Bright and bold, posters capture a colorful past

Yang Peiming holds up a calendar girl poster. These iconic posters comprise a large part in his museum collection.

China’s history can be told in posters — the bold billboards of images and slogans affixed to walls and other sites with social messages for the masses.

At the Shanghai Propaganda Poster Art Center on Huashan Road, visitors can view more than 6,000 posters, from the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 through its early days of opening up in the late 1970s.

The bright colors and striking images of the posters stand in contrast to the nondescript basement that houses the collection.

There are images of patriotic Chinese soldiers flying the national flag, hardworking farmers carrying hoes on their shoulders and raising their fists in defiance of capitalism. Chairman Mao Zedong appears prominently in posters, often surrounded by young Chinese holding up copies of the “little red book” of his quotations.

“The collection gives us a remarkable insight into China’s recent history,” says Yang Peiming, 72, the museum’s founder and owner. “The posters serve as valuable historical documents to remember different periods of the country.”

Yang lived through different periods from 1949, including the Great Leap Forward in the 1950s, the “cultural revolution” (1966-76) and China’s launch of the opening-up and reform in the late 1970s.

In 1968, after graduating in English at the East China Normal University in Shanghai, Yang joined thousands of other college students who answered the national call to go to the countryside to be educated by living and working there. He was assigned to Sichuan Province, where he worked in a cannery for eight years.

“The museum is not here to praise or criticize any period of history,” he says. “I am just simply trying to objectively trace the transformation of China through the art form of posters.”

The posters are arranged by timeline, which allows visitors to walk through the changes in the nation’s political, cultural and economic environment.

This early 1950s poster depicts the founding ceremony of the People's Republic of China, where Chairman Mao delivered a speech at Tian'anmen Square.

From 1949 to 1953, poster artists were encouraged to celebrate the birth of a New China. They show cheerful parades in front of Tian’anmen Square, the country’s founding ceremony and a happy wedding party where women were held up as equals.

In the mid-1950s, the focus of the posters changes to glorify industrial and agricultural production. In the late 1950s, they reflect the advent of movements like the establishment of rural communes.

Posters in the early 1960s turned to the theme of “fighting capitalism.” The soldier Lei Feng (1940-62) became an altruist icon familiar to all.

The 10-year “cultural revolution” witnessed a burst of poster-making. Chairman Mao is often depicted as a red sun, shining over the country. Educated young people hold up high the “little red book” as they board trains for the countryside.

Toward the mid-1970s, as the movement began to wane, poster appeared depicting more everyday scenes, like women buying stationery, children playing games and farmers bringing in the harvest.

With the end of the “cultural revolution,” poster themes turned to modernization. In one poster, a woman factory worker is depicted carrying a wheel gear and calling everyone to “strive for modernization.”

“Politics aside, the posters fostered many talented artists,” Yang says.

A poster promoting freedom in marriage

A poster promoting China's aviation science and technology

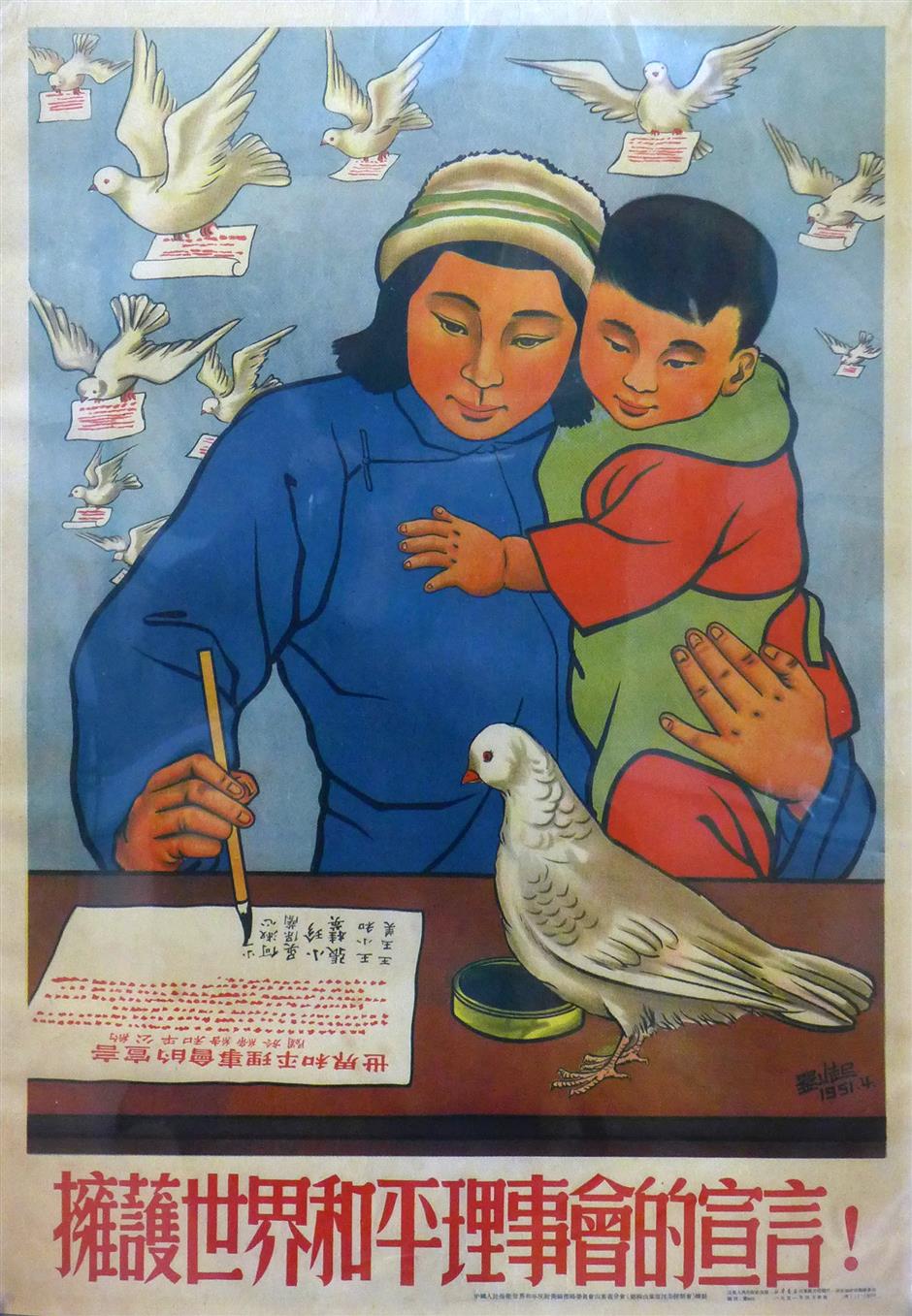

A poster featuring doves and a mother with her child calls for world peace.

Yang worked as a tourist guide for a travel agency in Shanghai after he returned from Sichuan. He started collecting posters during the 1990s, when no one realized their historical value.

He moved the museum to the basement more than 10 years ago, and the local government grants the site subsidies every year to support the operation, which partly covers the rent, he says.

Now in retirement, Yang says the museum runs well, supported by income from admission charges and gift shop sales.

He sells some posters from time to time to raise funds to purchase better examples from auction houses or private collectors, he says.

His collection spans an array of art genres, including oil painting, watercolors and woodcuts.

Gathering them together took decades of work. Many posters had been relegated to dusty storerooms or even found their way overseas. Some were purchased from auction houses. Many, of course, had been destroyed.

Yang says the value of a historic poster today is judged by its rarity, quality and distinctive message from a particular era.

Expats view the exhibits at the poster art center.

One of his most cherished posters depicts Chairman Mao standing tall in front of a crowd flying red flags. Mao, his hands clasped behind, is smiling and looking off into the distance.

Yang displays two different print copies of the poster. The slight difference lies in the size of the crowd.

“There is a story behind the two copies,” Yang says, as he carefully unfolded an original copy of one of the posters.

The two posters were actually painted by the same artist. When Jiang Qing, Mao’s wife, saw the first one, she was unhappy that the size of the crowd seemed to overshadow the chairman. She ordered another copy be done with a smaller crowd.

“I got the original of the first copy, but that of the second one was ruined,” Yang says.

He paid 250,000 yuan (US$39,000) for the original.

Yang is often on hand at the museum to discuss his collection with visitors. He is fluent in English and provides background information in English beside each of the posters.

If you go:

Address: Room BOC, 868 Huashan Rd

Opening hours: 10am-5pm

Admission: 25 yuan

Tel: 6211-1845

For more information, write to pmyang@sh163.net.