History's footprint in a site that welcomed Jewish war refugees

It was a rainy evening when I visited the Hebin Building alongside Suzhou Creek. The roadway was almost empty under dim streetlights, and a chilly wind swirled wet steam from the waters.

The S-shaped building resembled an enormous shadow against the night sky as I looked up at it. Light glistened behind countless windows.

My destination was Unit 526. Yes, one of the largest residential buildings in Shanghai has more than 30 suites spread across 11 floors. Originally it had eight stories.

Adam Lin, the man with whom I had an appointment, is an editor in the local financial media. He rented Unit 526 and restored it to the style of the 1930s and 40s, with the help of friends and the consent of the apartment owner.

“I studied the history of the Jews and earned a master’s degree in the United States,” Lin told me. “I was always interested in this building because it was formerly owned by a Jewish group and was the first stop for many Jewish refugees fleeing to Shanghai from the Nazis in World War II.”

His historical facts are correct. The original owner of the building, E.D. Sassoon & Co, is mostly remembered for its construction of the Peace Hotel, now known as the Fairmont Peace Hotel, on the Bund. The Hebin Building was finished in 1935.

Lin and his friends wanted to create a more open space in the apartment to provide room for visitors interested in the history of the building or events in the city during that era. Small salons and exhibitions were also envisioned.

Lin was late to our meeting, so I wandered around the building by myself for a while. It stretches an entire block, with multiple entrances and address numbers. One of them, “400 North Suzhou Road,” led to the main lobby, which swept me back a half century.

The mosaic floor, a concierge room and rows of green letter boxes on the wall are no longer popular in newly built residential complexes. Maybe because of its unique appearance, the building often serves as a backdrop for TV dramas.

After I reached the fifth floor on a narrow elevator, a long and winding corridor spread in front of me. To be honest, walking in the quiet, empty corridor at night raised a few goosebumps.

The passageway was lit by only cold light from above. Windows and exits were scattered in dark corners, giving the impression that something might jump out from the shadows.

The long, dim corridor of the building often appears in local TV drama shows.

I thought this 85-year-old building that welcomed hundreds of thousands of refugees must have many tales to tell — the good, the bad, the normal and the bizarre.

I reached Unit 526 not long before Lin arrived, panting, with flushed cheeks and hair wet.

“Sorry for being late,” he said and unlocked the door.

I wasn’t quite prepared for my initial impression. The apartment had a structure alien to me. There was a hallway connecting several rooms, two bedrooms, two storerooms and a bathroom.

Lin said one of the bedrooms is occupied by another renter. He told me his renovation covered the main living room and master bedroom, the balcony and the bathroom.

I was invited into the living room and sat on a vintage sofa covered in crimson fabric. The 1930s French-style sofa complemented the Chinoiserie style of the entire room. Chinoiserie was once popular in Europe, inspired by the art and designs of 18th century Asia.

“A friend of mine designed the room and found most of the vintage furniture you see here,” Lin explained. “Our research showed that Chinoiserie was a style favored by many foreign people living in Shanghai back then.”

A folding screen separates a queen-size bed from the living area. The black lacquer screen was painted with mountains, peacocks and wintersweet blooms — very common elements in traditional Chinese art. But its style is a mixture of Chinese, Western and Japanese paintings. Apparently, it’s a typical Chinoiserie piece. A cabinet opposite the sofa has the same features.

“These two pieces of furniture were made during a period of ‘foreign-exchange earnings’ after the establishment of the People’s Republic,” Lin said. “At that time, the country produced many things, such as furniture and porcelain, especially for export, so the designs were tailored to Western tastes.”

The Chinoiserie-style folding screen was made, particularly for export, after the establishment of the People’s Republic in 1949.

An old door and shelving in the bathroom of the unit were retained.

To pick the most suitable furniture and fulfill his curiosity about the building, Lin did research on residents living in the building in the 1930s and 40s.

He found old phone directory Yellow Pages in English that recorded the names of the residents. Among those residents were a Mr and Mrs Grainger, probably from the United Kingdom. Later, an Ed Paine from the US, who worked for the United Nations, resided there for several years. Lin managed to find photos of the letters Paine sent home to Sacramento, California.

The Yellow Pages showed that most residents were expats — white-collar workers at companies on and around the Bund. They were not as wealthy as the foreign business tycoons who once flourished in the city, but they enjoyed a comfortable life. Many showed interest in Oriental culture and arts.

“The building had very complete heating system,” Lin told me. “The west wing was earmarked for household maids, with separate stairways and elevators. In the maids’ quarters, electric bells were installed so that residents could call their servants. As you can imagine, most of the maids were Chinese.”

Residents chartered their own rickshaws, he said. Every morning lines of rickshaws would appear in front of the building to take people to their workplaces.

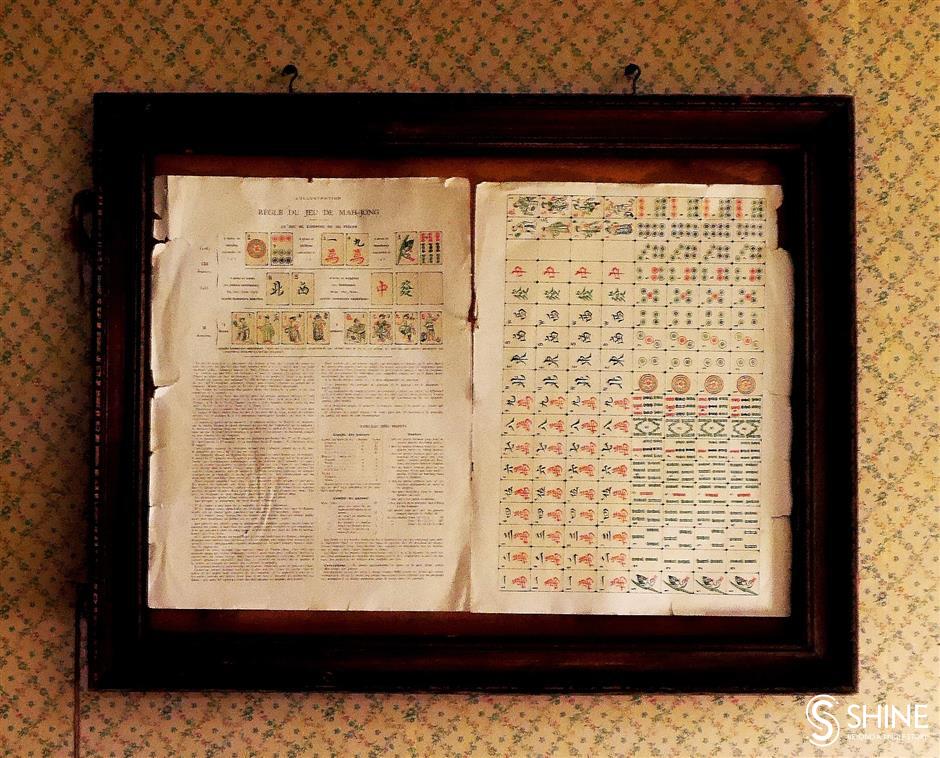

Pages from an old French magazine about mahjong playing are a decorative picture on a wall.

Lin said he felt a connection with the building even before he rented the suite. When he first came to Shanghai, he often passed by it and became familiar with the surroundings. When looking for a place to live, he happened to meet the current owner of Unit 526. The two hit it off immediately.

“Different eras left their respective marks in rooms, and when we decided to renovate, we tried to keep them to the extent possible,” he said. “The wallpaper around the windows was a vestige of residents during the late 1980s and early 90s, and the two chairs belong to the current owner, my landlord.”

The building has endless stories, and Lin keeps collecting them. He has talked with many older residents who have lived in the building for decades, listening to their personal tales and the anecdotes they heard secondhand.

Alas, my visit had come to an end. Lin walked me out. The corridor seemed somehow brighter than when I arrived. Several people were waiting for the elevator. Some of them were foreigners.

“Today, some expats choose to live here because they are fascinated by the décor or the history of the building,” Lin said.

When I walked out of the elevator on ground floor, the lobby was crowded with people. A rocker-arm camera had been set up at the front gate, and security-looking men murmured about “fans sneaking onto the set.” Apparently, another TV shoot was about to happen.

The Hebin Building is as well-loved today as it was 85 years ago.

If you go:

A WeChat official account entitled “Living Room of Hebin Building” (河滨客厅) has been put online, giving viewers access to future events and exhibitions in Unit 526.