'Stock Grandma' dabbles in equities to fend off boredom

Zhou Hongbao, 104, watched a TV finance channel to get news and tips on stocks.

Most elderly women concentrate on caring for grandchildren. Zhou Hongbao, 104, isn’t one of them. She is focused on price-to-earnings ratios, rates of return and moving averages. She isn’t nicknamed Stock Grandma for nothing.

Zhou keeps the television in her small living room tuned to a finance channel all day. Although she is now a bit hard of hearing, she can still rattle off the daily news of the stock market, according to the Shanghai-based Jiefang Daily.

She said investing in stocks helps fight boredom. Her 78-year-old son, surnamed Xu, assists her in her trading activities.

No doubt Zhou is probably the oldest active stock investor in Shanghai. Investment by the elderly may be rare, but it’s not unheard of. A report last year by big data institute MobTech showed that investors stretched across all age groups.

Stock trading began in Shanghai in the late 1860s and spawned its share of booms and busts over the decades. Investors won big; investors got burned. It’s not a game for the faint-hearted.

Zhou, who was born in Shanghai and now lives in Minhang District, had no interest in the stock market when she was younger. Decades later, a neighbor she has known since his boyhood told her about his grandfather, who had been active in the market.

In 1986, Shanghai Feilo Acoustics Co was the first stock in the era of the People’s Republic of China to list on what was then the over-the-counter market at Jing’an Securities Business Department. Today’s Shanghai Stock Exchange wasn’t opened until 1990.

“In the 1980s, my neighbor’s grandpa asked him to help with the stock trading,” said Zhou. “He found that one could make money investing in stocks, so he wanted to have a try on his own.”

Zhou Hongbao and her 78-year-old son discuss stock trading in her home. He relays her buy-sell orders to her brokerage firm.

One day, the neighbor appeared in Zhou’s home and asked her to pick a stock from the initial eight listed on the over-the-counter market. In a version of what might be called “dart-board investing,” she picked shares issued by Yuyuan Garden.

The neighbor subsequently invested four years of savings in the stock at a price of 11 yuan (US$1.69). The smallest parcel available for purchase was 1,000 shares.

“The price didn’t rise for a long time,” Zhou said. “But finally, it started going up. My neighbor was a patient person and didn’t sell the shares.”

Zhou began to become intrigued by stock trading but didn’t have much cash to spare at the time. Her neighbor offered to sell her 5 percent of his shares for about 500 yuan. It was a fair price, so she agreed.

When the stock price hit 30 yuan, she asked her neighbor to sell the shares. Her initial investment had almost doubled.

“Although I wasn’t clear about how it all worked, I was happy with the result,” she said.

Zhou, who was in her 70s by then, asked her son to open a stock account with a Shanghai securities firm so she could continue to dabble in shares.

In 1994, a movie called “Shanghai Fever” was released. It was about a humble bus conductor tapped by a Hong Kong trader to be his go-between in the booming Shanghai stock market. The film reinforced the widespread belief that buying stocks could make people millionaires overnight. Some who flocked to the market did indeed become wealthy; others less fortunate were wiped out.

Zhou studies stock movements every day.

Zhou always remembered her neighbor’s advice to be prudent and not get sucked into runaway bull markets.

At first, she invested 3,000 yuan on a few stocks of companies she was familiar with. She studied stock information in newspapers and from finance TV programs. She watched real-time market prices on TV.

Zhou admitted she has always been a novice trader. She can’t read technical charts, fully understand analysis by market experts or follow exactly how domestic and global events influence prices. She doesn’t know how to use a computer or a mobile phone.

According to Xu, Zhou’s buy-sell notes to him weren’t always very clear and led him sometimes to buy the wrong stocks for her.

Still, she didn’t do all that badly in her stock choices.

“If she bought 200 shares at 15 yuan each, she would ask me to sell the stock when the price hit 15.5 yuan, making a modest profit of 100 yuan,” said Xu.

Zhou wasn’t greedy. She was satisfied with small profits.

“I always stay at home and have no other way to make money,” she said. “One hundred yuan could be used to buy some food.”

My mother loves the Oriental Pearl TV Tower, which is called Dongfang Mingzhu in Chinese. So she bought shares in Cangzhou Mingzhu and Guangdong Mingzhu, which she thought might be television towers in other places.

Zhou's son

Zhou is a bit philosophical about equity investment.

“Buying stocks is like buying ingredients to cook,” she said. “It’s normal for vegetable prices to go up and down. If there are several vendors selling the same vegetable, I’ll choose the one selling at the lowest price. It’s similar with the stock market. If a stock falls, I will buy some shares of it. If it falls more, I’ll buy more to make up the loss when the price rises a bit.”

She roughly estimates that she has made about 100,000 yuan in profit over the years from the stock market.

“The money has been used to buy an air-conditioner and new refrigerator, and to pay for my cataract surgery,” she said.

Her current portfolio includes some 10 stocks, including the Oriental Pearl TV Tower, Cangzhou Mingzhu, China State Shipbuilding, Guangdong Mingzhu, Shandong Gold and Lujiazui.

Her choices are sometimes based on pure nostalgia.

“My mother loves the Oriental Pearl TV Tower, which is called Dongfang Mingzhu in Chinese,” her son said. “So she bought shares in Cangzhou Mingzhu and Guangdong Mingzhu, which she thought might be television towers in other places.”

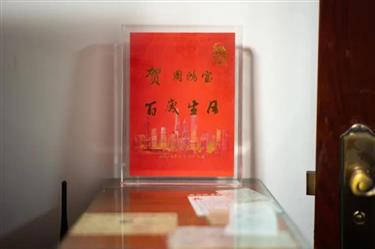

The certificate presented to Zhou by former Shanghai Mayor Ying Yong on her 100th birthday

All her stock trades are recorded in notebooks kept by Xu.

The centenarian’s account attracted the interest to her stock broker. At first, the securities firm couldn’t believe a woman that old was really investing in stocks and wondered if the account was somehow associated with money-laundering. Xu invited them to visit his mother.

When they went to her home, they found Zhou watching the stock market channel on TV and decided she was a bona fide investor.

“There are so many stocks on the market,” Zhou said. “But like relatives and friends, they may be many but only a few are close to you. I just stick with stocks I am more familiar with.”

Young investors pile into equities. Are they aware of risks?

Individuals comprise the largest bloc of traders on the Shanghai Stock Exchange, with younger investors flooding into the market after the SSE Composite Index posted nearly a 14 percent gain last year, despite the coronavirus pandemic.

In 2020, new individual investors in the Shanghai A-share market increased by 18 million to 178 million, according to China Securities Depository and Clearing. A report issued earlier this year showed people aged 24-30 accounted for nearly 30 percent of all investors in 2020.

Xu Kaidi, 19, head of the Stock Research Club at Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, is among the new breed of young investors.

After he graduated from high school in 2019, he invested about 10,000 yuan (US$1,533) in his stock account. In the past two years, his return on investment rose by more than 50 percent.

According to Xu, Shanghai has a good environment for stock investment.

“At a gym in the city, you may hear uncles and aunties discussing stocks, and it’s easy to join the conversation,” he said.

At the beginning, I made short-term investments but lost some money,” he said. “Then I switched to medium- or longer-term investments.

Xu Kaidi/Head of the Stock Research Club at Shanghai University of Finance and Economics

Xu now has about 100,000 yuan in his account. The shares he hold range over an array of segments: new energy, semiconductors, the military industry and liquor.

“At the beginning, I made short-term investments but lost some money,” he said. “Then I switched to medium- or longer-term investments.”

He said he watches for companies in transition that have profit potential. At the investment club, he helps schoolmates and friends who are newcomers to the stock market to learn the ropes.

Experience has taught him to be prudent. He said he thinks carefully before buying stock and does his research. After classes, he reads books on investment and stocks.

“I’ve signed up for a quantitative investment class, which will last for two to three weeks,” said Xu. “I also find books and other materials about it to read after school.”

Yu Haian and Tan Yili, a couple born in the 1990s, run an account on the video-sharing platform Bilibili to share their views and experience on investing, according to a CCTV report.

They have come to believe that realistic thinking is the only way to achieve stable returns.

“If you are positive about a stock, you should not trade it very often,” said Tan. “Instead, it will be better for you to hold it long term.”

Wang Dan, director of operations at Sinolink Securities, said that from last year, nearly half of investors opening accounts were born in the 1990s and 2000s.

“They have become a major group we pay attention to,” she said.

Wang said her firm provides fledgling investors training, including ways of spotting investment fraud, and professional advice.

Yang Zhongning, an investment advisor at Industrial Securities, said young investors are often drawn to companies involved in new products or technologies.

He advises them to experiment with various investment techniques to find the one that suits them best.

Besides stocks, many young people are eager to invest in funds that have shown profitable track records.

Xu told Shanghai Daily that many university students use their spare pocket money to invest in funds.

“It’s easy to buy funds,” he said. “Platforms like Alipay provide fund investment services. Compared with investing in stocks, funds have lower risk because a professional fund manager controls your account. And opening a stock account is harder than opening a fund account.”

However, like any market activity, there are always risks. When investment becomes a hot topic on social media, there a tendency for some people to follow along like sheep, without knowing what they are doing, he said.

“Investing in some funds can entail high risk,” Yu added.