The legacy of China's first female war correspondent

Zhang Yulian (1914-2010), the first female Chinese war correspondent

Sculptor Sun Yuli never really got to know his mother fully until he read a memoir left after her death. It turned out she was an extraordinary woman with stories to tell.

His mother, Zhang Yulian, was China's first female war correspondent. She died in 2010 at age 96.

In his memory, Sun remembers her as an intelligent and kind woman who has many friends and often makes Russian snacks. Her memoir, entitled "Bai Yun Fei Du," or "White Cloud Flying Over Waters," was published in 2015. An illustrated new version, with artwork by Wang Wanbin, was recently released.

Sun remembers her mom as an intelligent and kind woman.

"I really got to know my mom again after she passed away, not only from her memoir, but also from material related to her reporting and dug out by readers from all over China," Sun said. "I was often motivated to re-read the memoir again and again."

The book is divided into five volumes: The first four describes the author's legendary experience in chronological order; the fifth, entitled "Remembering Mom," is the author's memory of her own mother and her children's memories of her.

Sun, now based in Singapore, told Shanghai Daily via WeChat, "Many readers have also shared their own family stories about how ordinary grandparents, grand-uncles and other relatives answered the call to defend the country. Their paths may have crossed my mom's, and I often find myself in tears when reading their stories."

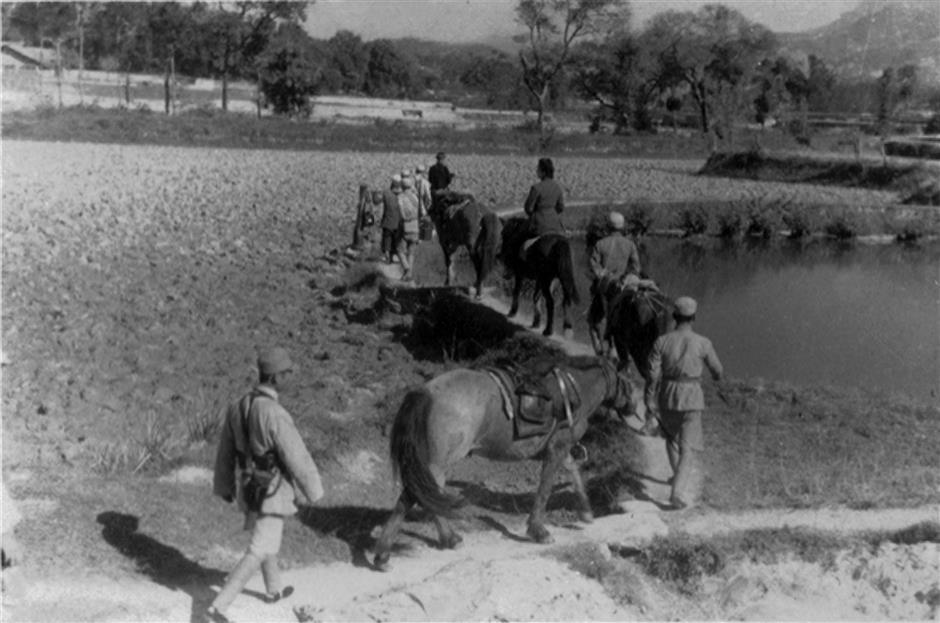

Zhang (on the horseback) was one among many ordinary people who answered the call to defend the country in their own ways.

In 1937 at age 23, Zhang was studying at Peking University when a Japanese invasion of China broke out at the Marco Polo Bridge, 15 kilometers southwest of Beijing.

Zhang fled south with crowds of people escaping the bloodshed and later joining former Soviet Union's Tass news agency in what is now a part of the city of Wuhan. She came well prepared for the job. She was fluent in Russian and had done some studies in journalism.

Zhang was sent to cover the Battle of Xuzhou in March 1938, where she joined other reporters who had to endure daily Japanese bombing as they followed the front line.

A Chinese brigadier she sought out for her first interview was surprised to see a female reporter and gifted her a Browning pistol for self-defense. The pistol accompanied her on many fronts across China for the next five years.

The young Zhang worked alongside many veteran war correspondents, including Soviet cinematographer Roman Lazarevich Karmen, with whom she visited the Communist forces' stronghold in Yan'an in May 1939.

Zhang and Karmen on the front line in Hunan, in November 1938. The Soviet director recorded over 10,000 meters of film in China, including interview with Chairman Mao.

"We have learned about the history of the era from textbooks, history books, novels, TV and movies," said illustrator Wang. "But her non-sensationalized, rational and very detailed descriptions of the front lines really impressed me. Those words bring that history to life and reveal the simple fact that any small wave in the river of history is a tsunami for those experiencing it."

Wang said she was drawn to Zhang's insightful stories when she read the memoir in 2015, shortly after it was first published. She was so impressed that she began drawing illustrations to accompany the stories.

The illustrated new version, with artwork by Wang, was recently published.

Zhang's unusual childhood forms the backdrop of her extraordinary life.

She was born in the northeastern Chinese city of Harbin in 1914, the year World War I broke out. It was also a time when China was undergoing dramatic social and political upheaval, with domestic warlords fighting for power and foreign influences penetrating the country.

Her parents nicknamed her Juju, which translates as "union," in the hope that the small family might weather turbulent times together. Unfortunately, it was not to be.

Illustration from the new book

Her mother died shortly after a younger brother was born, when Zhang was only 2 years old. The only picture she had of both her parents was later lost when she fled south from Japanese troops.

When her father took his wife's coffin back to his hometown for burial, he left Zhang with an affluent, childless Russian couple who lived on the same street. They gave her the Russian name Zoya, meaning "life," and she called them Wawa and Jiajia.

"In my heart, Wawa means mom, my dearest mom," Zhang wrote in her memoir. "She was the greatest mom, who raised me from age 2 to 19, when she passed away."

Sun Yuli is the second child of the family.

Illustrator Wang said she was especially impressed by how her adopted mother tried to give Zhang the best education possible in such turbulent times, insisting that she should learn Chinese and go to Chinese school to maintain her heritage.

"Thanks to that education, Zoya turned to such a great woman," Wang said. "Throughout the memoir, during all those difficult times, she never complains. Instead, she always strives to improve her knowledge and better herself. She had a simple patriotic heart."

Wang said she was inspired by Zhang's legacy to go back to university 10 years after graduation and earn a master's degree.

"I really admired that resilient, optimistic and constantly learning spirit of hers," she said. "Now, I have graduated with a master's degree from Xiamen University."

Inspired by that resilient, optimistic and constantly learning spirit of Zhang, illustrator Wang went back to university and earned a master's degree at Xiamen University.

Zhang returned to Peking University in 1942, when classes resumed in the southwest city of Chengdu. She had to sell the Browning pistol to pay for travel and tuition.

"I lived a poor life as a student in Chengdu," she recalled in the memoir. "But it was the happiest and most relaxed year in my life."

Her son Sun had only a vague notion about his mother's activities during the war and had to piece the puzzle of her life together after her death.

"My mom was an ordinary woman trying to survive in an extraordinary era of life and death, joy and sorrow, war and broken families," he said. "There were many ordinary people like her from that era ― the soldiers, the front-line nurses, the farmers. They all contributed in their own ways and made personal sacrifices. We Chinese always remember our history; it is a part of how we move forward."

Zhang and famed writer Xiao Hong in front of the office of Tass news agency in Chongqing on December 22, 1938.