Noted philosopher Li Zehou dies at 91, famed as an aesthetician with depth and style

Li Zehou

Noted philosopher Li Zehou died on Tuesday in Colorado, United States, at the age of 91.

To many Chinese Li is a household name, better known as an expert in aesthetics, with many looking up to him somewhat as a spiritual mentor during the "aesthetics fever" that caught on in the 1980s, the period often described as the Chinese enlightenment. As he once remarked, with ill-concealed pride, "In every student dormitory in the 1980s you could find a copy of my 'The Path of Beauty.'"

A native of Ningxiang, central China's Hunan Province, Li was born in 1930. He graduated in philosophy from Peking University in 1954 and began teaching at a university in Colorado in 1992, but returned to China frequently.

In a December 2009 interview, Li refuted allegations that he was promoting Confucianism in the US.

"I think it would take foreigners at least 50 to 100 years to really understand China," he said, adding that Western understanding of China is totally out of proportion with the Chinese intellectuals' understanding of the West.

Any Chinese intellectual, he said, could give the names of 20 foreigners impromptu, but not vice versa. "In Germany, except for sinologists, how many of them can come up with 20 Chinese names?"

"The Path of Beauty"

The situation is changing, though he insisted that it would take the West a long time to understand China from a cultural perspective.

"In the West, how many of them have read the 'Dream of the Red Mansions'? Well, they are not interested," Li said.

"As for my own books, it does not matter whether you read them or not. My books are for the future, and in the future foreigners would read them after all. Not now – it's too early yet," he observed.

A few years ago, Li became the first Chinese scholar to have his works included in the canonical "Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism."

Li's writings are full of critical clairvoyance, but also succinct, with a highly readable style.

His critically acclaimed "The Path of Beauty" has been popular among general readers since the 1980s, and according to a Sanlian Taofen Bookstore, it topped the store's best-selling book list for the year 2014.

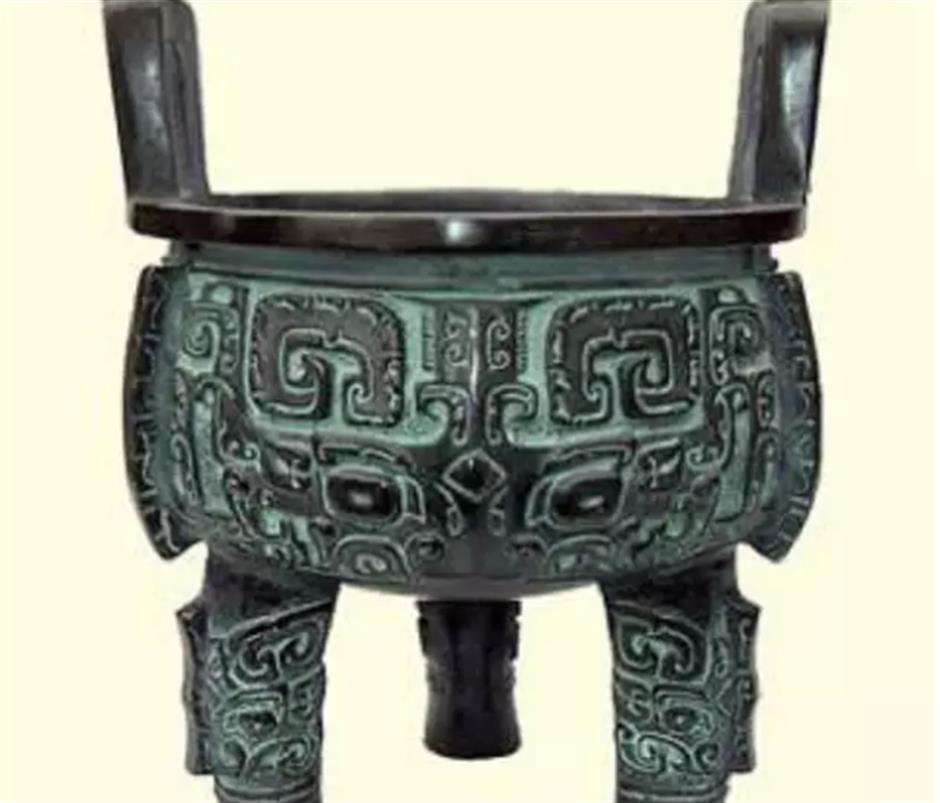

The book goes right into the fountainhead of Chinese civilization, beginning with the Chinese totems of the distant past, the "awe-inspiring" beauty of painted patterns on bronze ware, the divination of good and bad omens on oracle shells and bones in Yinxu, to the changing perception of beauty in the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

An ancient bronze ware decorated with taotie patterns

To Li, those ancient images wrought on bronze ware, uncouth as they seem to be, and fearsome, maintain an uncannily strong aesthetic appeal.

In discussing the mystically ferocious animal of taotie on bronze ware, Li observed and wrote: "In the mystique exuded by those august, formidable and fearsome images crystallized a powerful historical strength. When those mysterious, hoary images coincide with unstoppable historical momentum they become beautiful – sublimely."

He then compares the creepy feeling evoked by these images with the sense of foreboding suggested in a Greek tragedy.

Obviously Li owes some of his popularity to his ability to express himself with lucidity, brevity, and pace. The rhyming and flow in his writing comes from his familiarity with classical Chinese pianwen (prose written in the parallel style, with its stress on antithesis, and rhyme).

He was dismissive of the inaccessible, convoluted, and obfuscating academic papers he blamed on the influence of post-modernism in the West, saying that he himself hoped to benefit from English and American schools of philosophy free of their trivialities, over-niceties, and ornateness, and the depth and force of German philosophy without its inaccessibility.

And he expressed his firm faith in the Chinese style in the best term of the word.

Though Li confessed this was difficult, he was still aspiring to it.