Calling the cavalry: COVID-19 and the mental health crisis

The crisis we’re facing has affected billions of people across every nation of the world. It’s touched every community, impacted countless families and inflicted unquantifiable damage on the global economy. At present, no one can predict how this epidemic will unfold. But in 2020 alone, an estimated 450 million people are suffering.

And we’re not talking COVID-19.

Mental illness is a beast that takes many forms. Unlike the identifiable symptoms of a virus, mental health disorders are harder to spot. Despite misconception, they are complex, widespread afflictions on a continuum we're all on.

That’s not the only reason mental health disorders are hard to measure. Many suffer from multiple disorders at once. What’s more, figures rely on people speaking up about their struggle. But shame acts as a stuff gag; one shoved so far down the throat of the bound, they choke on their pain and are left suffering in silence. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports an estimated 800,000 deaths by suicide per year. That’s one every 40 seconds. Indications show that for every suicide, 20 others were attempted.

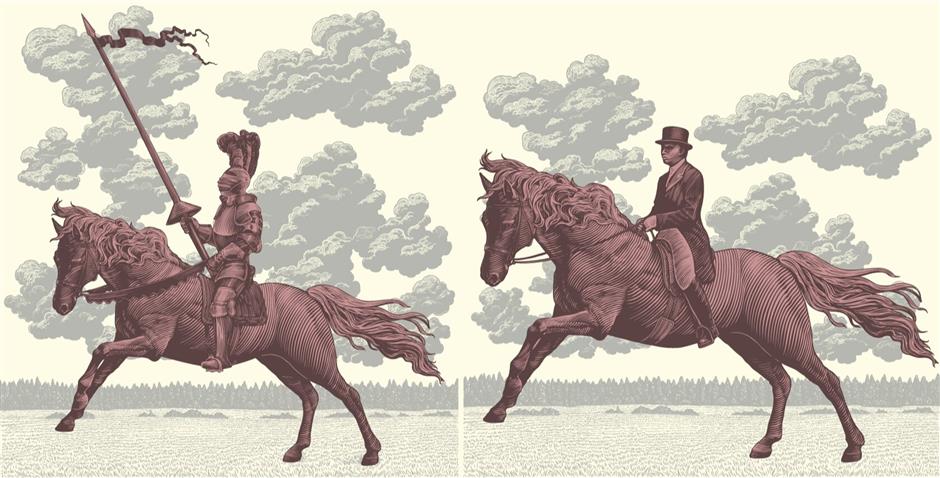

So, where’s the cavalry?

Knowing this, why haven’t nations and governments galvanized against our silent enemy? Worldwide cooperation, commitment and unprecedented spending have all been recognized as key factors in the battle against COVID-19. Winning has been the priority of every administration and privy to the front page of every newspaper.

While the WHO praises the global response to Coronavirus, it reports underinvestment in mental health care; less than US$3 per capita a year.

In China, it’s estimated some 100 million people suffer from a mental health disorder. As acknowledged by the WHO, the country has made significant efforts to overcome barriers that prevent people from accessing diagnosis and care. This includes the introduction of mental health laws that call for more facilities and better awareness. But still, it’s been suggested that China has too few specialists to meet the country’s needs, with roughly 2 registered psychiatrists per 100,000 citizens.

There’s something else to consider. As an expatriate living in China, we might think our troubles remain at home. But as international psychologist, Dr Debi Yohn puts it, “The stresses of living in a challenging new environment exacerbate these issues faster and stronger with fewer familiar resources at hand.” Approximately 174,000 expatriates are living in Shanghai. If 1 in 4 of us suffer from a mental health disorder, that equates to some 43,500 people living with a pain they can’t properly express. There’s hope. Shanghai offers several resources for expatriates with mental health concerns, everything from alcoholics anonymous to expatriate psychiatrists and psychologists.

In an interview for CNN, Dr Michael Phillips, Director of the Suicide Research and Prevention Center at Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine said, “It’s impossible to characterize the mental health of a nation, particularly on the size and diversity of China.” A study conducted by Dr Phillips with over 60,000 subjects, found rates of mental illness in China “Similar to that reported in Europe and North America.” So let’s look at that.

Amongst the richest countries in Europe, poor metal health costs the UK over £100bn a year in social and economic fallout. Yet the Mental Health Foundation reports mental health research in the UK is chronically underfunded. And while the UK government boasts a £12billion spend on mental health services in England in 2017-18, these same services are buckling at the knees. The effect? Approximately 5,821 deaths by suicide per year in England, that’s an average of 16 suicides a day. Death by suicide is now the single biggest killer of men under the age of 45 in the country.

We’ve had to systematically change our way of life to stop the spread of COVID-19. But you can’t catch a mental health disorder, right? Arguable.

Social solutions could be the key to unlocking mental health

Mental illness can be linked to three causes – biological, psychological and social; the latter two have been dangerously overlooked. The WHO cites poor mental health as a social indicator requiring social solutions. The United Nations, when referring to the treatment of depression - the most common mental health disorder – advised we shift our focus from chemical imbalances to imbalances of power. Serotonin isn’t the problem; society is.

Biology plays a part in mental illness, but when it’s not the root cause, we mustn’t make it a scapegoat for change.

Rightly, the global response to COVID-19 has been nothing short of radical. The world has responded in unison, political parties have put differences aside and governments have prioritized both time and budget to overcome the crisis.

In one of only five such addresses throughout her reign, Queen Elizabeth II gave a four-minute speech designed to rally national resolve against COVID-19.

"Together we are tackling this disease and I want to reassure you that if we remain united and resolute then we will overcome it. I hope in the years to come everyone will be able to take pride in how we responded to this challenge." – Queen Elizabeth II

In that same four minutes, 6 people will have died by suicide.

Let’s hope a similar address might one day be made by world leaders in response to the mental health crisis. That we might also take pride in our global response to the silent killer that has spread too far, for too long.

Check in with Emma Leaning is MENTAL on the first Monday of every month