western & TCM medicine

Shanghai First Maternal and Child Health Hospital is nicknamed “the big cradle of Shanghai” as it receives around 30,000 babies every year. But not many people know that the creamy-hued building on 536 Changle Road opened in 1929 as “Clinique Sino-Etrangere,” an experimental hospital to include both Western and traditional Chinese medicines.

“The Clinique Sino-Etrangere, or Sino-Foreign Clinic, opened on Rue Bourgeat (today’s Changle Road) with Dr P. Lambert as the hospital’s Western doctor and Lu Zhong’an as its TCM doctor. The clinic’s treatments, combining Western and Chinese medicines, were effective and popular among its patients. It was often fully occupied,” said Lu Ming, an expert of Shanghai Medical History from Shanghai No. 4 People’s Hospital.

The creamy-hued building on 536 Changle Road opened in 1929 as the Sino-Foreign Clinic to include both Western and traditional Chinese medicines.

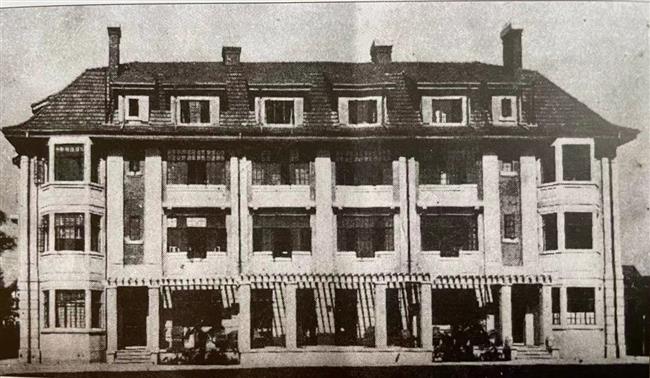

A file photo shows the clinic is a classical architecture in a light color with possibly red roof tiles.

On July 14, 1934, the building was published, among a rainbow of 60 stylish buildings designed by Leonard Veysseyre & Kruze, along with the firm’s group photo and a map of the former French concession. The prolific French architectural firm took out a full-page advertisement in Le Journal De Shanghai.

Leonard, Veysseyre & Kruze is an unfamiliar name to many today but the firm’s architectural works, included the white, classic Okura Garden Hotel and the grand, chocolate-hued Bearn Apartments on Huaihai Road, are familiar to many in Shanghai.

The firm was co-founded by two talented French architects, Alexandre Leonard and Paul Veysseyre in Shanghai in the 1920s. When designing the Sino-Foreign clinic in 1926, they had just completed the new Cercle Sportif Francais (today’s Okura Garden Hotel) in 1925 which brought huge success. The third partner, Arthur Kruze, joined them in 1934.

According to a new edition of “The Evolution of Shanghai Architecture In Modern Times” by Tongji University professor Zheng Shiling, it was estimated that more than 60 buildings designed by the French firm still exist in Shanghai, including two ward buildings in today’s Ruijin Hospital that were previously introduced in this hospital series.

“Leonard, Veysseyre & Kruze was the most important French architectural firm in modern Shanghai, which made a great contribution to the architectural design of modern architecture and tall apartment buildings. Their works showcasing a flavor of French culture had largely influenced the forming of urban spaces in the former Shanghai French Concession,” Professor Zheng wrote in his book.

A full-page advert of the French firm on Le Journal De Shanghai in 1934

Tongji University researcher Chen Feng revealed in his Masters thesis on the French firm that Alexandre Leonard had studied in the famous L’Ecole des Beau-Arts de Paris and Paul Veysseyre had learned from the maestro G. Chedanne. Both of them joined the fight against Germany in World War I, got injured and received several awards. They met in Shanghai in 1922 and founded the architectural firm.

“Their work achieved great success by demonstrating a new style and perfectly realizing it in architecture. Largely owing to their work, the former French concession had been keeping up with world’s architectural trend,” scholar Chen said.

Chen classifies their works into four periods: garden residences from 1922 to 1924; Western classic architecture from 1925 to 1928; Art Deco buildings from 1929 to 1932 and modern works from 1933 to 1936. The creamy-hued clinic building was one of the Western classic buildings designed in 1926.

Compared with the firm’s more famous works like Cercle Sportif Francais, there was little architectural record of this quiet clinic. Black-and-white historical photos show it’s a classical architecture in a light color with, possibly, red roof tiles. The facade is graced by Mansard windows, protruding windows and verandas.

The facade is graced by protruding windows.

It’s interesting that most founders of the Sino-Foreign Clinic had French connections.

According to Zheng Wei’s master thesis on the Sino-Foreign Clinic, the institution was proposed to be founded by Shijie She or the World Society, which was founded by Chinese intellectuals in Paris in the 1910s to promote revolution, science and new culture. The society was famous for its “Work-Study Movement” that sent many young Chinese to study in France starting in 1919. The movement later provided China a considerable number of open-minded talents, including Chinese leaders Zhou Enlai, Deng Xiaoping and Chen Yi. The society’s library and school were located at 393 Wukang Road, where British author/playwright George Bernard Shaw visited in 1933.

It was socialist/educator Li Shizeng, the main founder of the World Society, diplomat Chu Minyi and French doctor Jean Bussiere, among others, who established the East-meet-West clinic. The purpose was to make an experiment to permeate Chinese and Western medicines.

“The clinic was the first one to house divisions of both Western and traditional Chinese medicines. The division of Western medicine threw its doors open in April 1929 while its TCM division opened in July of the same year. The opening speech noted that it was the first clinic to start the mutual help of the two medicines,” Zheng Wei, a researcher from Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine wrote in the thesis named “Study on Sino-Foreign Clinic in Modern Times.”

The clinic was not only experimental, but also featured a nice environment and advanced equipment.

“The environment is quiet, the air is fresh and the clinic is elegant and magnificent, with comfortably decorated wards and excellent facilities. It’s very suitable for recuperation. The equipment is advanced, with rooms for solar treatment and X-ray machines,” reported Chinese newspaper Shen Pao on December 17, 1929

In addition, the clinic employed only famous foreign and Chinese experts. Lu Zhong’an (1882-1949), head of its TCM division, was famous for his superb skills using Chinese herb “Huangqi” or Astragalus mongholicus for treating hard diseases. Nicknamed “Lu Huangqi,” he was popular among Chinese elites and had cured the diabetes of renowned scholar Hu Shi and Kuomintang senior leader Zhang Jingjiang. He also treated Dr Sun Yat-sen during his final days. On July 17, 1929 the clinic invited Swiss surgeon P. Calame, former head of the Ophthalmic Hospital of the Lausanne University to see outpatients.

During World War II, the clinic became one of the hospitals in the city to treat wounded Chinese soldiers.

The funding of the clinic mainly came from the Boxer indemnity, hospital profits and social funds. The clinic treated both “charitable” and “non-charitable” patients. The “non-charitable” part is the main source of operating income for the medical institution.

According to French doctor P. Lambert’s speech on a medical gathering on June 27, 1929, the clinic offered the most up-to-date facilities and its considerate nursing service made patients feel at home. Patients could also invite doctors from other hospitals to come over for medical help. So the fees for these “non-charitable” patients were expensive. However the hospital also gave free treatment and medicines to poor patients and contributed to public health work.

Zheng adds that the clinic was operated in a scientific, flexible way to add medical services when needed. On December 28, 1934, the clinic published a notice in the “Shen Pao” newspaper that it would open an outpatient department for obstetrics and pediatrics to answer growing demands.

In August 1947, the clinic added a department of gastroenterology with a new X-ray machine, gastroscope and rectal scope as there were more patients in the city suffering from digestive problems.

“The clinic was founded with a trend of thoughts and exploration to ‘make traditional Chinese medicine more scientific.’ The clinic had hired a galaxy of famous foreign and Chinese, Western and TCM doctors. Although in the end it did not fulfill the initial purpose to ‘permeate Western and Chinese medicines,’ it did show that the two medicines could support each other. And the clinic often made the first move. For instance, new-born babies were given the Bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccine, produced by the Shanghai Lester Institute of Medical Research in 1943, long before BCG vaccine was widely used in Shanghai,” Zheng writes in the thesis.

A group photo of the maternal hospital’s training class in 1957

A file photo of a medical worker attending a premature infant

The creamy-hued building received more new-born babies after Shanghai First Maternal and Child Health Hospital moved here in the 1950s. Today the hospital delivers around 30,000 babies every year in both its Western branch on Changle Road and its Eastern branch in the Pudong New Area. Among every five or six new-born babies in Shanghai, one is born in this hospital. The creamy-hued building has witnessed numerous sweet family moments over the past 70 years.

Nurses prepare to receive patients on the ground floor.

On October 18, 2020, the building reopened after a restoration. Now it serves as a medical building with an outpatient department on the first floor, VIP wards on the second and top floors and an obstetrics department on the third floor. It is always full of new and expectant moms.

And it’s truly a big cradle of new-born babies and ideas.

The interior of a ward room in this historical building

Yesterday: Sino-Foreign Clinic

Today: Shanghai First Maternal and Child Health Hospital

Architect: Alexandre Leonard and Paul Veysseyre

Architectural style: Classic style

Address: 536 Changle Road

Tips: The hospital is open for patients only.