The US leads the world in science, and it also leads the world in opposition to science

Jared Diamond, a world-famous historian of societal crises and collapses who currently lives in self-imposed quarantine in California, says that when he’s not writing papers on the birds of New Guinea or playing Beethoven sonatas on the piano, he is concerned about the effect the current pandemic will have on his country and the world.

Michael Wiederstein, an executive editor at getAbstract, talked with Diamond about the public health crisis, global cooperation and the US' response to it.

Q: Mr Diamond, as of today, you are 82 years old. In this COVID-19 pandemic, you belong to the so-called “high-risk group.” How did you prepare for the current situation — where and how do you protect yourself?

A: In this situation as in every other situation in my life, I practice the attitude of constructive paranoia that I’ve learned from my lifetime of working in New Guinea. That is, I think of everything that could possibly go wrong, I prepare for it, and then I go on to enjoy life. In the current situation I am staying in my house except to take a bird-watching walk each morning.

Q: What does human history tell us about the right and wrong way to deal with pandemics?

A: The last few months have told us a lot about the right way and the wrong way! For example, here in the United States, health policy is largely determined by our 50 states rather than by our federal government.

Our 50 state governors differ greatly: Some of them make a practice of doing things the wrong way, and others do things the right way. The governor of my state of California, Governor Newsom, has been careful: He imposed the first state lockdown in the United States, and as a result the case buildup in California has been much slower than in other populous states.

Q: In “Upheaval — Turning Points for Nations in Crisis,” you devoted much of your analysis to the United States today. In the US, it seems like history is repeating itself in the way officials dealt with the 1918 influenza pandemic. While many politicians — arguing with the state of science — restricted personal freedoms to prevent a catastrophic spread, others just advise to pray. The outcome differs dramatically.

A: Indeed, one of the most puzzling features of the US, difficult for non-Americans as well as for many Americans themselves to understand, is why the country with the most advanced science and technology in the world is also the first-world country with the most opposition or indifference to science.

Q: You wrote that “denial” was and is one of American society’s biggest problems, that there was and is no consensus at all that the country was already in a threatening crisis before the pandemic. You demonstrated that social inequality is an additional and significant risk for American society and that violent unrest is, therefore, very likely in the foreseeable future.

A: That’s right. Political and social polarization, and resulting unrest, are major problems in the US today — perhaps the most fundamental problem.

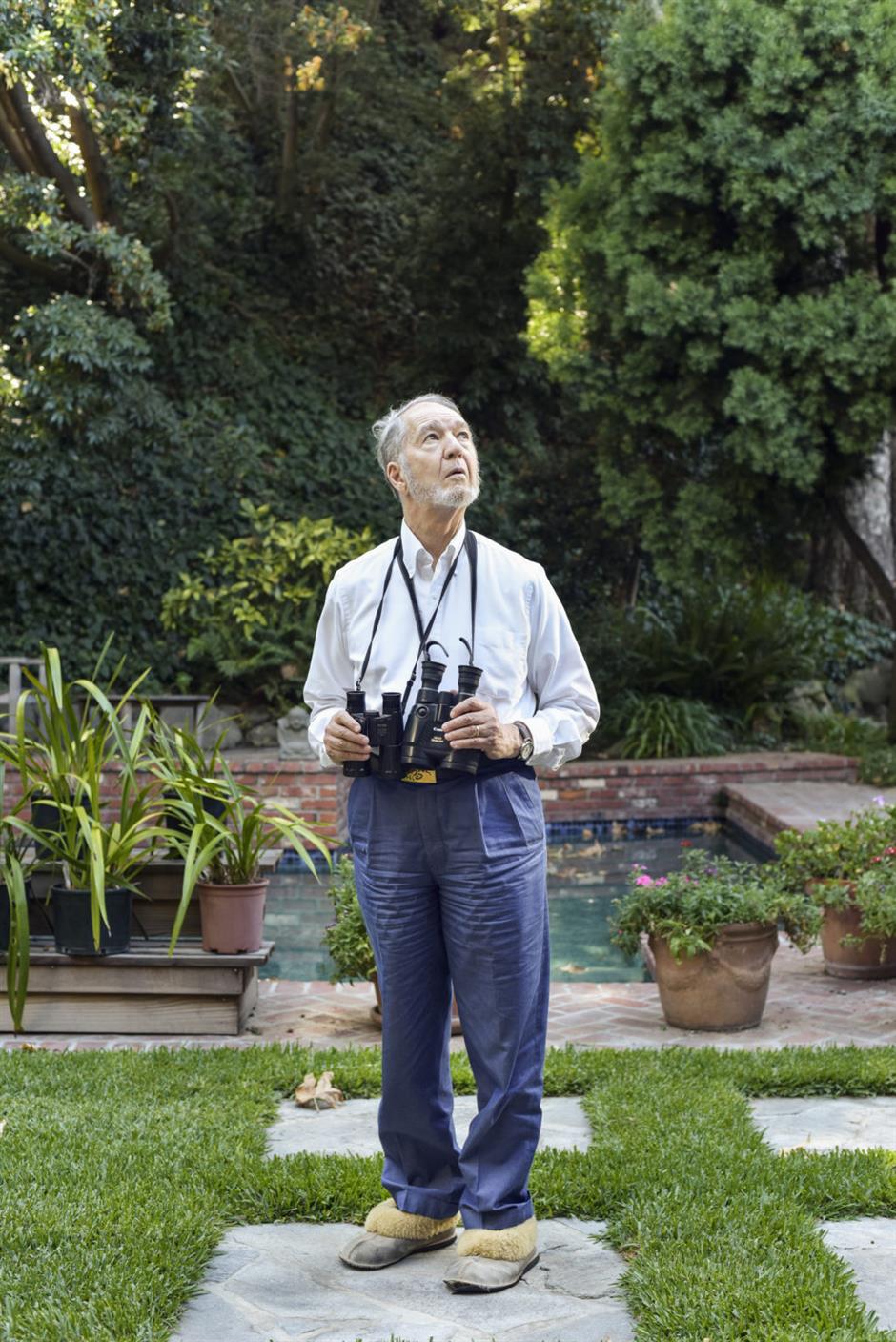

Jared Diamond is bird watching in his backyard at home in the Bel-Air neighborhood of Los Angeles.

Q: So, will the current pandemic lead to a renewed convergence of culture — or accelerate its disintegration?

A: Will this lead to a search for unity, or instead to further disintegration? Come back in two years and ask me that question again!

If the president of the United States were a courageous leader as are the governors of California, New York, Montana and some other states, such a president could lead our country and call on all Americans to focus on what we share in common, and to join in combating the current enemy of the epidemic.

Q: Yet, the biggest problem of American society, as you wrote, is the refusal to learn from others. Instead of taking responsibility and honestly assessing oneself, one seeks blame on others.

A: Years from now in the future, readers of my recent book may think that I wrote the book after the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis.

Q: Let’s briefly go through the steps of crisis management you identified in “Upheaval.” What do they actually mean in the face of the current crisis?

A: The COVID-19 crisis illustrates well that list of a dozen outcome predictors.

The first step in dealing with either a personal crisis or a national crisis, familiar to all of us who have gone through a personal crisis — which means every one of us — is to acknowledge that oneself or one’s country is in a crisis.

The second step, also familiar to all of us from personal experience, is to accept responsibility that one has to do something about the crisis oneself, and that blaming others or indulging in self-pity gets one nowhere.

Again, COVID-19 illustrates both good and bad examples: My own president provides a bad example, in focusing on blaming China, while other countries like Vietnam and New Zealand focused on doing something about the crisis rather than assigning blame elsewhere.

Q: This step is of great importance for the third, decisive one, right?

A: Yes. It’s crisis resolution, again familiar to all of us from personal experience: Look for models of how other people have solved, or have refused to solve, a similar problem. Nations also learn from models, or refuse to learn from models ... Already in January, before there had been any case of COVID-19 in Vietnam, the Vietnamese government remembered 2003 and imposed lockdown and tracking. This crisis perspective of my book leaves me cautiously optimistic about the outcome of our current global COVID-19 crisis.

Q: All this sounds like we reached a “tipping point” that is likely to change the future of our societies.

A: The unique feature of the COVID-19 crisis in history is that it is the first world crisis that the world acknowledges as a shared crisis. Of course, the world faces other crises, notably climate change and resource depletion and inequality. But climate change doesn’t kill people within two days, and the deaths of people who die of respiratory diseases and food shortages and other long-term consequences of climate change don’t say to themselves, “I’m dying of climate change!” They instead say that they are dying of a respiratory disease or of starvation. But COVID-19 kills quickly, and if you are dying of COVID-19, there is no doubt that you are dying of COVID-19.

Hence the world is being forced to acknowledge that COVID-19 is a world crisis, one that affects every country, and no country can solve it by itself.

Even if Germany stamps out COVID-19 completely within its own borders, but if the virus survives in Moldova or Libya or any other country, it will be only a matter of time before Germany gets reinfected.

Q: So, what makes you optimistic for the rest of the year — and the following?

A: It will at first seem ironic, cruelly ironic, to say that a pandemic that will kill millions of people provides any cause for optimism. But I predict that it will give us cause for optimism.

I hope that, just as COVID-19 will motivate the world to adopt a global approach to this world problem, it will also serve as a model by motivating the world to adopt a global approach to solving the world crises of climate change and resource depletion and inequality.

If that prediction of mine proves true, then the COVID-19 crisis will have a silver lining: For the first time in world history, a global pandemic will have created a model of shared motivation among the world’s people to solve a world problem.

(Visit journal.getabstract.com for the original interview.)