Podcast: Chinese evangelist for the power of art therapy

Podcast EP18

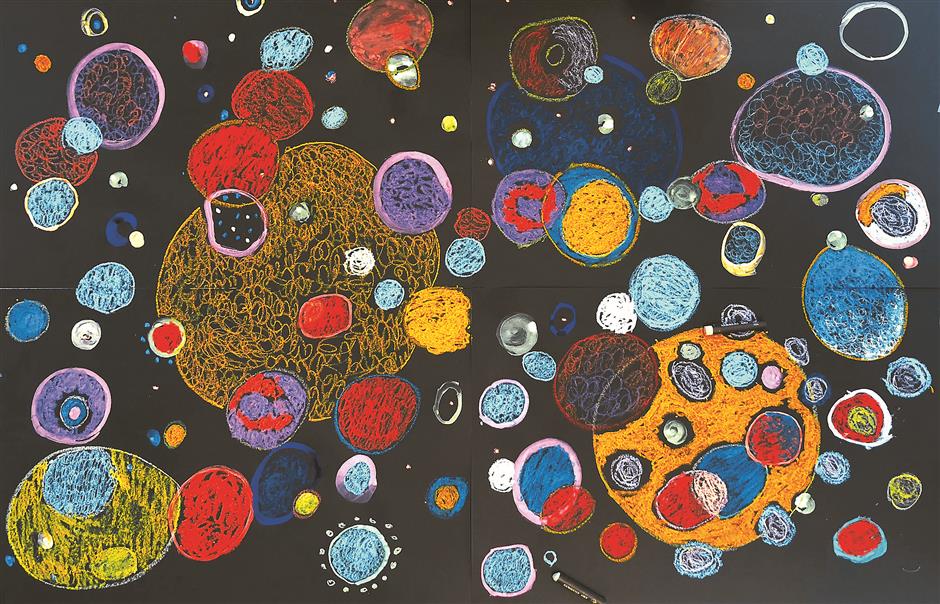

A piece of artwork by clients of Shi Yunyuan. Graduated from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago with a master's degree in art therapy and counselling, Shi is now teaching art therapy at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing.

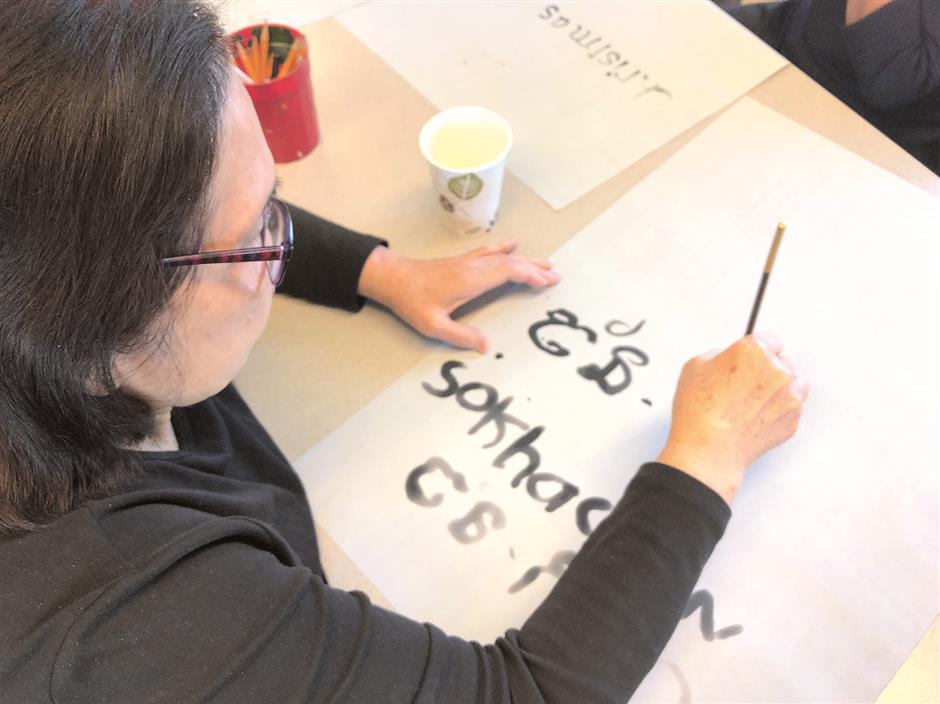

Learning calligraphy at an early age, Shi Yunyuan firmly believes in the power of art.

"It is because of my trust in art that I choose to study art therapy abroad," Shi said. "I've been getting along with art for quite a long time, and the experience and its power are beyond words."

Graduated from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago with a master's degree in art therapy and counselling, Shi is now teaching and leading the disciplinary development of art therapy at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing.

"I was thrilled when I learned about the art therapy major. I like the idea that art heals," she said. "Art can definitely make us feel good, but how can it heal effectively? I grew so interested in it, and I felt that's the thing I want to do in the future."

This week, we still have Shi with us, and she'll be sharing her understanding of art therapy, the "unanswered questions" and the challenges of its localization in China.

Shi Yunyuan

Q: How do you understand art therapy now after studying it for three years in Chicago?

A: Basically, it's hard to explain what art therapy is in one sentence. As we mentioned before, it's an interdisciplinary subject.

Meanwhile, it is also a clearly labelled subject. It is a new type of productivity that lies in the overlapping area of art, health management and mental health institutions, and social public service centers. This productivity can be related to economics, culture and even new types of art and technology.

Surely the term "art therapy" can be misread. When people here the word "therapy," many believe it is to treat a certain disease, or it can only be applied to sick people. To some extent, the translation from English to Chinese results in misunderstanding. Even in today's academic world, ideas vary as to what the exact words for art therapy should be in Chinese.

However, I don't think there's any need to be obsessed with finding faults in words. What concerns us is what art therapy is in nature, and what it deals with.

I believe art therapy is a kind of life philosophy with art as its core, which can inspire us with new lifestyles. I often quote a saying from "Huang Di Nei Jing" ("Medical Classic of the Yellow Emperor," the first medical book in China and the foundation of Traditional Chinese Medicine) that reads: "The best doctors prevent the disease, the average treat the pre-symptomatic cases and the lease competent treat the symptomatic cases."

There have been many effective art therapy treatments targeting various symptoms in Western countries. Compared to the West, which has an emphasis on logical thinking and deduction, we are better at understanding something in a macroscopic way.

Therefore, we can focus on how to use art as preventive measures and to call for an active lifestyle.

Art therapy sessions that Shi provided in Chicago when working as an intern at an institution for Asian refugees and immigrants.

Q: How can people have a try at art therapy, and what are the possible effects?

A: One benefit of art therapy is the power to propel social change. Art therapists are responsible for helping the public better understand what art is, and how it exists in daily life.

During the outbreak of COVID-19 in Europe, the balcony theater emerged. Just like (Joseph) Beuys once said, "Everybody is an artist."

When I worked at the center for Asian refugee and immigrants, there was a client from China who married an African-American man. She came for counselling on parent-kid relationships. Since she was a woman who grew up in China with a child raised in the West, she was greatly disturbed by how to educate and get along with her kid.

We had many art therapy-related activities to help turn her attention from caring for her kid or even controlling the kid to herself, and finding her values in life.

It was a long process. At first she completely rejected art, saying "I don't want to do art, you just tell me what to do to solve my problems." Then I discovered she's had a fondness for music ever since she was a kid, so I let her take time to find those artsy elements in life and let them play.

Everyone can have their own moments and resources with art.

Art therapy sessions that Shi provided in Chicago when working as an intern at an institution for Asian refugees and immigrants.

Q: Is it hard to make people believe in art therapy?

A: Definitely. Due to our backgrounds and the education we received, whatever we do, we want immediate feedback and results. We want to see changes right away. But art therapy does not work that way. It takes time for the public to acknowledge and accept. But I believe those who want to benefit from art and those aspiring for a better quality of life will, one day, have a go at it.

Part of Shi's artwork "66 Unanswered Questions" that reads in Chinese: "Bias and Stigmatization."

Q: You have a piece of artwork called "66 Unanswered Questions," which is your reflections on art therapy. Tell us about it.

A: It was a vital part of my graduation design. In the form of a handmade book, it is actually a cross-cultural research that clearly presents the topic and themes of my essay. It showcases the dilemma of a dual culture from my standpoint as an expat living and studying art therapy in the US. It discussed those cross-cultural problems that concern me in the development of art therapy in China. For instance, ethics, translation and occupational challenges. One of them, if my memory doesn't fail me, is how does language lead to bias and stigmatization? I hope those questions can open my mind and carry on my train of thought.

The book has no back cover but two front covers – one in Chinese and one in English. For Chinese readers, it is presented with vertical printing and Chinese calligraphy, because in the West, calligraphy represents the highest level of Chinese visual expression. And for English readers, it is printed horizontally in Roman typeface.

I hope this piece goes beyond personal expression to analyze the difficulties and challenges of practicing art therapy in China.

Part of Shi's artwork "66 Unanswered Questions"

Q: Of all those questions, which have you found answers for and which still remain unsolved?

A: I still have many of these questions on my mind, such as the one I mentioned before, "How does language lead to bias and stigmatization?" I've been thinking about it all the time – how has Chinese expression affected our acknowledgement and experience of pain, and depressed and anxious feelings?

I've been following the studies of Arthur Kleinman, an anthropologist at Harvard University, who inspired me with the psychologization of emotions. Psychology was introduced from the West. One day, we Chinese got to know the words "depression" and "anxiety" from the West. It then suddenly struck us that maybe those blue moods and nervous breakdowns are part of depression.

However, to simply label a common feeling or emotion as a certain sickness somehow affects our understanding of this mental phenomena.

Part of Shi's artwork "66 Unanswered Questions"

Q: What are the challenges of the localization of art therapy in China?

A: Today, I'd like to think of art therapy as a hybrid of Western and Eastern ways of thinking. In the West, it is very much like TCM; while in China, we consider it something very Western. In the early days of the 1960s and 70s, the practice of art therapy had already involved with Eastern ideas like meditation, mindfulness and Zen Buddhism.

On the other hand, art therapy as a non-verbal expression can play down the bias and obstacles posed by language, so that it can be experienced by all humans. When we look at master Chinese inkwash paintings and calligraphy, we feel touched. When we watch a Michael Jackson concert, we also feel touched. Even though human feelings and experience vary, there are common denominators.

I'd like to compare art therapy to a human being, who is a highly sophisticated living system full of unknowns. What we are going to do (with art therapy) is identify these unknowns and take control.

As for localization, I think of Gilles Deleuze. His secret to keeping his philosophies creative and productive was always going back to the origins. I hope we can learn from his strategy and keep going back to our forerunners and classics, and later build a connection that goes beyond simple citation and replication. In this process, we have to be very clear when developing our new ideas, when to go back and reread the classics and when to work with the forerunners and other art therapy practitioners from different cultural backgrounds with collective wisdom.

So far in China, it is still a budding field with limited scale. We'd like to do a great deal of translations and publications to provide the general public with more access to the field, and also work hard as a catalyst for social change to clear up the bias and stereotypes toward mental health problems.

There are challenges but opportunities as well.