Shanghai's latest export to the UK: math

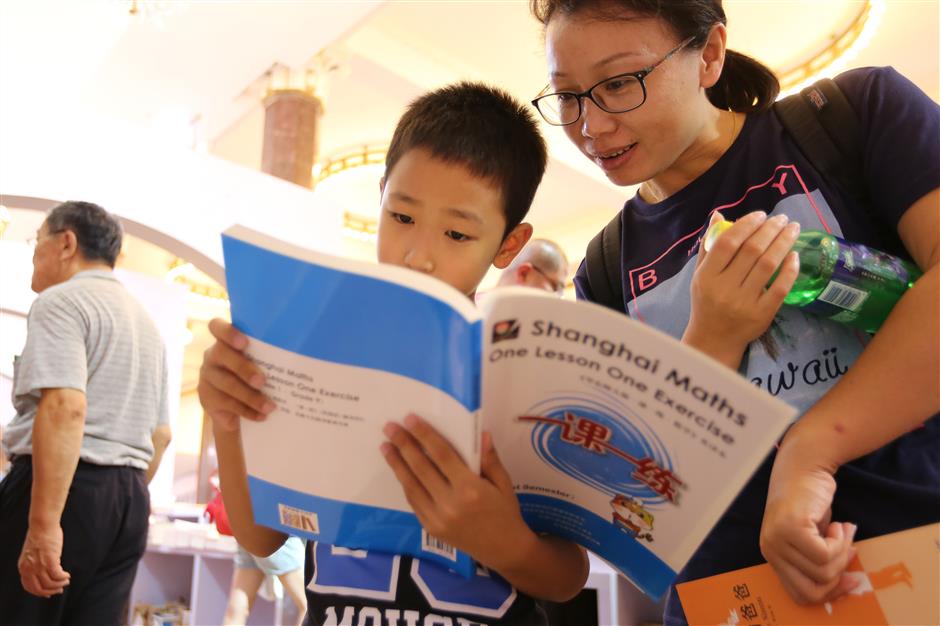

A boy reads attentively the English version of "One Lesson One Exercise" at Shanghai Book Fair.

The English version of a popular set of Shanghai math books which debuted at the recent Shanghai Book Fair attracted a great number of interested Chinese readers.

Chinese publishers and scholars have been inspired by the introduction of Shanghai math books to the United Kingdom and are bringing the fruit of such exchanges back to the city.

In Britain, pupils may need to sharpen their pencils in preparation to do math “the Shanghai way.”

In March, HarperCollins, one of the world’s largest publishing companies, signed an agreement with Shanghai Century Publishing Group at the London Book Fair to publish an English version of the math textbooks used in Shanghai’s primary schools.

The series of 36 books called “Real Shanghai Mathematics” will be used by British students from September as the new term begins.

Chinese students perform excellently in math in the Program for International Student Assessment, a worldwide study assessing 15-year-olds on key knowledge and skills, mainly in the areas of reading, math and science.

According to PISA website statistics, students from Shanghai came first in 2012 in PISA, which has been held every three years since 2000. British youngsters were 25 places behind. In 2015, Chinese students also performed significantly better than their British counterparts.

In 2016, the UK Department for Education announced that it would spend 41 million pounds (US$53 million) on a four-year program to spread the Shanghai Teaching for Mastery Program in the country.

Chen Yilin, a math teacher from Shanghai Luwan No. 1 Primary School, helped translate “Real Shanghai Mathematics” into English.

“The team spent three months on translation, word-for-word, with some adaptations in accordance with the requirements of the British side,” she says.

The deal between HarperCollins and Shanghai Century Publishing Group is the first time that a whole series of Chinese textbooks has been adopted by the national education system of a developed economy.

But it is not the first time HarperCollins has taken Chinese textbooks overseas.

In 2015, the company published an English version of “The Shanghai Math Project,” supplementary study materials originally published by East China Normal University Press and used by Shanghai students for more than 20 years.

“The Shanghai Math Project” has not just been translated, but has been adapted to British needs.

“Given the cultural and curricular differences, merely translating a Shanghai textbook into English would cause problems for students, so the adaption work is important,” says Ni Ming of East China Normal University Press.

“Still, we have delivered the essence of Shanghai math to British teachers and students.”

More than 400 schools in Britain are already using “The Shanghai Math Project.”

The feedback is mostly positive,” says Fan Lianghuo of the University of Southampton.

“The Shanghai Math Project” and “Real Shanghai Mathematics” are just the beginning, Fan says.

The English version of "Shanghai Maths" is very popular and well received at the recent book fair.

No child left behind

Academic exchanges between math teachers from China and Britain started in 2014.

Teacher Chen spent two weeks teaching in Thorndown Primary School in Cambridgeshire in January last year.

“Most British classes are divided into groups based on ability, with each group being taught at varying levels,” Chen says. “The Shanghai mastery approach requires every student to completely master a concept before the teacher moves on to the next.”

In Chen’s class in Thorndown, she taught the same way she did in Shanghai, which encourages whole-class interaction to make sure no one lags behind. She also demonstrated the teacher-led mastery method to groups of British teachers.

“There used to be a perception among many British teachers that teacher-led lessons were boring,” Chen says. “After my class, I was told by British teachers that they found my method more effective. Teachers’ talks can be interactive. Students learn through questioning and demonstration rather than figuring out the answer all by themselves.”

British Schools Minister Nick Gibb has said in a speech last year there was much to learn from the Chinese approach to teaching mathematics.

Shanghai teaching methods depend upon whole class instruction from the teacher, with constant questioning and interaction between the teacher and the class, Gibb says.

Two-way communication

Imraan Ahmed’s 11-year-old daughter studies at a private school in Birmingham, and takes her math score very seriously.

“If you want a better future or career, you’d better learn math quickly and hard, especially given Brexit,” says the owner of a fashion store in Britain’s second largest city.

“It’s not only about math, but also about competitiveness,” he says.

According to a survey in British newspaper The Telegraph in 2015, over three quarters of employers in Britain believed that action was needed to improve math, following concerns that innumeracy could have a real impact on business.

Now, while the British government is pursuing new ideas from China, the communication in education between China and Britain is not one-way.

“Education is a long-term process. We should learn from each other to improve,” Chen says.

“Things can be learned from British schools such as the richness of their extracurricular activities, the well-designed teaching aids and a joyful learning environment in classrooms,” she says.